Ranking high on my list of least-useful questions is the nonetheless common inquiry “What is art?”

That became a conventional query in the 20th century, after pure abstraction erased traditional requirements for skill at mimesis in painting, while the advent of found objects did something similar for sculpture. But the nagging question was soon satisfactorily answered through the wonders of circular reasoning: Art is whatever an artist does.

End of story.

Except, not quite. The useful answer implied its own conundrum: If art is what an artist does, then what is an artist? What, exactly, does one do to become, be and remain one?

“Bruce Nauman: The True Artist,” a new and lavishly produced book from Phaidon, probes the question with wit, insight and a prodigious amount of research, plus a good deal of personal experience. Nauman is among our most significant artists, and author Peter Plagens has been following his work since 1966.

Back in the Middle Ages, artisans and craftsmen pulled themselves out of serfdom through the establishment of guilds, which gave a kind of professional stamp of approval to solve the artist-riddle. Patronage of church, state and aristocracy identified artists for the Renaissance, when they began to act as independent contractors.

The subsequent rise of government-authorized art academies codified the process. But then the modern democratic era overthrew them, stripping the academy of state regulatory power. The question of what an artist is shifted with the destabilizing rumble of slipping tectonic plates. What had been for centuries essentially a practical question became a philosophical one.

Today, art schools and MFA programs are often erroneously seen as a late, tenacious iteration of the old state academy, handing out artist benedictions. (Think of the Scarecrow in “The Wizard of Oz” deciding that he has a powerful brain because a diploma has been awarded.) Answering the question isn’t that simple, as this book shows.

As long as we’re asking questions, here’s another one: Do we really need another Nauman book? Among a handful of the most important and admired artists of the last half-century, he has already been the subject of plenty of writing.

This beautifully produced, profusely illustrated book includes full-page reproductions of Nauman’s work, followed by astute selections of other art for context, plus helpful documentary images. An unusual three-fold hardcover wraps the assembled two-dimensional pictures and text within a sturdy three-dimensional box. (Hence the hefty $125 price tag.) A virtual language-object, the design is Nauman-esque.

Flip to the back, and the bibliography lists scores of predecessors. The 167 items range from essential full-scale monographs to incisive Internet blog posts. Some are career overviews; others concentrate on one of the many materials and processes (drawing, sculpture, neon, film and video, environments, performance) and images (language, animals, self-portraiture, clowns) that he has employed.

Born in Wisconsin, Nauman moved to California in 1965, stayed until 1979 and then went to New Mexico, where he still lives. He has been the subject of roughly 60 international solo museum exhibitions, most also accompanied by publications.

The first was in December 1972, when a retrospective – at the tender age of 31 – opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, traveling to New York’s Whitney Museum the following spring. (Seeing it at the Whitney as an art history graduate student is what confirmed for me a shift in focused study from Renaissance to contemporary art.) Young Nauman was already prolific: The show featured 117 objects, 10 multiples, 18 films and 13 videotapes.

What’s surprising now is that the answer to the question of whether we need yet another big Nauman book turns out to be an emphatic “Yes.” Plagens makes plain that for nearly 50 years, Nauman’s work has repeatedly explored the philosophical question of what an artist is – and expressed radical skepticism about any definitive answer.

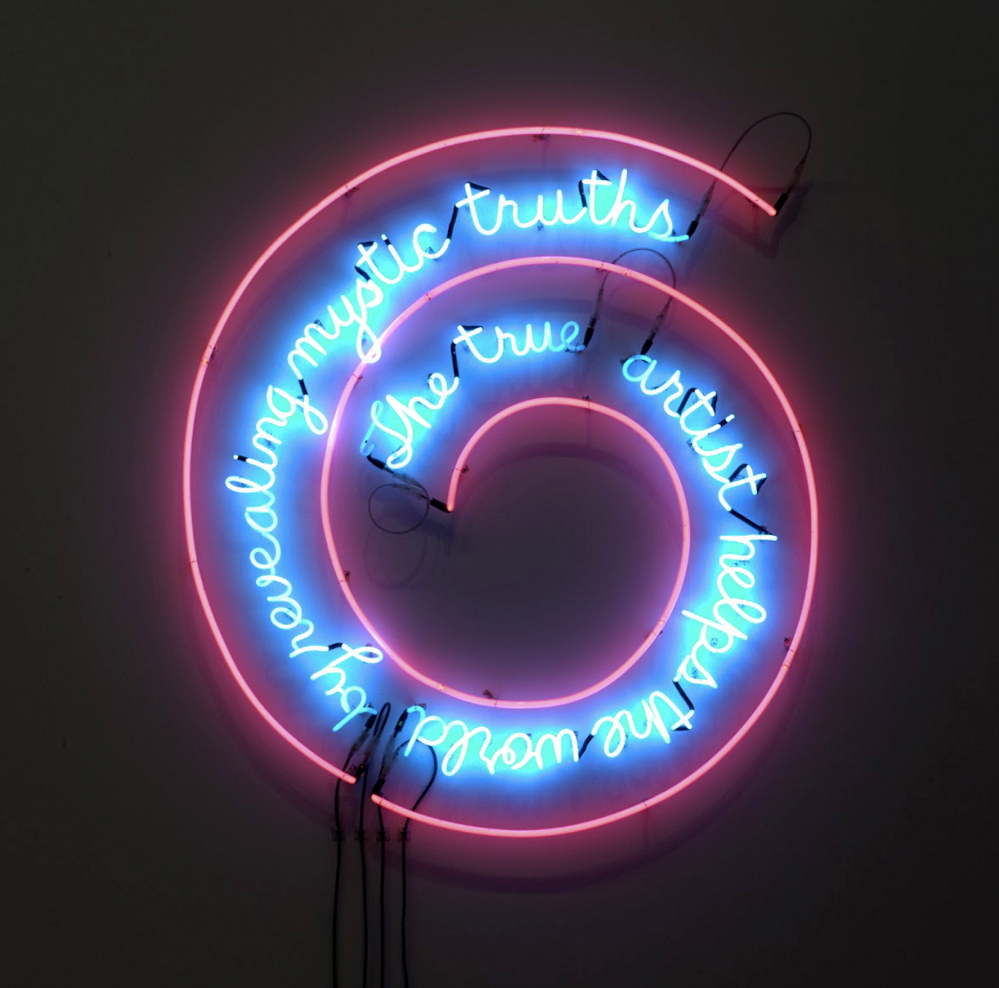

That can drive people crazy. Take the glowing neon sign from which the book gets its title: 1967’s “The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.”

Is the neon sign satire or a statement of faith? Or somehow both?

The romantic artistic claim of mystical revelation is offered up as a straightforward declaration. But the radiant red and blue neon, which spirals like a hypnotic graphic from Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” as if the true artist is circling the drain, casts it in the blunt visual language of street commerce. (Think storefront palm reader.) Nauman’s sincere ambivalence is oddly bracing.

Plagens brings two distinct advantages to his project, which combines critical analysis with biography and even autobiography.

One is a background as a senior writer and art critic for Newsweek magazine from 1989 to 2003. (Full disclosure: I recommended him for the job.) Fourteen years in journalism honed reporting skills, plus writing with clarity and without jargon.

Numerous interviews with Nauman’s associates flesh out important biographical details and, on occasion, correct the record. Multi-disciplinary artist Meredith Monk, for instance, clarifies that a Nauman performance at the Whitney was not in fact his last, as is commonly repeated. The last came at a 1975 performance art festival at UC Santa Barbara.

One or two small errors have also crept into the text. For example, the big neon sign for Earl C. Anthony’s 1920s Packard showroom in downtown L.A. on Flower and 7th streets (not Olympic) is cited as the nation’s first commercial application of the then-new technology; the citation is meant to amplify Nauman’s pioneering use in California of the neon medium. But correction of the apparent urban legend about the Packard sign was published late last year; Plagens’ book was probably on its way to the printer.

The second distinct advantage is that Plagens is himself a well-regarded abstract painter. The question “What is an artist?” is personal.

This yields a fascinating, 288-page public meditation by one artist on the profound significance of another artist – one he has known, if rather casually, since they were studio-neighbors in Pasadena more than 40 years ago, back when Old Town was a crumbling wasteland.

He even appeared in Nauman’s short 1975 film “Pursuit,” which shows a succession of people running on a treadmill as they keep their eyes glued to a sign that said “truth.” Like hamsters on a wheel, they go nowhere – but the effort of going may just be the point.

The book is divided into 14 concise chapters, the longest focusing on the 1972 LACMA retrospective. At the time, Plagens reviewed it negatively in Artforum magazine. (So did William Wilson in The Times and Hilton Kramer in the New York Times.) He is frank about changing his mind, declaring “I was wrong.”

Plagens dives deep into work he has often but not always liked by an artist he has always respected. His insightful, shifting ambivalence echoes Nauman’s own. Together they illuminate what an artist is and what an artist does.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story