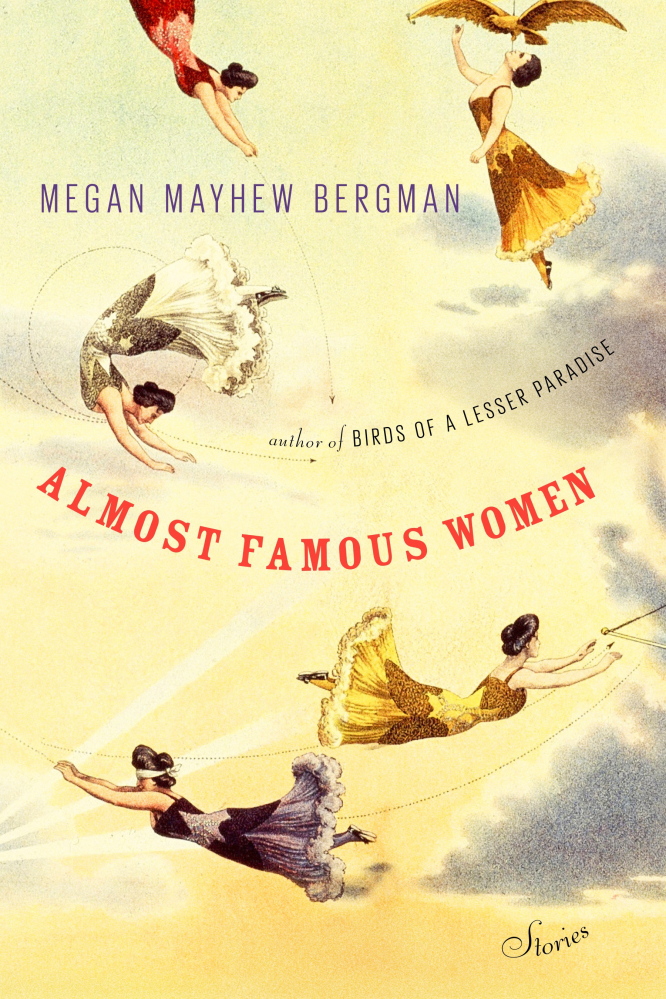

The dust jacket on Megan Mayhew Bergman’s second story collection depicts several women floating in midair, as they crisscross on a flying trapeze. It’s a fitting metaphor for the stories within. “Almost Famous Women” is a high-wire act that combines large ambitions with larger-than-life characters. The result is intriguing, wondrous and complex.

Mayhew Bergman is a fan of historical fiction and quick to point out that her book is not that. Rather it is pure fiction, grounded in history with ample supporting research.

The author studied the lives of some dozen notable yet unsung women who lived on the edge, most during the 20th century, and she spun tales about their lives.

Her subjects include a speedboat racer, actress, daredevil and dancer. Some are familiar by way of their well-known lineages – among them, James Joyce’s daughter, Lucia; Lord Byron’s illegitimate child, Allegra; and Oscar Wilde’s niece, Dorothy. Others are more obscure. What ties them together is the book’s genius.

“I’m fascinated by risk taking and the way people orbit fame,” the author says in her notes. “I wanted to explore the price paid for living dangerously.”

So she plunges us into the thick of lives that center loosely or residually around fame, sometimes in a spiral of illness, madness or substance abuse.

In “Norma Millay’s Film Noir Period,” we encounter the sisters of Maine poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay, and the rivalries that ensue when talent and recognition are shared unequally. ” ‘Tell me,’ (Edna) said pausing in the doorway, owning every inch of her five-foot frame. ‘What kind of ride is it, on my coattails? Is it good?’ ” writes Mayhew Bergman.

In “Romaine Remains,” a renowned painter and fading diva, now 93, places her trust in a houseboy who has his own aspirations: “I do not care for her, Mario thinks. I do not feel sorry for her. I only want to take some small slice of her life and have it for myself.”

In “Hazel Eaton and the Wall of Death,” a runaway teen escapes the quiet of coastal Maine’s loons and lighthouses for the thrill of motorcycle stunt driving. Although she has second thoughts about the daughter she had to give up, she now lives for the freedom and applause of the carnival life. Mayhew Bergman writes, “She was questioning then, as she does now: what makes you empty and what makes you full?”

As these examples suggest, the stories are far-ranging, broaching issues of envy, longing and betrayal. In one sense, this book is a series of object lessons on love and the obstacle course that some people set for those who dare to come close.

We witness the inevitable heartbreak of dreamers, lovers and hangers-on, for whom reflected glory may, or may not, be ample reward. As one character says, “I lived vicariously through Dolly. It had always been that way; it was our currency.”

If a couple of the entries in this collection fall short, it’s because of the company they keep. The stories here are largely stand-outs that would easily hold their own without the larger thematic framework. Mayhew Bergman slyly adds unexpected links among several characters from different stories, particularly those who served and suffered in World War I. As a result, some of the tales take on a synergy, as if in conversation with one another.

“Almost Famous Women” is lyrical, haunting and smart. It may be that fiction benefits from a foundation in history, gathering added weight. Nonetheless, these stories pack a wallop. Their focus on near-fame mingled with danger provides a fresh and singular edge.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story