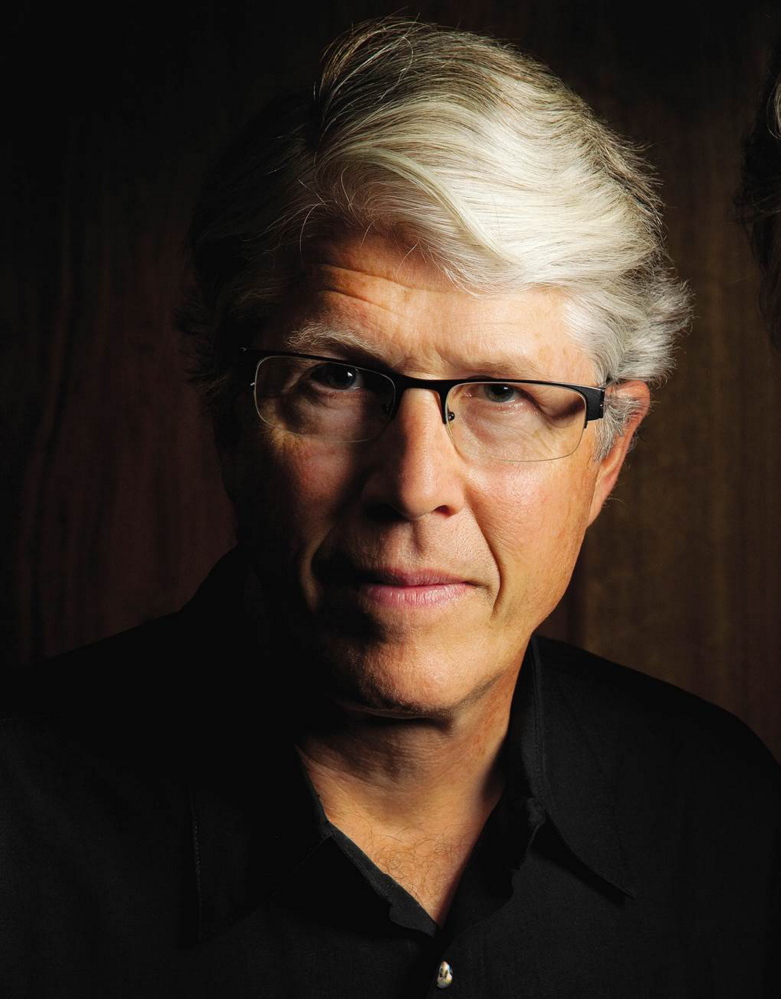

If the name Douglas Preston rings a bell, there are good reasons. Preston is half of the duo, with Lincoln Child, who have written the Agent Pendergast novels including the current bestseller, “Blue Labyrinth.” He’s also a journalist-explorer who has documented his expeditions to the desert Southwest and elsewhere in such books as “Cities of Gold.” And he’s a crime reporter whose acclaimed book about a serial killer in Italy, “The Monster of Florence,” is being adapted for the big screen with the prospect of George Clooney playing the role of Douglas Preston.

Last summer Preston formed Authors United, a group of some 900 writers, that made news in a widely publicized contract dispute between online retail giant Amazon and publisher Hachette Book Group. At issue were Amazon’s negotiating tactics, which targeted Hachette authors by impeding sales and distribution of their books.

If it seems that Preston gets around, he does indeed. This polymath who began his career as a writer and editor at the American Museum of Natural History has packed several lifetimes into one. Unlike people who dabble in many arenas, Preston immerses himself in his pursuits. For one of his books, he retraced the route of Coronado, traveling 1,000 miles across Arizona and New Mexico on horseback. “As I read the old Spanish reports,” he says, “I realized that I wasn’t getting the grit between my teeth, I wasn’t feeling the heat of the sun. That’s why I had to get involved.”

The author, who divides his time between New Mexico and Maine, spoke recently about Amazon, celebrity and the art of the thriller. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: As an Amazon customer, you know how consumer-friendly the company is. Were you surprised by their treatment of authors?

A: I went into this thing thinking that Amazon was making a mistake by targeting authors, and they would realize this was not the right thing to do. They would especially realize that inconveniencing their own customers is not the way to get what you want.

Q: By punishing authors, they’re also punishing readers – and there are millions of us. But the dispute has been resolved?

A: Yes, Hachette got a great deal of what it wanted. Amazon takes 30 percent, Hachette takes 70, and Hachette retains, to a large extent, the right to price its own books.

But this resolution does not solve the main problem, which is that one company controls over 50 percent of the U.S. book market. Amazon is a monopoly as much as Standard Oil was when it was broken up. But never in our history has one company controlled a media market the way Amazon controls books. And that’s really scary.

Authors receive advances from publishers – it’s a kind of venture capital for ideas. But with publishers being squeezed so hard by Amazon, they’re making less money and paying lower advances. Even worse is that risky books – books that have unusual or unpopular ideas – don’t get published when they would have been published before. That is a great harm to our democracy, a huge loss. We’re going to the Justice Department to ask them to please look into this situation. You know, it’s a big undertaking to go after Amazon. It’s like going after Microsoft or AT&T.

Q: Let’s talk about your books and the unusual path you’ve taken.

A: I started off as a nonfiction writer and journalist, writing mostly about science. I still write about science, archaeology, anthropology and paleontology for The New Yorker, The Smithsonian and National Geographic. But I just don’t want to be bored. I love writing books with Lincoln; he’s really fun to work with.

Q: Are there readers who knew you primarily as a science writer, who consider your thrillers to be a kind of slumming?

A: Well, I do want to dispel the view that I’ve somehow sold out, or I’m writing for money. What I like about the basic concept of a thriller is placing people in extreme circumstances – and let’s see what happens. And, it turns out that I love writing these thrillers. I get a big kick out of putting them together.

Q: Where does this elitism come from, that idea that one genre is more worthy than another, when you can read a well-written thriller or a lousy book of science?

A: It’s quite true. Let’s take a book that has extreme graphic scenes of war and violence, sex and killing, deception – and you have “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.” If these had been written today, they would actually fall under the term “thriller.”

You know, thrillers don’t try to be anything that they’re not. They’re honest books, and that’s one of the things I like about them. Thriller-writers also tend to be honest, straightforward people who love what they do and are well aware of what they’re doing. They’re not involved in self-deception, unlike many literary authors I know.

Q: Are you able to gain insight into real people through the character of Agent Pendergast?

A: Pendergast is more real to me than many real people I know. He’s chilly, awkward in expressing emotion, he’s excessively formal, snobbish and pretentious. He has very old-fashioned values, but he’s a difficult person to be around. Even though he’s never going to walk through my door and shake my hand, he’s vividly real to me.

I think, in general, if you want to be a good novelist, you have to have a lot of empathy. You really have to be able to put yourself in another person’s shoes, and feel the world and see the world the way he would – not the way you would.

Q: What are the limitations of writing a series around a single strong character?

A: The most dangerous thing is if the writer gets bored with the character and starts churning out books with a formula. I’ve seen that happen. Lincoln and I have a mortal fear of falling into a rut or of going downhill.

Q: Does that shared fear help to prevent the series from becoming formulaic?

A: We kill each other’s little darlings, so to speak. In other words, when Lincoln says to me, “Doug, this is no good, this stinks,” I might get angry, but he’s right. That’s why we have a partnership. I trust his judgment, he trusts my judgment. We’re constantly challenging each other, and crossing out stuff that the other has written. It’s a difficult process and sometimes I feel like we’re an old married couple sniping at each other.

We had to learn how to fight, the way married couples have to teach themselves how to fight. We’ve got a very constructive way of fighting now. If we really find ourselves going at it for five minutes, we realize there’s something wrong with both of our approaches – let’s find a third way. It happens all the time.

Q: At this stage, do you prefer writing alone or together?

A: Honestly, I prefer writing with Lincoln. People seem to think it’s difficult working with a writing partner, but it’s a lot easier than trying to write on your own. Writing is a very lonely business, sitting in an office by yourself, staring at a computer like a glorified bank clerk. You have no one to bounce ideas off. I have found myself writing chapter after chapter, then realizing I’ve been going in the wrong direction, sometimes for weeks. I have to throw everything away and start over again. Whereas Lincoln usually says, “Whoa, whoa, where are you going here?”

Q: Are you working on a book together now?

A: Yes, the next book in the Pendergast series. We don’t have a title yet.

When we’re working together, we’re re-writing each other’s material, so we’re in a very intense kind of partnership. We’re in contact almost every day by email or phone. Whereas when Lincoln is working on a solo book, and I’m working on a New Yorker article, we can go a week or two without being in contact. Lincoln will send me his manuscript, and I’ll read and critique it. We both do that for each other.

Q: You keep going back and forth between fiction and nonfiction. At this stage, which do you prefer?

A: You know, when I’m writing fiction, I’m thinking, “Gosh, wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a skeleton, a framework of facts to be working from?” Then when I’m writing nonfiction, I’m thinking, “God, I feel totally enslaved by this framework of facts that I have to work with.”

I think writing nonfiction really enriches my fiction, and writing fiction – that is, figuring out how to tell a good story – really helps me in writing nonfiction. With some people, the beautiful metaphors flow effortlessly from their pens. I really have to struggle to achieve a good prose style. I have a great respect and love for the English language, so I’m never satisfied with what I’ve written.

Q: Are there ways that living in Maine helps your work?

A: When I moved to Maine in 2004, I realized that it’s a wonderful place to work because the weather cooperates. I love Maine weather, the quietness of Maine, the fact that people in Maine are not impressed. They don’t give a damn, and that’s really good for a writer. I think writers who cultivate celebrityhood ruin their careers and their books. Truman Capote is a perfect example of that, a very great writer who just ruined himself by becoming a celebrity.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story