TEMPLE — When Wesley McNair’s mother became sick several years ago, he reached out to her family in the Ozarks. Ruth Willard had long ago made her home in New Hampshire and become a “damn Yankee” in her relatives’ eyes. But, by hearing their stories and later carrying his mother’s ashes home to southern Missouri after her death in 2012 at age 91, Maine’s poet laureate said he unearthed “my Ozarkian self.”

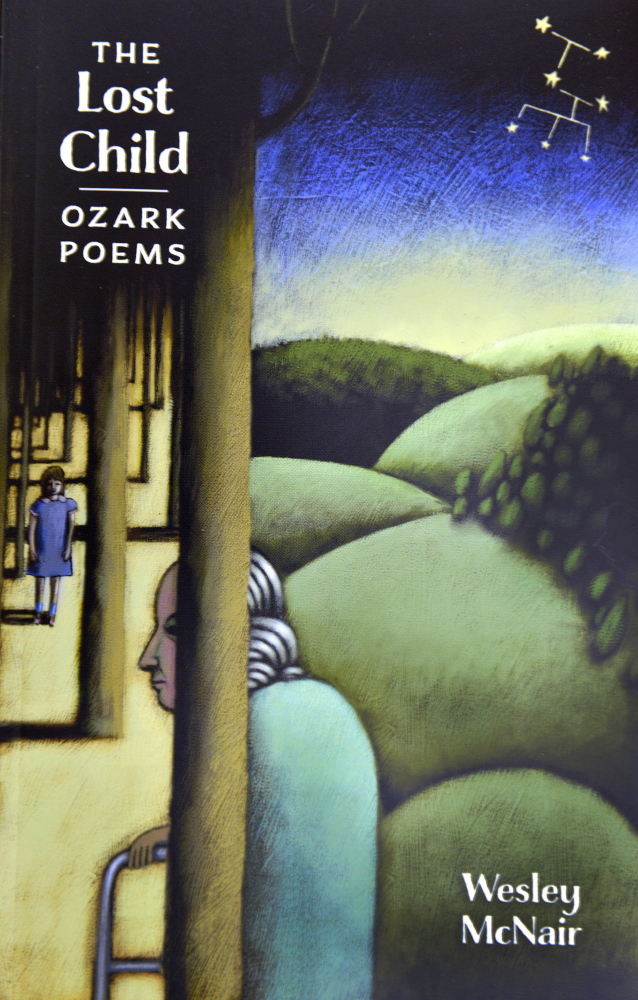

McNair’s latest book is “The Lost Child: Ozark Poems,” a volume of long-form poetry inspired by the journey that her death brought.

These are poems of reconciliation, understanding and hope. For McNair, writing about his mother and her family helped him process his grief and learn about his mother and her family in a way he hadn’t known before.

“I had to go to the Ozarks to get to know my mother, even though she lived one state over,” he said.

The poems are fictional but based on his reconnection with his family in Missouri. Ruth Willard left home at a young age. The daughter of cotton pickers, she was old enough to remember the Dust Bowl.

“She couldn’t wait to get out of the Ozarks,” McNair said. “She traveled cross-country with no food or money. She thumbed rides all the way to New England.”

McNair, 73, was named Maine’s poet laureate in March 2011. His term, which expires in 2016, has been marked by several statewide initiatives designed to bring poetry to the people of Maine, especially those outside literary circles. His latest project involves making students aware of poetry around them in mass culture.

It’s unusual for a sitting poet laureate to have time to write. But this family material was “too hot and radioactive” to ignore, he said. He made sense of what he learned at a cabin in the Maine woods.

Much of the year, McNair writes in a rectangular wooden cabin set back above Drury Pond, a tiny, remote lake in Franklin County.

A large window opens to a thick stand of trees and lightly trodden path, which connects the writing cabin to the main camp where McNair and his wife, Diane, spend most of their summer and fall.

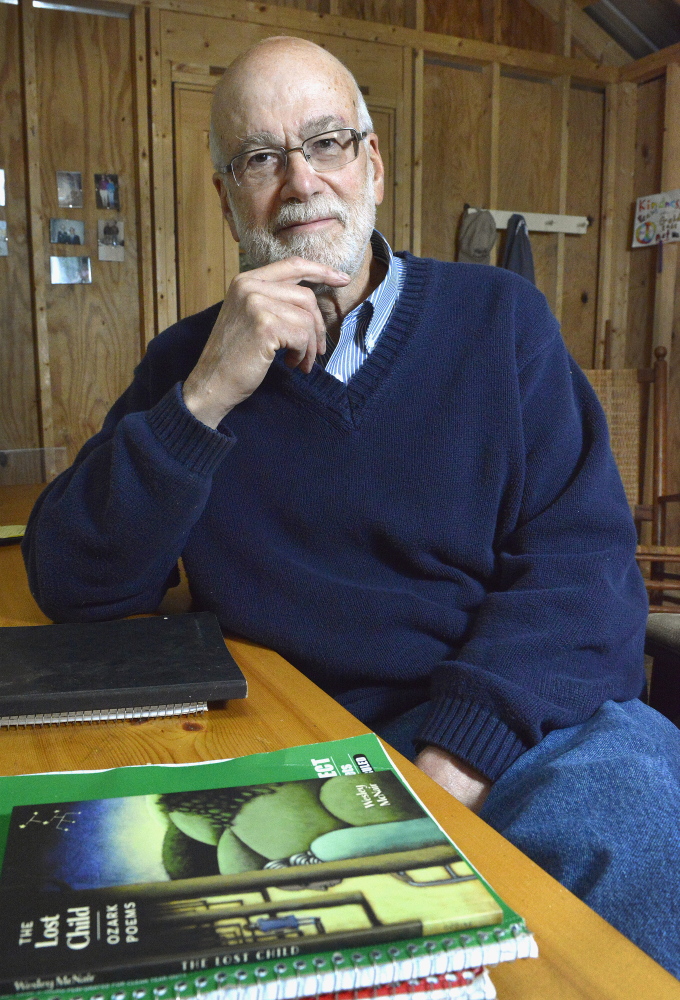

His desk is a wooden slab built into the wall. Its contents are limited to a dictionary and thesaurus, three pens, sticky notes and a few spiral notebooks. The rest of the cabin is equally spartan: Four chairs and a table, a few photos on a wall, a poster announcing a long-ago literary festival on another.

Bookshelves on either side of the desk are mostly bare.

This is where McNair comes for quiet reflection, usually in the early morning and often with his two dogs.

McNair calls this “19th-century quiet,” so far removed he feels from the distractions of daily life.

It was in this quiet place on the side of a lake in the woods of western Maine that McNair conceived and created “The Lost Child.”

When his mother became ill, he reached out to her family, with whom he had a distant relationship. He traveled to a family reunion in 2010 and spent two nights listening to his Aunt Dot tell stories about her sister.

“She stayed up late talking on and on in this beautiful country accent under a dim lamp light,” McNair said. With a Southern accent – “but not a deep Southern accent” – she spoke in flowing sentences that revealed themselves as spoken works of art.

McNair, a man of words, was captivated by his aunt’s stories and how she told them.

“That voice on those two nights became the voice of this book,” he said.

He channeled Aunt Dot during his early-morning sessions. He rose from bed, careful not to wake his sleeping wife, and shuffled up the path to the writing cabin with their two dogs.

As the dogs slumbered on the floor, McNair scribbled out lines, pencil to paper, reflecting on his mother, her family and their lives.

It was hard work, he said. Poetry is always hard work. But writing about family was especially difficult.

“You can’t write poetry all day,” he said. “Poetry requires an intensity of concentration that can wear you out. … I don’t think a poem is worth much if it doesn’t touch a deeper sense that we all have. I always want to get close to that with my writing.”

After writing, McNair made a daily swim across the pond, the dogs paddling alongside. Head down, legs pumping and arms pulling through the water, McNair bathed himself in thoughts of his personal journey from Maine to Missouri.

“The Lost Child” closes with a poem called “Why I Carried My Mother’s Ashes.” It finds the family “taking the gray dust into their old hands” and spreading his mother’s ashes by graves of her parents.

“Because they loved her, as I did in this moment when she seemed to join us, and I no longer missed her,” he writes.

“Because the voice I heard then was my own voice saying a loud Amen, now mixed with their Amens, all of us bound together in this homeplace where I had carried my mother, who would never need to run back to it, or dream of holding their voices to her ear, because she would never, ever again be gone.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story