GEORGETOWN — Rituals form part and parcel of the human condition: patterned, special, yet regularly repeated exercises bringing people together to celebrate some shared value.

They can be centered on national identity, like the Fourth of July; religious commitment, in the form of Sunday church service; or ethnic solidarity with holidays like Kwanzaa. Adherence to rituals tells us what we believe is most important.

This is not the same, it must be noted, as what we say is most important. Think, for example, of a minister who would dare to schedule a Sunday service that conflicted with the Super Bowl. She would soon discover what her congregants really valued.

As social and temporal beings who desire continuity in spite of change, humans need rituals. They help keep us from splitting apart into totally separate realms – little islands of “solitarity,” we might say.

A successful ritual brings together people who, though they might differ in many respects, share in some concern, some value and thus express and live out, not solitarity, but solidarity. A pilgrimage to Mecca becomes an exercise in transnational, multi-ethnic, multi-racial solidarity. A Sunday church service can bring together a bank president and a building janitor.

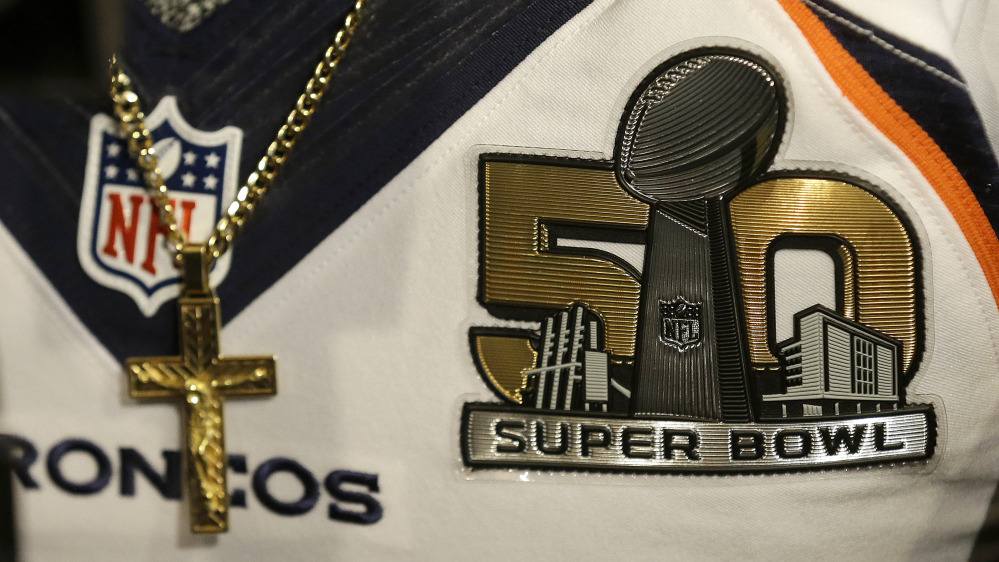

In the United States, no ritual is as important as Super Bowl Sunday. Getting something like 115 million people to converge on a single event is quite a feat. Like many rituals (think Thanksgiving meals, Fourth of July picnics, Jewish Seder), this one is associated with food. If ritual is about solidarity, then there is hardly a better way to symbolize it than by having people gather to share in nature’s bounty.

It’s good if the food has symbolic meaning; even better if the same foods show up in diverse geographical locations (hot dogs on the Fourth of July in Seattle and in Miami); and better still, on the household level, if there are common platters in which the friends share (think a central container loaded with salsa). Together, all of this allows for positive solidarity based on common interests.

So far, so good. What else is happening with this most prominent of American rituals? Well, what has already happened with Sundays, once associated with Christian rituals, now taken over by commerce and sports. What we consider to be our highest goods are always revealed by what we do, not what we say. Think again of the minister who would schedule a religious service opposite the super bowl, or even opposite a regular Sunday game.

The greatness of an event like Super Bowl Sunday is how it does the work of a typical ritual: suspend normal activities, gather people together, celebrate and, by being focused on a single event, express solidarity with a diverse group of individuals.

At the same time, rituals are associated with ideals. In this sense, the Super Bowl allows us to recognize what we consider to be of such importance that just about an entire country comes to a halt. Democracy, its critics repeat over and over, carries with it an inherent flaw: a tendency toward leveling and flattening, a penchant for heading toward the lowest common denominator.

In a country with various and conflicting cultural, religious and moral ideals, achieving solidarity – especially the sort not occasioned by a common enemy identified in war – often depends on finding some lowest common denominators. Spectacle sports and commerce, the two main ingredients of the Super Bowl, offer just those common denominators.

Both offer straightforward, streamlined criteria for what is “best,” i.e., the highest ethical value. In one case, it is victory in a championship game, in the other, it is success marked by wealth. More old-fashioned ideals for determining what is “best,” such as those derived from cultural, political and religious traditions, kind of take a back seat. They typically emphasize quality over quantity, do not divide people into winners and losers and offer other criteria besides material accumulation as a sign of goodness.

Solidarity is good, rituals are crucial to human life, ideals are present in our practices. Super Bowl Sunday offers an opportunity to think about which ideals we celebrate and which we have left behind.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story