Nicole Maines never set out to be a voice for transgender youth.

“If you asked me 10 years ago if this is where I’d be, sitting in my dorm room watching myself on ‘Good Morning America’ and talking to a reporter, I’d say that’s crazy,” she said.

In her early years, Nicole didn’t have much of a voice at all, at least publicly. Her parents, Wayne and Kelly, fiercely protected both her and her brother, Jonas, from public attention.

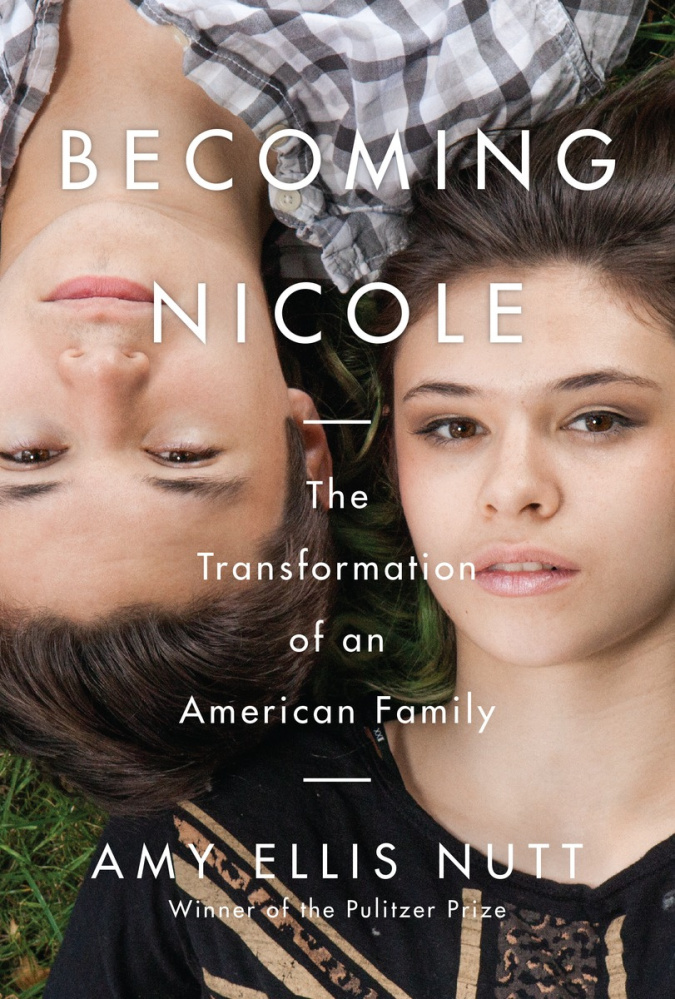

However, the publication this week of “Becoming Nicole,” a book that lays bare her struggle of growing up transgender – a story made unique by the fact that Nicole is one-half of a set of identical twins – and how the experience ultimately transformed the entire Maines family, has changed that.

The Maineses, who live in Portland, have been fielding interview requests from across the country, ranging from national morning news shows to People magazine, in anticipation of the book’s release Tuesday. They are slowly growing into their role as spokespeople for the transgender community.

“This wasn’t something we did lightly,” Wayne said. “But it took 10 years for me to understand what was going on with my daughter. If we have to wait 10 more years for others to come around, a lot of kids are going to end up in harm’s way.”

Wayne and Kelly knew early on that although their children were biologically identical, they were different. Nicole, born Wyatt, was always interested in girl things and from an early age asked when she was going to become a girl. After years spent fighting the inevitable, the parents decided to let her live as a girl and legally changed her name.

Kelly was supportive from the beginning, but said there was never a road map.

“I had no idea if I was doing the right thing,” she said. “I hoped and I surrounded myself with people who could help, but we were all feeling our way blindly through this.”

It wasn’t easy. Nicole endured bullying from classmates and discrimination from officials in the Orono School District, an ordeal that culminated in a landmark court case that affirmed the right of transgender students to use the bathroom appropriate to the gender with which they identify.

It wasn’t until the family moved south to Portland, enrolled their children in private school and Nicole began hormone treatment that their lives started to resemble normalcy.

Written by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Amy Ellis Nutt, “Becoming Nicole” explores not only the Maineses’ story but also the science of gender and how research and understanding of those issues have evolved and continue to evolve. The story is unique because Nicole is an identical twin and her transition essentially undercuts the theory that a child’s identity is nurtured.

Although she has been living as a female since elementary school and underwent gender reassignment surgery in July, Nicole said it was tempting to go off to college someplace where people wouldn’t know she was born a boy, to never have to share that.

“I’ve thought about that a couple times,” she said. “But I think that it’s part of who I am. And when you’re presented an opportunity to represent a group of people who need representation, it’s not so much an obligation but I feel like it’s a calling. And if you have that opportunity, you should take it.”

•••••

Wayne and Kelly Maines, unable to have children of their own, adopted twin boys from a relative of Kelly’s in 1997. They named them Wyatt and Jonas.

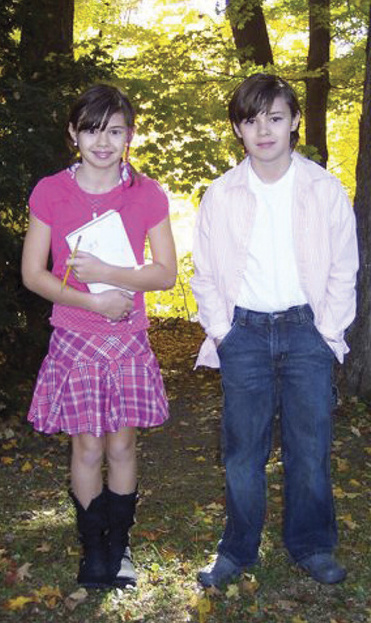

Although the twins were identical and raised in the same environment, the differences in their personalities were evident early.

In an early scene in the book, Wayne is pointing a video camera at a 2-year-old Wyatt, who is wearing a skirt and dancing in front of the stove – the glass reflecting his moves. Wayne asks to see the boy’s muscles and, after ignoring his dad several times, Wyatt relents but isn’t happy about it. Wayne, too, is disappointed.

There is another scene in the bathroom where Wyatt, almost 3 years old, tells his father that he hates his penis. Wayne pulls his son in for a hug, and says, “Everything’s going to be okay,” unsure if that would turn out to be true.

Not long after moving to Orono, the Maineses threw a house party. Guests were downstairs but the kids were nowhere to be found. When Wayne went looking, he found Wyatt at the top of the stairs, dressed proudly in a pink princess dress. The child would be entering first grade soon.

“Wyatt, you can’t wear that,” Wayne said, loud enough for the party guests to hear, aware of the uncomfortable questions that his son’s outfit might prompt.

Wyatt froze and then started to cry.

Kelly said she always knew Wyatt was different and when it became clear that he should live as a girl, she did everything she could to make that process easier. Wayne, by contrast, retreated into himself, unable to process what was happening.

His acceptance came gradually. At a school concert when Nicole was in fourth grade, she dressed more like a girl publicly than she had before. Wayne gave her a bouquet of roses. Two years later, Wayne took Nicole to a father-daughter dance.

•••••

Kelly and Wayne Maines sat down for an interview late last week at their home in Portland’s Deering Highlands neighborhood. Nicole and Jonas participated in the interview by video from Orono and Farmington, respectively, where they are in college.

Jonas, who has always been close to his twin, said he was never bothered that his brother identified as a girl. That’s just the way it was. But as they grew older, Wyatt’s transition to Nicole did relegate Jonas to the background.

“There was a lot of attention and focus on her growing up. I’d be lying if I said there weren’t instances where I thought, ‘What about me?’ ” said Jonas, who is studying psychology and theater at the University of Maine at Farmington. “But I never felt forgotten.”

When the Maines finally relented in middle school and let Nicole live as a girl, the change presented challenges at school. Which bathroom would she use?

At first, school officials allowed Nicole to use the girls’ bathroom. However, after the grandparent and guardian of one of her classmates complained, administrators told her to use the staff bathroom instead. Later, on a camping trip with her class, the school told the family that Nicole would have to sleep in a tent with a guardian instead of in a tent designated for girls.

The bathroom issue became a pivotal moment in the Maineses’ lives.

The family filed a complaint with the Maine Human Rights Commission, which found that the school had discriminated against Nicole. That paved the way for a lawsuit, which was rejected by a Superior Court judge in 2012 but then overturned by the Maine Supreme Judicial Court less than two years later.

That January 2014 ruling was the first time a court in the United States had ruled that it is unlawful to force a transgender child to use the school bathroom designated for the sex he or she was born with rather than the one with which the child identifies.

Nicole Maines’ court case was a landmark ruling for transgender rights, but the fight is far from over. In states across the country, transgender individuals still face discrimination. Just last week in Chicago, a school district announced that it would not allow transgender students to use communal locker rooms – a decision that will almost certainly be challenged.

“With civil rights, I feel like it’s something that you’re never really not fighting for,” Nicole said. “We still talk about race. So, even when we get certain rights we’ve been fighting for, I think there will always be a discussion.”

•••••

Before the Maine supreme court ruling came down, the Maines family had already moved from Orono to Portland. They needed a fresh start, although Wayne still spent weekdays in Orono to keep his job at the University of Maine.

When the twins were enrolled at King Middle School, Wayne and Kelly thought it was best to introduce Nicole as a girl. Only top school officials would know she was transgender.

It proved to be a difficult time for the family, especially Nicole.

“It was really uncomfortable. I didn’t feel like I was being honest,” she said. “It was like I was only being part of Nicole. I was never able to say there is this part of me and that’s OK.”

Jonas and Nicole never really fit in at King. There were always whispers. Jonas even got into a fight because of them.

When it was time for the twins to enter high school, the Maineses chose Waynflete, a private school that would further strain the family’s finances, already stretched thin from maintaining two households.

In the end, it was worth it. Nicole had room to be herself. She acted in school plays and volunteered for the state’s successful campaign to legalize same-sex marriage. Jonas found his stride, too, joining the Model United Nations and mock trial teams, and grew proficient enough on the guitar to perform at open mic nights.

Nicole had been undergoing hormone treatment, first to suppress puberty and then develop breasts, for some time at Children’s Hospital in Boston, which has a renowned program for people with gender dysphoria. By her senior year, she was preparing for sex reassignment surgery, the final step in her transition.

Shortly before the surgery on July 28, Nicole said she thought about Wyatt, something she hadn’t really done in years.

“There was a long time when I wasn’t comfortable with Wyatt or that name because it felt like that was a reminder of a time when I wasn’t comfortable with myself … and I really didn’t want to go back there,” she said. “But recently, I’ve really accepted that Wyatt was a part of me.”

Kelly said Wyatt was “just a name.”

“I picked the name, I miss that name, but the person is still here,” she said. “I just told (Nicole) that if she ever has a son she has to name him Wyatt.”

Nutt said although the book details Nicole’s journey, the story doesn’t belong to any one family member. Each is unique. Kelly, the author said, is the “real hero” of the book. Jonas, perhaps, is the most sensitive family member and unfailingly supportive of Nicole. Wayne undergoes the biggest change.

“I think he reached that point where he recognized he was late to the game,” Nutt said of Wayne. “It really enabled him to share his transformation. And he’s proud of it.”

•••••

The book’s release could not have come at a better time, Nutt said. Transgender rights have gained national attention, in part through high-profile individuals who have come out as transgender, like Caitlyn Jenner, the Olympian-turned-reality TV star who transitioned this year, and Laverne Cox, a male-to-female transgender actress who starred on the Netflix original series “Orange is the New Black.”

Nicole, who aspires to be an actress, maybe, recently got a role as a transgender teen on “Royal Pains,” a medical drama on the USA network.

She’s been honored numerous times already for her advocacy, including by Glamour magazine last year. She is set to receive an award from the Matthew Shepard Foundation, an LGBT rights advocacy organization.

Nicole said she’s embracing her celebrity. She knows it will likely only increase with the release of the book, but she’s OK with that.

“I think it’s nice to finally be able to have a voice,” she said. “When everyone is talking about you and talking around you, it’s hard when you feel like you don’t have a say in your own life. I am relieved to be able to advocate for myself. I mean, you know yourself best.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story