American Moderns” showcases masterworks on paper from the Wadsworth Atheneum. Highlights of a great collection, the 90 works on view in the Portland Museum of Art are strong ambassadors.

The exhibition is both exciting and easy to digest. While the accompanying catalog would have you think it self-divides into polemical and divisive groups, the works themselves reflect and reference each other more as friends than firebrands.

While the entire show is strong, there are a few standouts, headed by Andrew Wyeth’s 1956 masterpiece “Granddaughter.” In front of the gray wood of a well-weathered wall, a young black girl is shown in profile standing at crisp but distracted attention. Her eyes drop and turn away from her grandfather, who leans over his cane or tool — his face completely obscured by an old broad-rimmed hat. His hands reveal him: They are knotted but strong, and their long nails tell us his days of hardest toil are over. The personal narrative is a compelling mystery.

Wyeth’s textures and coherently-lit details are unusual in any medium (including photography), so seeing them in a watercolor is startling. Wyeth puts us close enough that what we see are the details we would see if standing there. The girl’s face and hair include some of the best painting I have ever seen.

The show’s other masterpiece is Edward Hopper’s 1927 watercolor “Captain Strout’s House, Portland Head,” an iconic image of the handsome cottage at Maine’s oldest lighthouse.

Hopper is well represented in this exhibition by six excellent works. The most complex, “Rockland Harbor,” depicts the town’s industrial warehouses, working piers and commercial buildings with Hopper’s wholesome sense of sunlit architectural volume. It is an intricate but highly successful composition.

The exhibition’s most unusual Hopper is his 1930 watercolor “Truro Station Coal Box.” Below a light-blue sky and balanced by the stationhouse’s edge on the image’s right, we see a landscape in four bands of color, treeless and only broken by a geometrically simple coal box. The bands feel like successive theatrical stages, one visually behind the next — spatial but highly abstract. It is an odd yet brilliant composition, and possibly the sparest of Hopper’s career.

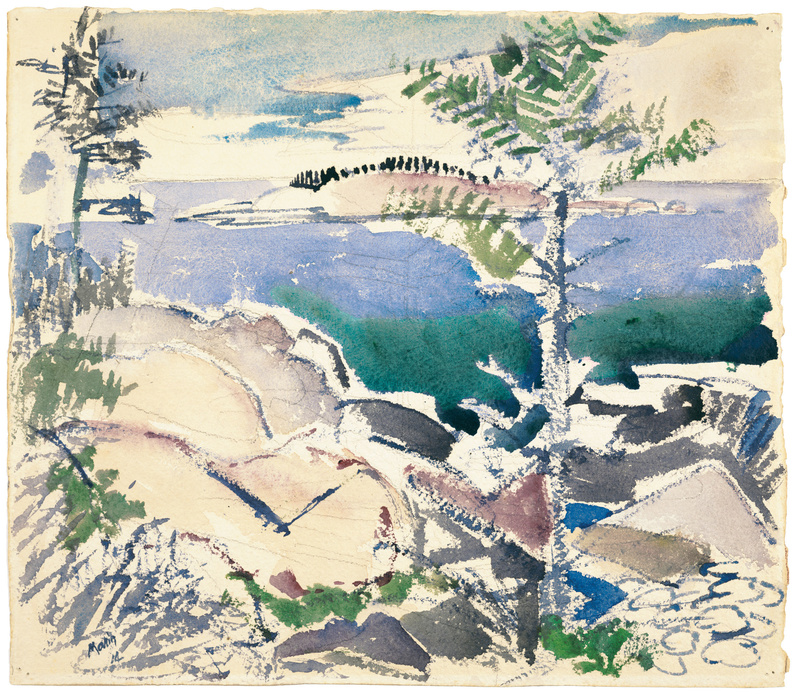

John Marin’s five terrific watercolors greet everyone entering the exhibition. Marin’s three New York City works are dazzling and sophisticated despite their jumbled frenzies, but I prefer his two seascapes, in which his jazzy rhythms exude palpable boldness rather than the quivering chaos of the city. His 1914 “Big Wood Island” shows an island crested with dotted trees. Your vantage is the rocky shore, the edge of which seems to crash into the surf. The whole scene shifts with the ebb and flow of the wisp and weight of its forms.

I adore Marin’s 1941 “Green Sea, Cape Split, Maine.” The shore is just a few large, black rocks at the edge of a swirling and flowing green ocean. A few streaks of cloud are enough for a sky over the ocean’s frothy green dance celebrating the wordless jubilance of nature.

There are too many excellent works to list. Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s grapes and flowers are delicious. Ellsworth Kelly’s simple green “Corn” commands the cover of the catalog for good reason. Georgia O’Keeffe’s sideways clamshell is my favorite painting by the artist. There are strong surrealist works by Yves Tanguy and Salvador Dali. Ben Shahn’s vacant lot is a monument to empty urban space and loneliness. Paul Cadmus’s black-ground pastel peering into an office skyscraper at night is exquisite. Charles Demuth’s still lifes are gorgeously light. Rockwell Kent’s “Moby-Dick” illustrations are brilliant. Milton Avery’s “Church by the Sea” is Avery at his very best. And so on.

I think the large Burchfield landscapes are depressingly dreary, and that Gaston Lachaise’s creepy male nude is the worst combination of Herculean and hermaphroditic. So there are works I don’t like — but not many.

Especially if you can do it in one day, I strongly suggest seeing “American Moderns,” the PMA’s new Homer installation (more on that soon) and the two shows at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, “Learning to Paint” and “Methods for Modernism.” Together, these four present a sparkling overview of how 19th-century American painters moved from a European mode of painting into 20th-century modernism.

And they just might change your understanding of art in America.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story