Pity the poor almond. It’s had a rough couple years. Vegetarians may be basking in the glow of almond milk’s rising star, but the healthful nuts have been roasted by the media during the ongoing water crisis in California.

Turns out, they’re not the “devil nut” Gizmodo so famously (and facetiously) called them.

The bad press for almonds got rolling last year with a Mother Jones story titled “Your Almond Habit is Sucking California Dry.” The left-leaning magazine has since followed up with a series of almond-bashing stories, including “Lay Off the Almond Milk, You Ignorant Hipsters,” and “Invasion of the Hedge-Fund Almonds.”

Other news outlets piled on, with an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Stop Water Abuse by the Almond and Pistachio Empire” and a piece on National Public Radio titled “California Drought Has Wild Salmon Competing With Almonds for Water.”

But as the drought grinds on in California, the reporting on the issue is improving, according to Heather Cooley, who heads the water program at the Oakland, California, think tank Pacific Institute.

“There’s been a lot of sensationalism and looking at one or two crops, rather than the whole picture,” Cooley said. “Now we’re having a much more informed conversation about agricultural water use.”

By late summer, the news media had backed off, with The Los Angeles Times reporting: “Almonds are no longer villains – or scapegoats – of the drought.”

Still, in my reading, little of the reporting in major media outlets examines California’s true top water user with the same level of scrutiny brought to bear on almonds. While almonds and their water use make headlines, the state’s most thirsty industry rarely merits a mention.

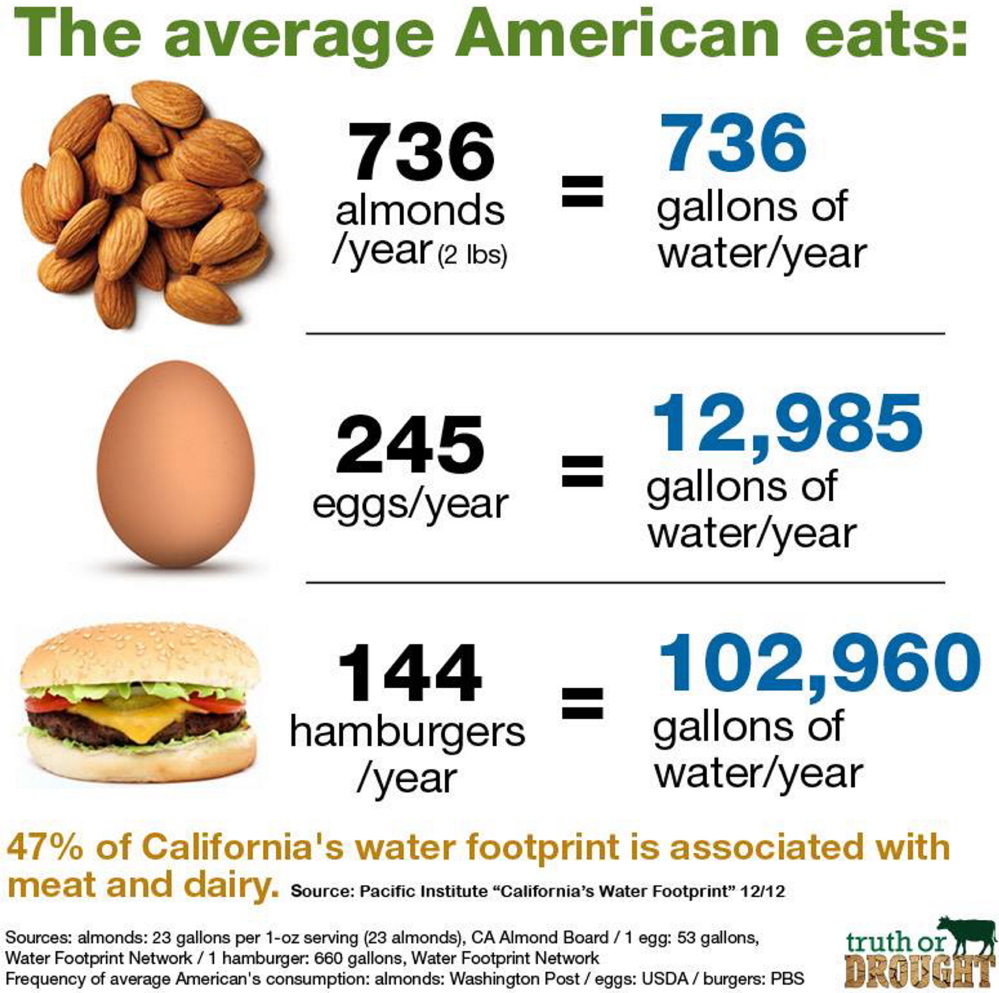

According to the Pacific Institute’s 2012 report “California’s Water Footprint,” more than 80 percent of the water used by the state goes to agriculture; of that, a whopping 47 percent is used to produce meat and dairy products.

“The higher you go up the food chain, the more inefficient it become in terms of calories and water,” Cooley said.

Such figures aren’t unique to California. Three years ago, the prestigious Stockholm International Water Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, issued a report which warned that unless humans cut their consumption of animal-based foods to 5 percent or fewer of calories, we will face catastrophic water and food shortages by 2050.

The report notes that when water and food run short, the world’s poor are hit the hardest by food insecurity, malnutrition and famine. With one billion humans currently malnourished, according to the report, population growth, changing climate and drought will only increase the demands on the planet’s limited fresh water supply.

“Producing animal calories requires a lot of water, generally much more than vegetal calories,” Jan Lundqvist, one of the report’s authors, told me via email. “This is not because animals drink a lot of water, but primarily because feed has to be given to animals, generally over long periods and sometimes many years.”

This past August during the annual World Water Week conference organized by the Stockholm International Water Institute, the idea of “Going Vegan” beat out a host of other water-saving strategies to win the event’s Best Water Ideas campaign.

The material in support of the campaign noted: “It requires 15,500 litres of water to produce 1 kg beef; this can be contrasted to 180 litres for 1 kg tomatoes and 250 litres for 1 kg potatoes … If more consumers changed to less water-intense diets and chose, for example, pulses (dried beans from the legume family), vegetables and grains over meat, a lot of water could be saved.”

Using the same numbers from the Water Footprint Network, we learn it takes 8,047 liters of water to produce 1 kilogram of almonds. Like all fruit and nut trees, almonds need water year-round, Cooley said, whereas vegetable crops, such as tomatoes and potatoes, require water only for the few months they’re in the ground. The crop that uses the most water is alfalfa grown for dairy cows.

While almonds and other tree nuts do use a lot of water, and a booming almond market has pushed orchards to expand into unsuitable land, there’s no denying meat uses more water – almost double what almonds require, based on the numbers from the Water Footprint Network.

So why do reporters criticize almonds while routinely ignoring the link between meat and water use?

“The dots simply aren’t being connected by the public due to a collective pro-meat bias,” said Lorelei Plotczyk, founder of the California-based grassroots organization Truth or Drought. “Our goal is to help connect those dots.”

Truth or Drought recently launched a “Save Water, Eat Plants!” campaign complete with lawn signs, leaflets and window decals in veg-friendly restaurants.

“We basically could not design a better way to waste astounding amounts of water and crops than to cycle them through animals first,” Plotczyk said.

One statistic Plotczyk likes to share comes from National Geographic, which says a vegan diet saves an average of 600 gallons of water each day compared to a meat-based diet.

While California’s water policy doesn’t address the water-intensive needs of the meat industry, there are signs that awareness is spreading in the political arena. In June, California Gov. Jerry Brown responded to a question about meat eating and the drought by saying, “If you ask me, you should be eating veggie burgers.”

Still, too few ordinary Americans have made this connection between meat consumption, water shortages and hunger.

Lundqvist at the Stockholm International Water Institute said our own food security blinds us to the struggle billions face in finding food each day. “Food shortages hit the poor and those who are denied access to the food produced,” Lundqvist said. “For us who have money in our pockets, it is a different world.”

It’s also a world where people bash almonds but fail to spot the real water guzzler: a meat-heavy diet.

Avery Yale Kamila is a freelance food writer who lives in Portland. She can be reached at:

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter: AveryYaleKamila

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story