Chef David Levi is picking pine needles out of a freshly harvested five-pound maitake mushroom, also known as a hen of the woods, and trying to dredge up the name of a movie. Not a movie he’s seen; he can’t recall seeing a single movie since opening Vinland last December. What he’s trying to conjure is the name of a movie he might have merely heard of, a title that might have wormed its way down into his very crowded consciousness over a long winter, a worrisome spring, a booming summer and now the bounty of fall.

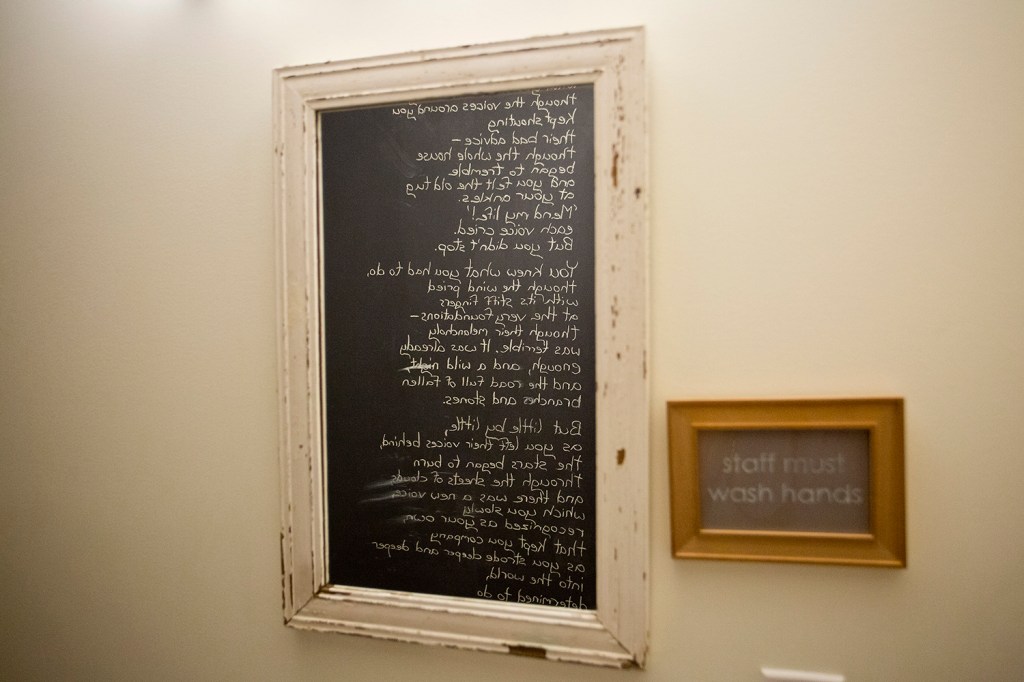

He gives up. On a micro level, the mushroom needs his focus. On a macro level, Vinland always demands his attention. Once upon a time he could explore Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, looking for mushrooms himself. Now he has no time to forage. His best friend called days ago. Levi has yet to have a chance to call him back. He hasn’t read a novel in way too long. His girlfriend barely gets to see him – “and she lives with me.” Outside, Maine is in the throes of October’s fiery glory. It’s what Wendell Berry described as the “sharp sweet of summer’s end” in “The Wild Geese,” the poem currently featured on the rotating chalkboard poetry walls in Vinland’s bathrooms, when we’re all in “time’s maze over fall fields.” The harvest season is here, a happy thing for a 100 percent local food restaurant, but not without its pressures. It’s time to put up that bounty, like this maitake, which will be sautéed in clarified butter and frozen for use in the winter.

But despite the pressure and the lack of free time, Levi is feeling good overall. There might still be some Vinland skeptics around Portland, but Levi has a staff he likes, including a new chef, Daryle Degen (his former sous chef, Ryan Quigley, left about a month ago for Boston’s Puritan & Company) and a general manager who is a “rock.” Moreover, his team recently returned reinvigorated from an overnight trip into the woods of New Hampshire for their first team-building exercise (complete with cooking together over coals, cheating on Vinland’s usual 100 percent local edict with lemon, and some foraging for good measure). And cash flow, while still an issue, had been vastly improved by summer’s flood of tourists and new customers from Maine.

JULY 4, CONGRESS SQUARE PARK

It started slowly. Other restaurateurs had told him not to expect business to pick up until after the Fourth of July, but still, June dragged on. He shook up the menu with a new small plate theme – letting customers build a meal of any five plates for $60. He’d had good press in the Wall Street Journal in May. The cruise ships came in, but those passengers never seemed to make it up the hill. He decided to stay open on the 4th itself; other restaurants were closing, but if there were customers to be had, he resolved to take advantage. “It turned out to be a really big night for us,” he said. For the next couple of weeks, there would be sporadic bursts of business, huge nights on a Monday or Tuesday and then relative calm again. Then around the middle of the month, high season started in a big way. “Every night was a huge night until Labor Day,” Levi said.

A big night at Vinland equates to about 70 covers, restaurant-speak for diners. “I knew the absolute maximum would be like 80, and there were a few nights that were like that,” Levi said. In the height of summer, customers divided pretty evenly between locals and seasonal visitors, including a high proportion of Québécois. “For whatever reason they were among our most enthusiastic patrons,” he said.

GOOD NEWS

Over the course of a few short weeks, he got a five-star review from this paper, Wine Enthusiast magazine mentioned his turnip soup and Food & Wine magazine featured his crab salad. Coming off that high, he admits it was disappointing to be ignored in a recent Boston Globe feature story that fawned over Portland food.

“It’s super important to continue to get press,” he said. He remembers getting a lesson in that from friends of his parents who were in the restaurant business in Manhattan for decades. “They said that when they were on the cover of New York magazine they thought, ‘Oh, now we made it.’ And it turned out like, ‘No. Now we made it for the next two weeks.’ That kind of thing can be fleeting.”

He also fears that the perception of success might scare away potential customers who don’t want to compete for a table. “A former server stopped in last night to have a drink,” Levi said. “And said ‘Wow, whenever I walk by, you guys looked packed.'” That’s great, Levi said, and he hears it regularly from friends and suppliers except, “I also know that we have room for a fair number more people. It’s not high season anymore.”

COOL YOUR PACOJETS

The end of high season has brought a moment’s respite to evaluate what worked and didn’t. Vinland tried selling ice cream out the back door, but without the right equipment, he couldn’t make any money. Levi would do it again, if he could afford a Pacojet, the Swiss-made, super-efficient appliance beloved of chefs. “The Pacojet just makes for an exceptionally creamy mouth feel,” he said. “But we can’t afford it.” He doesn’t expect to have the kind of money ($5,000) it would cost anytime soon. He’d also love a flash freezer, but that’s even more high-end (30K, he estimates, if he shopped well). “I’ve thrown the idea out to a couple of friends in the industry here in town about sharing one,” he said. If Urban Farm Fermentory could be the repository and 30 or so businesses wanted to share the flash freezer, that would be doable. “Who knows?” Levi said. “I think that kind of thing is always fun.”

But he’s acutely aware that not every restaurant owner or chef in town appreciates that kind of a sharing business model. “I think there are divergent trends within the Portland food community,” Levi said. “Some people want it to be very, very cooperative and inclusive and some people want it to be cutthroat. I tend to very much be on the cooperative, inclusive, friendly end. I tend to be targeted by people on the other end.”

THE JOURNEY

Right now Wendell Berry’s poetry graces one bathroom (Levi has a master’s degree in poetry); the other one features a Mary Oliver poem called “The Journey.” It begins with these lines:

One day you finally knew

What you had to do, and began,

Though the voices around you

Kept shouting.

As the poem goes on, it seems clear it is about the struggle to meet the demands of both parenthood and the creative impulse.

But if you view it through Levi’s eyes, maybe it also represents what it means to face negativity in a hot food town. It’s not always stated bluntly, but the sniping has been pronounced enough that the chef at Portland’s Petite Jacqueline, Fred Eliot, felt compelled to defend Vinland (and Levi) in a September interview with Eater Maine. “He got so much crap for wanting to open an all-local restaurant,” Eliot told the publication’s interviewer. Levi knows all this. He’s too new to this business to realize you never read the comments, so he knows whenever someone bashes Vinland on Eater Maine. (He instituted a comment card system at Vinland in the summer, encouraging customers to write down exactly what they thought of his place. Vinland tweets out the nice ones from time to time.)

The skepticism has extended to customers as well. “A surprising number of people come in and at the end of the meal say they had come in as skeptics,” Levi said. “I had never really thought about that before – being a skeptic of a restaurant.” He sounds genuinely puzzled. Why wouldn’t someone trust that a 100 percent local meal could be delicious and not bathed in unpleasant-tasting sanctimony?

“Our ambition is to build a sustainable local food economy and with that to build more of a sense of identity as a pillar of a distinct regional cultural identity,” he said. “I don’t know what there is to object to about that – unless there is someone who thinks we aren’t doing it well.”

Some customers told him that he wasn’t making the 100 percent local (except for the drinks) aspect of the Vinland mission obvious enough. So he added a line to the menu recently “100% local food, down to the salt.” But in fine print, he added. “I don’t want to be bludgeoning people with it. I really don’t.”

SQUIRRELING AWAY

While Levi is prepping for the daily service, Jules Fecteau from Serendipity Acres in North Yarmouth (all organic, all pasture-raised, which suits Levi’s ideas about how chickens ought to live) comes by with the weekly chicken order. They talk about what he’s doing with her birds, namely preparing them with sage and some alchemy involving crisping the skin, and she tells him she’s madly processing chickens. “I’ve got 160 to do,” Fecteau says. “All of them for the winter. I close my eyes and I see chickens.”

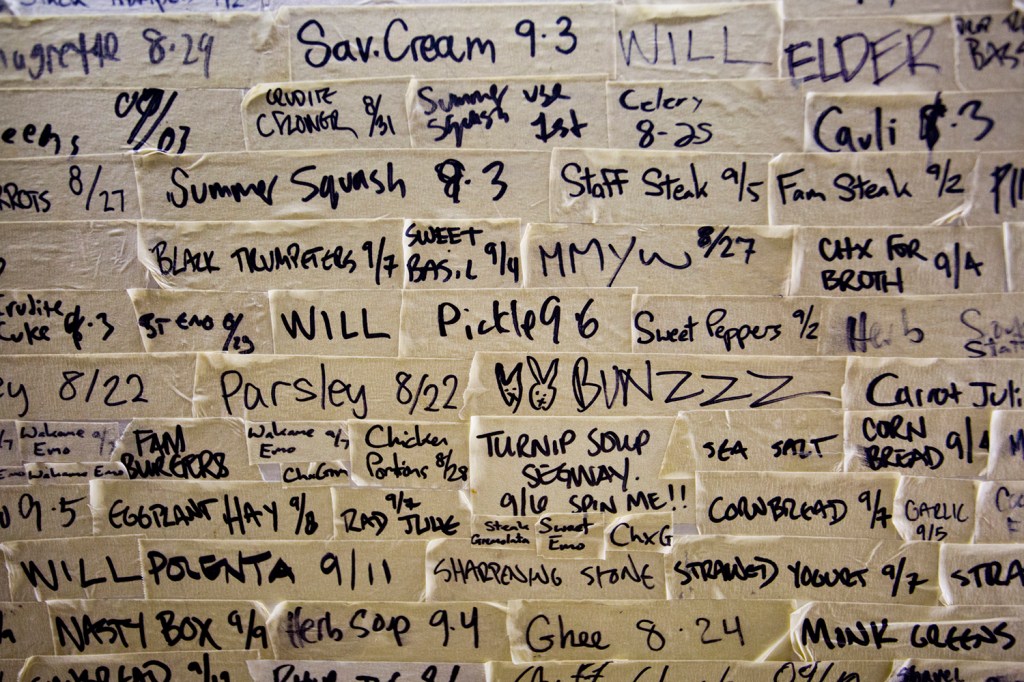

Levi is preparing in his own way, and heading into a Maine winter, he says he’s definitely in better shape than last year at this time. “No comparison,” he says. For one thing, he’s got a place to store his root vegetables. In June, he and his staff built a walk-in. They’ve been dehydrating tomatoes, putting up applesauce and watching for just the right amount of frost to hit before foraging for items like rowanberries, which bartender Alex Winthrop blends into a simple syrup with Campari-like flavors.

Winter also means bringing in customers in different ways. On Oct. 29, Vinland will host an event attended by a vintner from Italy’s Dolomite region who Levi admires, Elisabetta Foradori, and featuring all Maine foods in a Northern Italian-style dinner. In early December (date not yet determined), the restaurant will have another dinner with Sicily-based winemaker Frank Cornelissen. Levi is also hoping to host some farmer dinners; he’s already cooked at one of the Flanagan’s Table events – an elegant dinner series held in a barn in Buxton.

He gets nice invitations to visit farms but won’t be saying yes anytime soon. Free time is an issue. “I have none essentially,” Levi said. “Which someday will have to change.” This pace is not sustainable. If you were his mother (who has eaten at Vinland with his father about a half-dozen times), you would probably fret that he looks thin(ner). And yes, he’s aware of the irony that running the Maine restaurant most intensely committed to celebrating and utilizing a sustainable food economy is not something that he can personally sustain for the long run.

But for now, he says, he’s lucky because he is getting to carry out his dream. “It’s certainly not going to make me rich, but that’s OK,” he said. “Maybe someday I’ll have another restaurant that can do more volume.”

This summer, on one of just two nights he took off, he came in to eat with his girlfriend on a Thursday night. “We sat at the bar and just watched everything coming out right, and the place was full of happy people.” Winthrop blew his cover with another couple sitting at the bar, outing him as the chef/owner. The couple bought Levi and his girlfriend a bottle of wine. “It was so nice to be able to just sit back a little and have some wine while restraining myself as much as possible from going into the kitchen to micromanage,” Levi said. “It seemed a positive harbinger of days to come.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story