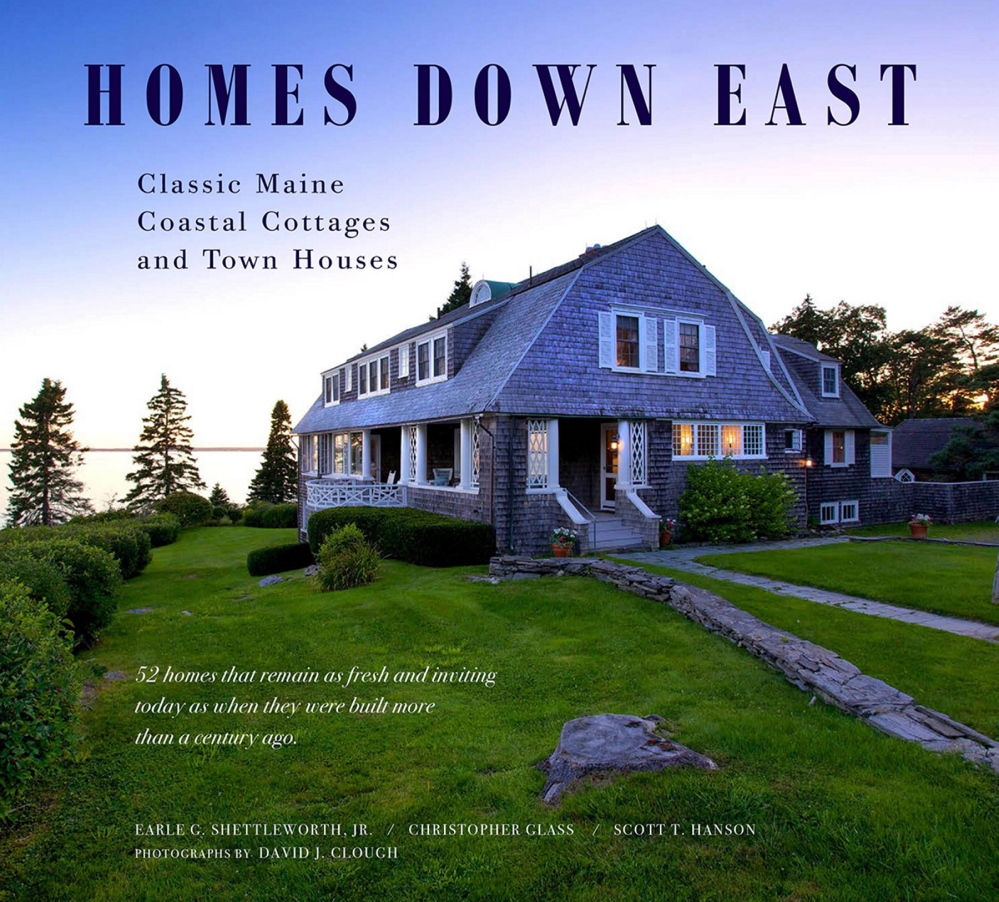

For those who appreciate architecture, especially Shingle Style cottages and homes, “Homes Down East: Classic Maine Cottages and Town Houses” is a must read and a must view.

Two of the region’s most informed architectural historians have teamed up with noted architect and longtime Bowdoin College instructor Christopher Glass to write the text. They are Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission and state historian, and Scott T. Hanson, historian with Sutherland Conservation & Consulting in Augusta. The book is visually bolstered by contemporary color photographer from Rockland’s David J. Clough.

Focused on 52 mostly Shingle Style residences built 100 years ago or more, the book offers the clearest anatomy of the style since 1955. The entries on each study are graced by Glass’ critical commentary.

Each of the structures featured appeared in the Scientific American – Architects’ and Builders’ Edition or successor magazines, including American Home and Gardens, between 1892 and 1911. These entries are brought together for the first time and create a ready tool for researchers who may have utilized them previously in scattered form.

Bundling the Maine houses from Scientific American would have made a solid book in itself, but here we are given an enjoyable and detailed examination of each building and fresh new images to match historic images and floor plans.

As savvy readers may expect, the authors focus a lot of attention on the Portland-based John Calvin Stevens (1855-1940), who was involved with more than 20 of these projects. His commanding work also was influenced locally by the Fassetts and the Boston architects W. R. Emerson, H.H. Richardson and R.S. Peabody.

A good deal of space is given to architects such as Chapman & Frazier, designer of what is now former President George H.W. Bush’s summer home in Kennebunkport, as well as Frederick L. Savage, Henry Paston Clark and many more. I was particularly charmed to find six designs by Portland High School teacher Antoine Dorticos (1848-1906), who had Fassett training, reached out to a national audience and promoted Casco Bay as a vacation spot.

The first of the 52 Maine houses is a simple Queen Anne style dwelling, the John W. Thompson house in Gardiner (1891). Though still standing, one might hardly recognize the abode as a forerunner of the Shingle Style. Built for mill workers, it stands as “perhaps the foreshadowing (of) future geometric adventures.”

“It is against the backdrop of houses such as these that other architects published by Scientific American Builders Monthly created the new cottages of the Shingle Style,” Glass writes.

That building type, known as the “odd cottage” in its day, would come to be seen as particularly refreshing and original.

As the authors note, these cottages “have become so identified with Maine that they can be considered an iconic part of Maine’s image in the 21st century.”

The era of the Shingle Style, “with open floor plans, asymmetrical window placements, dramatic roof lines, and a new way of relating to the rugged coastal terrain,” lasted roughly from 1880 to World War I. The style was given identity by the great Yale scholar Vincent Scully in his book, “The Shingle Style” (1955).

Not only did he fix the name, but in the minds of many it became the most inventive and representative style in Maine, a vision returned to since the 1970s.

William David Barry is the author of “Maine: The Wilder Half of New England” and co-author of several books. He lives in Portland along with his wife and cat.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story