FALMOUTH — Late in the last century, my mother and I drove up to Waterville to hear Elie Wiesel. When we arrived at Colby College, where he was speaking, I realized that I’d forgotten to bring along a notebook that I used at various lectures. Shrugging, I thought: “It won’t matter just this once.”

I started across the parking lot, then stopped and returned to the old gray Camry. I reached in the glove compartment and took out a pen and a beaten-up 3-by-5 notebook kept for recording oil changes. We walked across the campus and found our seats in the rapidly filling auditorium.

What I remember of Wiesel is his slight stature, his calm, firm voice and his seemingly complete comfort with who he was in a world where everyone thought they knew him.

“That place (the SS graves at Bitburg, Germany), Mr. President, is not your place. Your place is with the victims of the SS,” he said during Ronald Reagan’s 1985 visit to a German war cemetery.

On the tiny pages of my notebook, I was able to catch jewels of Wiesel’s address. As a a little Jewish boy growing up in Romania, each day when he returned home from school, his mother asked him the same question. She did not ask him if he had learned his lessons well or earned good grades. She did not ask him if he had been a good boy and had made the teacher happy.

“Each day,” he said, “she always asked me if I had had a good question.”

And with this memory, he conveyed to me a truth about real education that my lifetime on both sides of the teacher’s desk had never explained with such clarity. From that point on, in almost every course I taught, that anecdote found its way into my curriculum.

He also told a tale from Jewish tradition – a story of the last rabbi at Sodom and Gomorrah.

Over and over, the rabbi spoke to his congregations on the error of their ways and the wrath of God that might result. After many years, his son asked: “Why do you keep preaching to these people? Can’t you see by now that you are never going to change them?”

The teacher replied to his son: “I don’t teach in order to change them; I teach so that they will not change me.”

“You can always tell the voice of the evil one,” Wiesel said. “It’s the voice that is whispering: ‘Go ahead and do it; it won’t matter.’ ” As I wrote down his words, I felt as though somehow his message had reached out to me in the parking lot an hour earlier.

Four years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, I was privileged to serve in the Peace Corps.

In the fall of 1994, I made the journey to the town of Oswiecim, the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps in what is now Poland. As I neared my destination, road signs heightened my sense of anticipation.

Finally, we rounded a curve and to my right I saw barbed-wire fences and red brick buildings.

At Auschwitz, inside the fences and through the gate with the words “Arbeit macht frei,” one of the buildings has been converted into a museum. On the ground floor the corridor is lined with official photos of the condemned, each a face, a name and an occupation.

I spent a long time studying those faces. And by the end I had made a discovery. The faces conveyed many emotions: anger, defiance, a kind of wistfulness, confusion and, in many, a sort of stunned blankness.

But none of the faces there – in that most heartless of all places – none of the faces showed fear, at least to my eyes, a half-century after the blinking of the shutter. It was as if the enormity of what each person, wrenched from whatever life had been, now recognized as reality removed the need to fear.

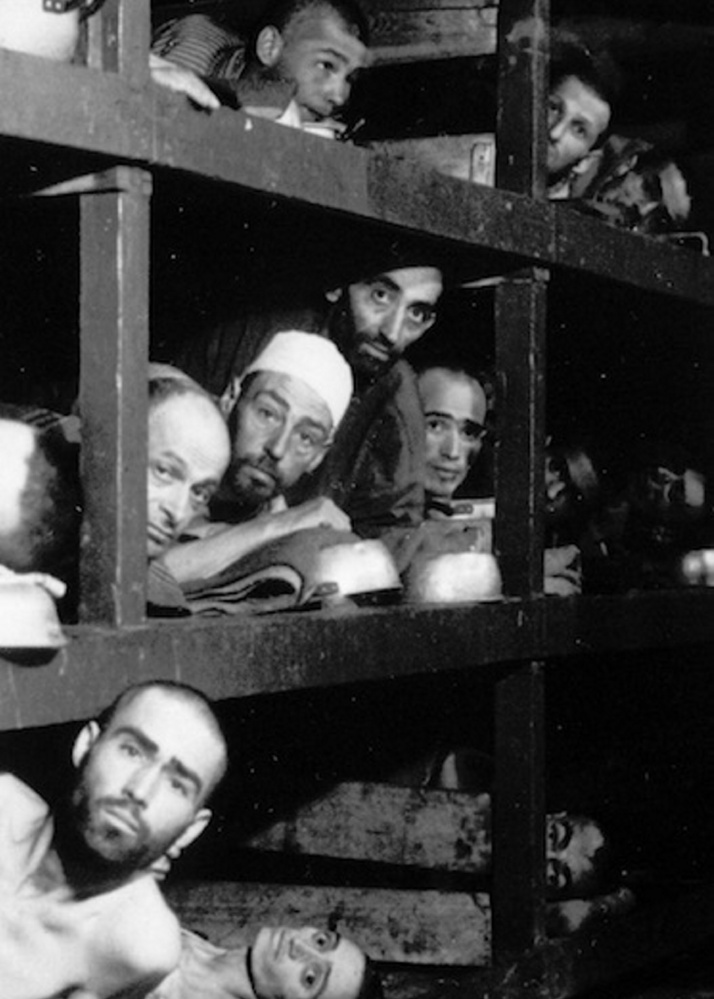

And in an official Army photo of four tiered bunk beds taken at the Buchenwald concentration camp at war’s end, there are a multitude of faces in various states of survival.

One, identified as Elie Wiesel, stares directly into the camera, unafraid, watching and remembering, so that we can all ask one good question and have the courage to act on its answer.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story