Pundits talk about race sometimes. People of color talk about it every day, as part of the fabric of their daily existence.

But white people talk about it only occasionally, as a general rule, and mostly among other whites, except for those times when the tragedies of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin or Rodney King force discussion across racial lines into mass culture.

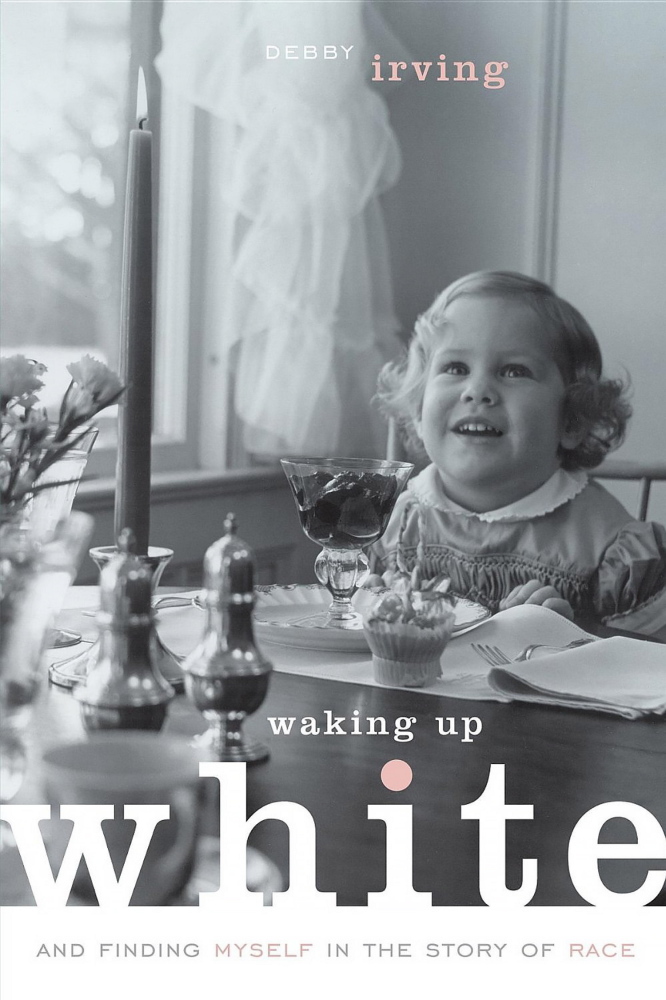

Race, Debby Irving asserts in her new book, “Waking Up White: And Finding Myself in the Story of Race,” is what she calls “the elephant in the room.”

Irving’s book is an immensely brave and important cultural memoir. It is, as she writes, “my story of racial ignorance.” It tells of her life-long journey from childhood ignorance and confusion, to a patronizing desire to “help fix” things, to a deep, personal exploration of her role and the dominant (read: white) culture’s role in sustaining and perpetuating systematic racism. Her journey has brought her to earnest, insightful engagement – and to the writing of her book.

Irving, who spends summers in Maine, peels back the veneer that keeps people from seeing the issue of race for the interconnected, soul-crippling dynamic that it is. The book is a story of her journey, but it is also the story of race in America. She ends each chapter with a question for readers to ponder, a personal assessment of some racial factor that shaped her life and, no doubt, shaped that of readers’ as well.

Following is a conversation we had about her book and about the issue of race in America, lightly edited for length and clarity.

Q: You describe our reluctance in America to talk about race as being an “epidemic of silence.” Can you explain what you mean by this?

A: Whites I meet will commonly say, “I’m so afraid of offending people.” But when I dig deeper, it’s much more about revealing their ignorance on race. Talking about it is messy. When you live in a culture that is risk averse, we don’t learn how to talk about conflict. For a very long time, I didn’t have the confidence that a blowup in such a conversation could be resolved.

In the book, I write about our prevailing culture of “niceness.” The epidemic of silence is tied to the culture of niceness.

Q: I found it fascinating that you were in your thirties, while working toward your master’s degree and enrolled in a course entitled “Racial and Cultural Identity,” before you shockingly discovered that you belonged to a race.

A: About five years before I took that class, I was talking with a friend of mine, a woman who came to American from Trinidad, a black woman. She was telling me about a group in her church she was involved in, and that it was amazing to her that white people didn’t think they have a race. That actually included me. It was a moment when I chose to be silent, yet it would have been a perfect moment to speak up, to wake up.

When we – whites – talk about race, we’re talking about brown and black people, people of color. Not about whites and the historical roots of racism, and our part in perpetuating it. In a newspaper story about a 54-year-old woman, for example, if she’s white, she’ll be described simply as a 54-year-old woman. But if she is black, you’ll read about a 54-year-old black woman. In the first instance, in our white-dominant culture, it’s implicit that she’s white. But if she’s a person of color, that always gets included. Occasionally, it’s important information, but usually not.

When white people admit to me that they themselves do this, and that they promise they’ll work on it, I tell them, “Don’t stop. Instead, when you talk about a white person, include that they’re white. People will ask you why you did that. And then you can explain the whole the thing to them.”

Q: You write about the “hidden” reality of systemic racism that enables many white people to believe that they’ve succeeded by their own hard work and merit. And, that they look on people of color who fail as lacking in those qualities. Comment on that.

A: Race is the elephant in the room. Not everyone in this culture knows or understands about systemic racism. They think people of color are inferior. And every person of color knows that whites have it better, though they may not understand why.

I used to be very critical of welfare. That people should only be on it for a short time, that they should “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” But I now see that my family of good New England stock has long been on government assistance.

The GI bill made it possible for my father and uncles to go to college and to buy their first homes with low-interest FHA loans. The government gave out millions under the GI bill, but only 4 percent went to returning black soldiers. From 1934 to 1963, the federal government underwrote $120 billion in new housing loans, but less than 2 percent went to people of color. Social security as well was created in a way that favors whites and excluded laboring people of color.

My family benefitted hugely from “big government.” It’s a myth that my family achieved success solely on hard work and merit. These programs reinvent racism, and they perpetuate it.

Q: You wrote about your journey, of being inculcated with the idea that people of color were inferior, and that you were motivated to want to “help fix” them. And you were surprised when they weren’t grateful.

A: I spoke at the NAACP last night, and one person mentioned a book by Jason Riley, “Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to Succeed.”

I grew up believing I owed it to the world to try to help, that maybe I could help people of color be more successful. I had no idea when I got involved that it was resented. Working in inner-city programs, trying to be all cheery and chirpy and helpful – it was so patronizing. But we don’t have any idea what all is at play. The resentment was palpable. And I would think it showed that they had a complete lack of gratitude.

I wasn’t doing anything to dismantle racism. All I’d done was do something in order to feel good about myself.

Q: The race issue in the United States seems to be compounded by the idea that it’s nearly impossible to gain understanding about soemthing when you don’t recognize your own ignorance.

A: (American historian) Daniel Boorstin says that “education is learning what you don’t know you don’t know.” This goes back to the lens through which we see the world.

In this country, the dominant white, Euro-American culture has never been challenged. It has marginalized people of color. If you don’t know the history, you look at marginalized people and see them as inferior.

It’s very human. It’s not about being evil. You see things only the way you know things, which doesn’t enable you to challenge your beliefs.

Q: You make clear that in a person’s early journey to get beyond racism, talking about it can be a minefield – where you don’t know what to say, and are afraid to say something stupid or hurtful.

A: In a marriage, or any relationship, there is this idea of a “third space.” That one person brings one set of behaviors and beliefs, and the other brings another. And there’s conflict because the other doesn’t behave the same way you do. What is needed is a third space.

We can’t make it work unless we’re aware of ourselves. We need to create a ‘third space’ that works for all of us.

Our society is a third space, but up until now it has been a white space. It is important that whites shift from seeing people of color as deficient to seeing all the strengths and talents and skills that they bring. They possess a particular form of resiliency and resourcefulness, which is common in populations that are marginalized. There is a lot of talent and wisdom that they can bring to that third space.

Q: So how do we start to move beyond racism?

A: Talk about it.

But it is very important for white people to do their education on their own. People of color are exhausted from having tried to educate us for 400 years. Look for other white people who are further along, and talk to them. And then start engaging in cross-racial ways.

I don’t like to use the word “racist.” It’s too static. I talk about being “racialized.” It’s like being socialized. It’s a process. Moving beyond racism is all about the process.

Frank O Smith is a Maine writer whose novel, “Dream Singer,” was released in October 2014. It was a finalist for the Bellwether Prize, created by best-selling novelist Barbara Kingsolver “in support of a literature of social change.” Smith can be reached via frankosmithstories.com.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story