To anyone who claims that all the great wine regions of Europe have been discovered, that wealthy speculators have stolen our future, that individuality has been wiped out by globalization, that affordable age-worthy red wines are no longer available, there is a withering response: Portugal.

Portuguese winemaking culture is probably the most traditional, unglobalized in the world; Georgia is the only possible competitor that comes to mind. Some “international varietals,” such as cabernet sauvignon and syrah, have made inroads, but not overwhelmingly; I don’t expect a ratings-hungry “Super Douro” style to develop any time soon. For a number of reasons, the native grape varieties still rule, and the country’s north-south orientation and Atlantic-facing aspect play host to many soil types and micro-climates.

Small-scale production reigns as well, with an eye toward preserving unique tastes rather than bending to market whims. This isn’t due entirely to high mindedness. It reflects, in part, dismal financial reality: The nation’s economy is weak,. There is no money to create slick international marketing campaigns (think Austria). The result is an established, classic group of wine regions with little choice but to soldier on in the ways they always have.

So: a relatively inexpensive, time-honored, somewhat strange and off-radar set of wines that can go either big-fruit or high-mineral (or both simultaneously). To a curious American wine drinker or aspiring sommelier looking for a scoop, what could be more enticing?

MANY NATIVE VARIETIES

American wine enthusiasts searching for a relatively untrammeled field of inquiry, for wines of distinctive character rooted in place, for bottles to easily grace weeknight tables as well as grow into prized treasures in a cellar, for vinous tickets to history and place, for direct connection with small-scale winemaking, ought to pay more attention to Portuguese wines.

This will be difficult at first. The language is an obstacle, since few of us studied Portuguese in school. Neither tourism nor a romantic yearning for simpler lifestyles have put Portugal center stage for Americans. The country does not yet have its Peter Mayle or Frances Mayes or Elizabeth Gilbert. And while there are small Portuguese immigrant communities in the United States, they are rather self-contained and have not produced a noteworthy restaurant culture.

The single greatest challenge Portuguese wines present to comprehension, though, is also their greatest asset when drunk: the many native grape varieties, which are usually blended for the most noteworthy reds and whites. (Today’s column will focus on red wines, though I have written previously about Portuguese whites and will again soon.) The Big Three red wine grapes are touriga nacional, touriga franca and tinto roriz (tempranillo in Spain). The tourigas are best known as the foundation for the great ports of the Douro, though they are the primary components of an increasing number of dry wines from not only Douro, but Dão and other regions as well.

Beyond those three grapes, there are many other fascinating varietals. My favorite, the tannic and somewhat wild-natured baga, which leads the way in wines from the Bairrada region, comes across as a sort of Portuguese nebbiolo: broad, structured and bold when young, but clearly signaling development into delicacy and nuance as it ages. Castelão, trincadeira, bastardo and souzão make interesting appearances in many wines, and the red-fleshed alicante bouschet is a big-hearted, grand sort of grape.

The permutations are dizzying, for in addition to the many different blending ratios among so many distinct varietals, the various regions of Portugal are home to an enormous diversity of soils and geological substructures: granite and schist in Douro and Dão; limestone, clay and sand farther west in Bairrada and other coastal areas; more schist to the southeast in Alentejo. Western vineyards take the effects of the Atlantic ocean, while southern and eastern regions are tempered more by the Mediterranean climate.

YOUNGER VINTNERS TUNED IN

Vinification runs the gamut. Barrel use can be heavy-handed and even clumsy, especially since so much of the approach to winemaking is rooted in the traditions of port. The cheaper dry wines for which Portugal has more recently become known often betray over-reliance on new oak, leading to lipstick-on-a-pig extreme makeovers on top of rustic winemaking. A younger generation of vintners, however, more tuned in to the international trends toward lighter-handed production methods that promote freshness and clarity, has used better temperature control in the cellar, and dialed back the rote deployment of wood.

The combination of unique features from the grapes and attempts to merge traditional technique with contemporary understanding thrills me, but there’s a risk. I do not want to colonize Portugal.

“There is so much new and exotic territory for me to explore!” I exult, echoing sentiments voiced centuries ago by “discoverers” of a New World that had already been inhabited for millennia. I bring a novice’s wide-eyed ignorance to the country’s wines. Can I, in finding out more about them, avoid simplifying and pacifying? Can I come to love and understand the distinctiveness of Portuguese wine culture without seeking to tame it? Can we all support its traditions without imposing our own? An open attitude while drinking may help us toward some useful answers.

The Douro was long ago established as Portugal’s pre-eminent region through the production of port. Its great dry wines can be intense and broad, but the Vega Douro 2011 ($13) is a more approachable exception. Produced from the three classic grapes of the region, it presents like a joven, or young wine, from Ribera del Duero, or even a Beaujolais, with pale red fruits, dried flowers and a raspy texture.

A different sort of Douro expression, with greater depth of flavor if less delicacy, and an overall sweet-fruited character, is the Portal Colheita 2011 ($17). A higher proportion of tinto roriz (tempranillo) leads to ripe flavors, more akin to Argentine malbec. Fans of a more classic, old-school orientation in the Douro ought look to Quinta do Crasto. Their Douro Tinto 2012 ($16) is even-keeled, tarry and rich. The Reserve Douro Tinto 2011 ($40) is exceptionally complex, explosively mineral; comparisons are dangerously inaccurate, but fans and collectors of Left-Bank Bordeaux and traditionally made Rioja can save a lot of money here.

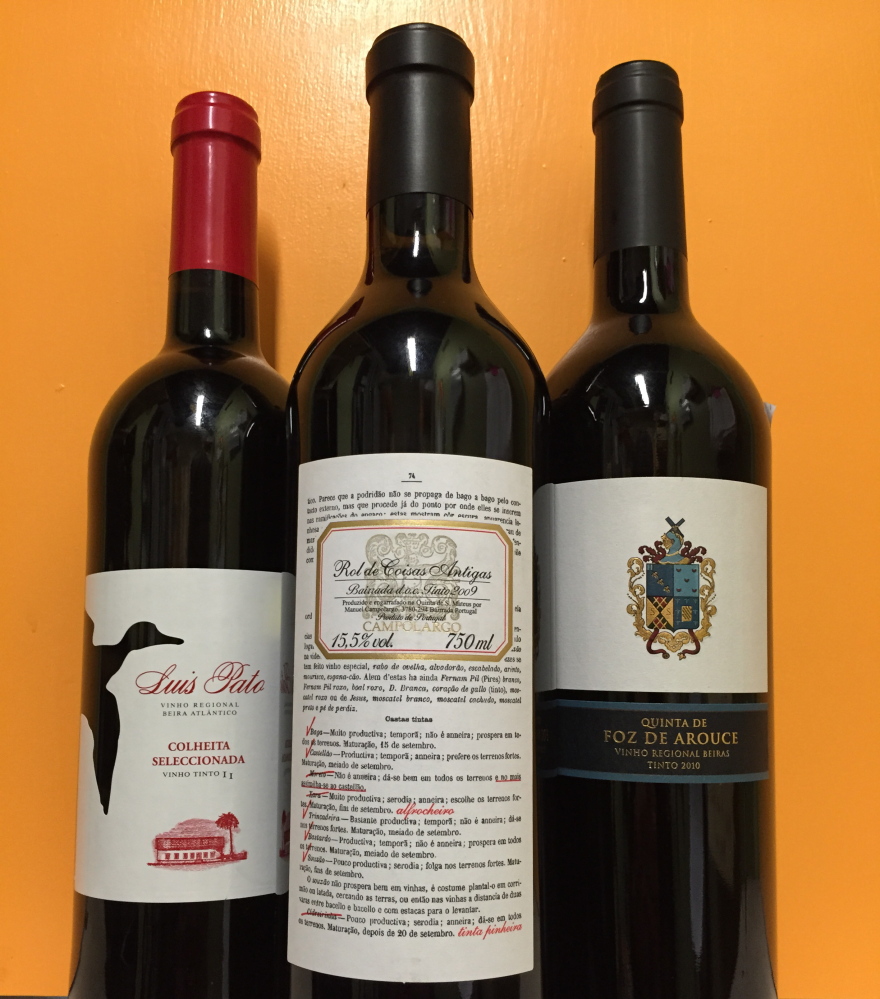

Bairrada and Beiras, the regions closer to the Atlantic, a bit farther south and west of the Douro, have fewer analogies to the French or Spanish styles with which most of us are more familiar. But that’s their strength. The Quinta de Foz de Arouce 2010 ($20), from 80 percent baga and 20 percent touriga nacional in Beiras, takes advantage of a fruitful collaboration with used French oak barrels to produce a big yet elegant, licorice-scented beauty. Any of your fancy guests who pull you aside to ask discreetly how much you paid for that bottle, tell ’em $75.

In Bairrada, the baga grape reaches its apogee. A simple but distinctive version is in the Bairrada pioneer/provocateur Luis Pato’s Colheita Seleccionada 2011 ($13), which is brambly, inky, mammalian, rustic, though at only 12.5 percent alcohol bears its muscle with admirable grace. Campolargo’s Rol de Coisas Antigas 2009 ($30), at a whopping 15.5 percent alcohol, pulls to the other end of the spectrum. That high alcohol is barely noticeable, given how well integrated it is. Like a silkier, more balanced Napa cabernet sauvignon from an era too far in the past, it’s old, elegant and earthy. Licorice, white pepper and spearmint predominate, but above all it’s the integration, the cohesiveness of the wine, that remains memorable.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story