Some of my favorite parts of vacations are spent walking. Luckily, all over Maine, state and federal parks, as well as land trusts and nature preserves, offer trails up mountains, next to rivers, across fields and through forests.

You can enjoy these walks for the exercise, the beautiful views and the fresh air. But you may enjoy them even more if you know what you are looking at. That’s where a field guide comes in handy.

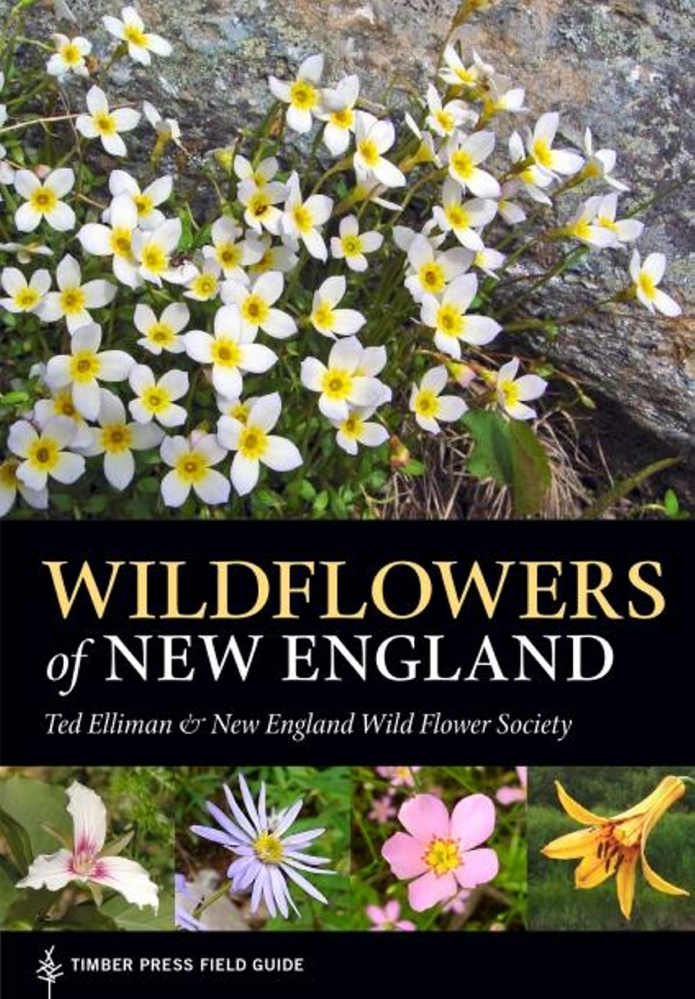

For flower lovers, “Wildflowers of New England,” written by Ted Elliman, a botanist and plant ecologist for the New England Wild Flower Society, and published earlier this year, is a great tool that can enhance your enjoyment of the outdoors.

It is based on “Flora Novae Angliae,” a much larger and more technical manual written by Maine resident Arthur Haines and published by the New England Wild Flower Society, a Massachusetts-based plant conservation organization.

“The point of my book is to present (the Haines book) to a more general audience,” Elliman said in a recent telephone interview. Elliman focuses on herbaceous plants and some small shrubs; he doesn’t include trees. As a point of comparison, the Haines book details 3,500 plants, while Elliman’s offers 1,100.

Elliman describes the plants in clear, concise language. Like his prose, the photographs offer clear close-ups that aid in identifying plants.

A six-part key also helps people identify plants in the field, namely color, shape, number of petals, type of leaf, arrangement of leaves and type of leaf margin or edge.

Drawings in the book illustrate various leaf shapes and margins. The plants are grouped by color, which appears on the page edges, making the book especially user friendly.

“It is a pretty easy key to use,” Elliman said. “Over the last couple of weeks I have been teaching some introductory courses, taking people out and using the book to identify flowers, and they are doing well.”

Say you’re out on a walk in late summer and you see the New England aster (but you don’t yet know its name). It’s a native wildflower – everywhere in Maine at that season – that for some reason the taxonomists now call symphyotrichum.

The flower is bluish-purple, so you would turn to the blue section of the book; purple is considered a subset of blue. You note that it has seven or more flower petals and the leaves are simple, growing alternately along the stem, with entire (or smooth) edges. So far, 12 flowers in “Wildflowers of New England” fit that description.

Now you’d check the pictures included with each plant against your specimen or look at plant height and other details to determine which of that dozen you have found. The descriptions also tell you what type of habitat suits each plant, another useful clue. (Identifying plants when the flowers are not in bloom will be more difficult.)

The guide includes any plants you might find in your walk in the woods in this region – even those that are sometimes deemed weeds and/or invasive. Non-native plants get asterisks next to their names; Elliman calls out the invasive plants.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some of the flowers included in “Wildflowers of New England” are quite rare, and he hopes to bring appreciation to them. But Elliman says he has purposely avoided ranking some plants as better than others.

From a practical standpoint, the book’s laminated cover and highly glossed pages will prevent damage if it’s raining out when you are in the field. Even if you never take the book outside, it’s worth reading the front sections, which are packed with good information on landscapes and natural and plant communities.

I asked Elliman if he, or other wildflower experts, keep a life list of plants they have seen in the wild the way avid birders do?

“There are many more plants than birds, so I think that keeping a plant list would be harder to do,” he said. “I don’t keep a checklist of what I’ve seen or what I haven’t. I think I might go crazy if I did that.”

Elliman reminds readers to look but don’t touch. Acadia National Park and most state parks prohibit digging up and picking wildflowers. Also, many such plants require specific habitats and won’t survive transplanting.

As he writes, “Take photographs, make sketches, observe and appreciate the plant, but leave the flowers, and the habitat, in the condition in which you found them. As the adage goes, plants grow by the inch but die by the foot.”

I’m sure my own copy of “Wildflowers of New England” will get some good use when I go fishing this summer. If I don’t catch any fish – often the case – at least I’ll have the satisfaction of identifying a few new wildflowers.

TOM ATWELL has been writing the Maine Gardener column since 2004. He is a freelance writer gardening in Cape Elizabeth and can be contacted at 767-2297 or at tomatwell@me.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story