George Pelecanos is among our most prolific – and compelling – crime novelists, a writer who evokes his hometown of Washington, D.C., much as Dennis Lehane does with Boston or Michael Connelly Los Angeles: as a character in its own right. Complicated, riven by conflicts of race and class and identity, his Washington is not the city of the politicians but a more hardscrabble place in which the only law is that of survival and opportunity is often just another come-on, another lie.

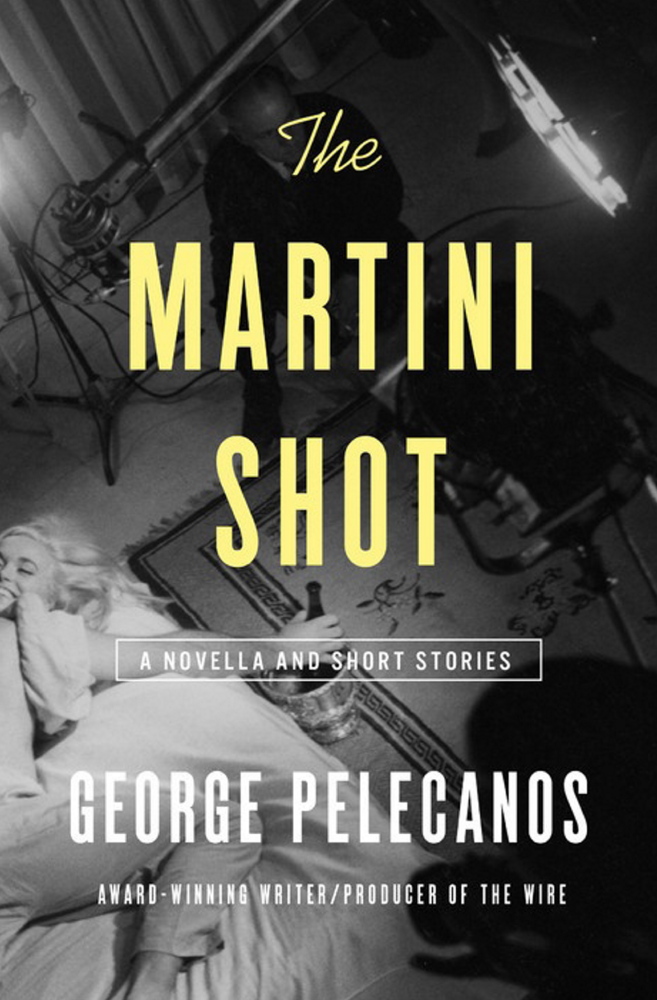

Such a Washington sits very much at the center of “The Martini Shot,” Pelecanos’ first volume of short fiction after 19 novels, which offers a primer of the author’s themes and fascinations, albeit in attenuated form.

There is basketball, which operates as both escape and social lubricant, a way to forget the streets for a while. “I got problems at home, I got problems at school, I got problems walkin down the street,” notes Tonio Harris, the teenage protagonist of “String Music.” “I prob’ly got problems with my future, you want the plain truth. When I’m runnin ball, though, I don’t think on those problems at all. It’s like all the chains are off, you understand what I’m sayin?”

There are callbacks to the novels – a cameo by Pelecanos’ old detective/fixer Nick Stefanos in “The Dead Their Eyes Implore Us”; the origin story of Spero Lucas (the main character of Pelecanos’ two most recent books, “The Cut” and “The Double”) in “Chosen.”

And always, there is the push and pull of the have-nots and never-weres. “The businesses along here,” laments Verdon Coates in “The Confidential Informant,” “were like a roll call of my personal failures. The Murray’s meat and produce, the car wash, the Checks Cashed joint, they had given me a chance. In all these places, I had lasted just a short while.”

There is, however, a grab-bag quality to “The Martini Shot”; of the eight stories here, six have been published previously in different anthologies, including “D.C. Noir,” which the author edited in 2006. This is both the charm and, ultimately, the weakness of the book, which reads in many ways like a hastily stitched together quilt.

“The Confidential Informant” is the first and perhaps finest piece in the collection, the story of a marginal police informant who finds redemption where he least expects it, although at quite a cost. Most moving is his nonrelationship with his father, a Vietnam veteran who sees his son for who he is. “My father didn’t even turn his head,” Verdon tells us. “I would have watched some of that old Steelers game with him if he had asked me to, but he didn’t, so I went upstairs to my room.”

Here we see what makes Pelecanos’ best writing so resonant: the sense of longing, of miscommunication, the way love does not enlarge us but rather makes us small. A similar movement marks “The Dead Their Eyes Implore Us,” about a Greek immigrant in the 1930s coming to terms with the treacherous social landscape of the New World, or the tragic and understated “Miss Mary’s Room,” which traces a youthful friendship and the betrayal that transforms it at the core.

“The truth is,” the narrator of “Miss Mary’s Room” insists, “I got no deep remorse for what got did to Pat. Pat was in the game and he knew what time it was.” The inference is that in the territory these characters occupy, regret is a luxury no one can afford. Even so, the narrator can’t help but feel for his friend’s mother, whom he imagines “sitting on the edge of her bed. Praying the rosary.” It’s a vivid image, unsettling and open-ended, not unlike the story itself.

The trouble with “The Martini Shot” is that too often its stories are vestigial, not fully fleshed out. This can be a problem when a novelist turns to short fiction, which requires a certain brevity. For all its necessary back story on Spero, “Chosen” reads more like a compressed bit of family history than a driven piece of narrative. “When You’re Hungry” comes off as something of a gimmick, a bounty hunter saga gone astray.

Pelecanos is at his most effective when he writes in the first person, embodying his characters with a sense of personality and voice. Yet even in these efforts, he tends to fall back on a sort of shorthand, dispensing with descriptions quickly, as if they were stage directions and nothing else.

“A guy sat facing a good-looking blonde in a booth against the far wall,” he writes at the start of “Plastic Paddy,” which meanders through a night of youthful indiscretion, without much consequence or point. Reading such a story, we are left with a sense of a writer operating at less than full speed, held back by the constraints of a form in which he isn’t entirely at ease.

That’s especially true of the title novella, narrated by a writer and producer on a network crime show. Pelecanos knows this material; he has worked on both “The Wire” and “Tree,” and his evocation of productions as “circuses that arrived in town and brought excitement to the locals for a short period of time” is trenchant, on the mark.

Why then does this effort fall so flat? Partly, it’s the setup, in which the narrator turns detective after a friend and crew member (with a sideline in high-end cannabis) is shot and killed. But even more, it has to do with the headlong quality of the writing, which feels rushed, out of breath. Characters are sketchily drawn, as if they were TV players, and a number of scenes are written in teleplay format as if to highlight the blurry line between reality and imagination. Pelecanos makes the point explicit when he writes, “It’s like I imagined half the (stuff) that went down.”

The intent is clearly meta, a commentary on the limits of form. Even so, it seems tacked-on, contrived, lazy almost – a superficial way to engage a complex idea. The same might be said of this collection, which is at best a stopgap between more essential books.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story