BRUNSWICK – At half past noon, Amtrak Downeaster Train 681 pulls into the platform here in Brunswick right on schedule. It discharges its passengers and starts back in the direction of Portland and Boston.

A few hundred yards down the line, however, the empty train pulls onto a siding and draws to a halt. There it waits, its diesel engine idling against the winter cold, for the next five and a half hours.

It’s a scene repeated daily in Brunswick’s rail yard. The popular service — which continues to exceed ridership expectations — sits out much of the day because of traffic conflicts on the line back to Portland, which is owned and used by the PanAm freight railroad. Instead of making three immediate return trips a day to Boston, the Downeaster has two widely spaced departures, plus a late-evening run to reposition the train back in Portland.

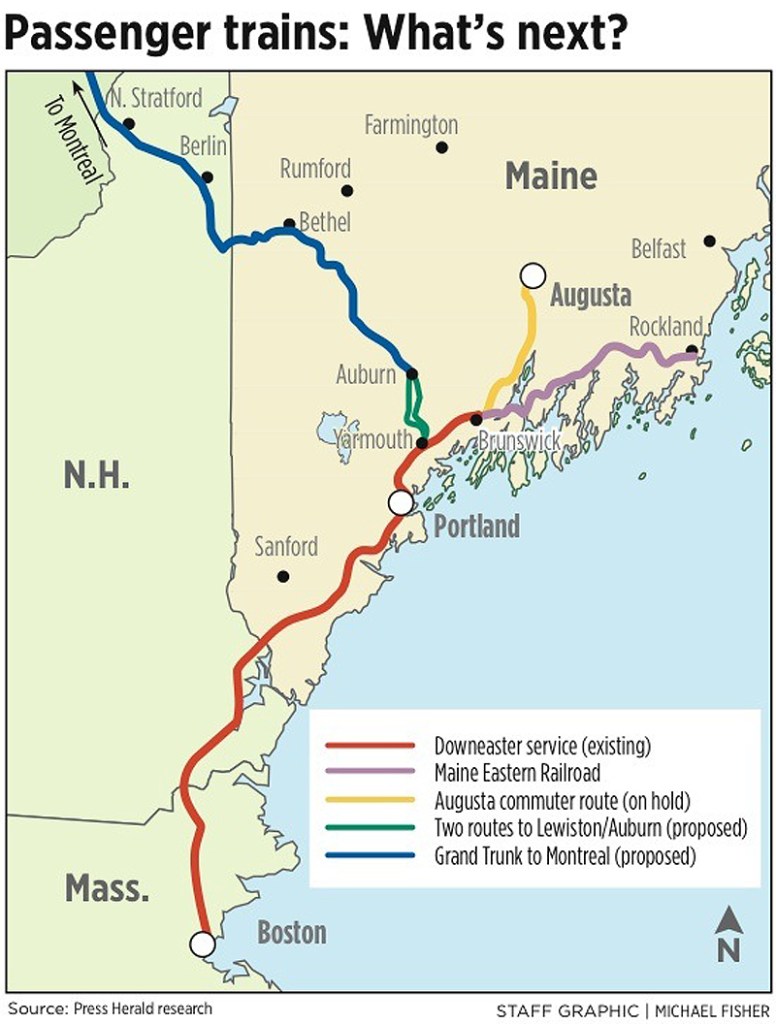

The Downeaster’s expansion to Freeport and Brunswick Nov. 1 — a project decades in the making — has been celebrated by public officials, local businesspeople, and travelers, and fueled excitement that passenger rail might soon return to Augusta, Gardiner, Auburn and other cities.

Ironically, passenger rail service north and east of Brunswick is likely to shrink rather than expand in the months and years ahead because of missing pieces of infrastructure on the Downeaster’s current lines. Until those improvements can be built, allowing the Downeaster to run faster and more frequently between Boston and Brunswick, plans to run connecting commuter trains to Augusta are on hold, and a seasonal service to Bath, Wiscasset and Rockland may be scaled back. Meanwhile, future expansions to Auburn and Montreal may have to take a back seat to making improvements on other parts of the line.

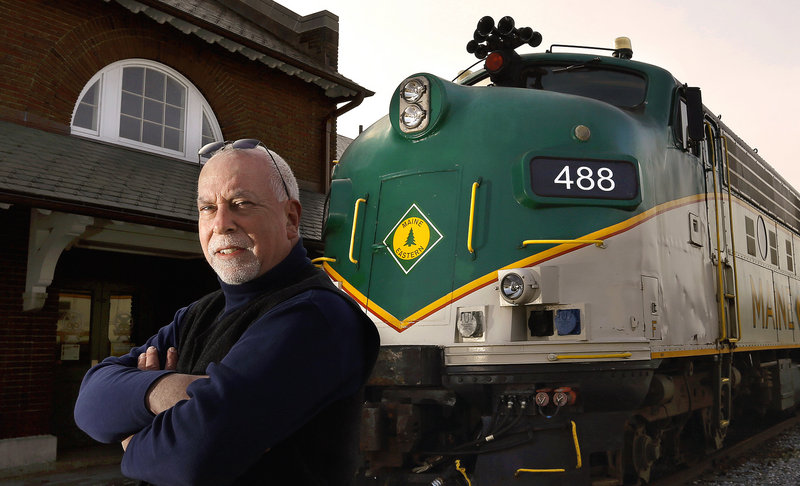

“We weren’t prepared for the limited connection opportunities available with Downeaster’s schedule,” says Gordon Page Sr., director of passenger rail operations for the Maine Eastern Railroad, which owns the lease on the state-owned tracks connecting Brunswick with Rockland and Augusta. The current schedule makes it impossible to get his Rockland passengers onto a morning or midday train to Boston, and his company is considering reducing its seasonal service between Brunswick and Rockland from two round-trips to one.

“It’s unfortunate that when the Downeaster has expanded service to Brunswick, we’re considering having to reduce service,” says Page, whose company’s lease on the tracks in question runs out at the end of the year. “The Augusta issue is on the back burner.”

TO ROCKLAND OR AUGUSTA?

The problem boils down to three missing pieces of infrastructure:

• $9 million worth of passing tracks in Yarmouth to avoid conflicts with the freight trains that run on the route;

• a $12 million “Y” track in Portland that would allow trains to turn directly onto the Brunswick line, saving 10 minutes spent driving to a junction in the opposite direction;

• and a heated $11 million layover building in Brunswick’s rail yard where trains could be cleaned, maintained and sheltered overnight.

“It’s not what we asked for,” says Wayne Davis, chairman of Train Riders/Northeast, the advocacy group that has championed the cause of passenger rail in Maine since 1989. “We’ll suffer through what we’ve got for the winter, but we don’t see what we have as success” for the Brunswick extension, which also serves Freeport.

The Portland-based Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority, the quasi-state agency that runs the Downeaster, applied for a $25 million U.S. Department of Transportation grant last year that would have allowed the projects to go forward, but they were beaten by rival expansion projects elsewhere in the country. For practical purposes, the federal government is the only foreseeable source of major funding, so the project must wait for another federal grant opportunity to surface.

“It’s difficult for me to give any kind of timeline on anything because the situation in the state and federal government at this time makes it questionable in terms of what the opportunities will be,” says the authority’s executive director, Patricia Quinn. “As with the expansion to Brunswick, we try to have the work ready so that when there is a grant we can pull the project off the shelf and immediately get it running.”

Until such a time, the authority’s board decided to run two Brunswick-to-Boston round-trips each day rather than no service at all. The long Brunswick layover — rather than a quick turnaround — was selected because it would allow Bostonians to make day trips to shop in Freeport, a major boon for the town’s retailers. “With just one train set, they’ve managed to make the business community a little happier than they would have been,” Davis says.

There’s also been opposition to the construction of the $11 million Brunswick layover facility from residents of nearby neighborhoods, which Davis has found exasperating. “The site is a rail yard and it has been for 130 years,” he says. “It’s not like this is a new site or idea.”

NORTH TO AUBURN AND MONTREAL?

Extending service in another direction — from the Portland terminal near outer Congress Street to Lewiston-Auburn — also can’t go forward without the construction of the Y track in Portland and the sidings in Yarmouth, where the junctions to both lines to Lewiston-Auburn are located. The Portland terminal would also need to be expanded to allow more than one train to be in the station at a time.

Auburn has long been the next goal for the Downeaster, in part because the tracks have already been upgraded as far as Yarmouth, just 20 miles short of the proposed Auburn Intermodal Passenger Center, where shuttle buses to downtown Lewiston would depart. Another attraction is that it would get Amtrak that much closer to Montreal on the legendary Grand Trunk, the railway that made Portland into the winter port of Victorian-era Canada and helped introduce the Quebecois to the sands of Old Orchard Beach.

“You have 4 million people in Montreal and 4 million in Boston and the Portland-to-Bethel corridor in between them; that shouts opportunity,” says Auburn Mayor Jonathan LaBonte. “That’s already a viable freight line, so any investment improvements would improve freight capacities into the state as well.”

Both intercity rail expansions would require a lot of money, however, and a 2011 Maine Department of Transportation study suggests ridership would be limited.

Running three round-trips a day between Auburn and Portland on the Downeaster was estimated to require at least $107 million in upfront investments — including a new train set — and a $2.5 million annual operating subsidy. The study predicted 30,000 people would use it annually. Running the trains directly to Boston would more than double the cost while boosting ridership only to 45,800.

“Whereas it would be fun to have an intercity train that runs three times a day from Portland, that’s not going to help,” says LaBonte, who is most interested in connecting Lewiston-Auburn with commuter job opportunities in Portland. “In terms of where we can invest best for the dollar, I can help more people get access to jobs with a bus than with either an intercity or a commuter train.”

COMMUTER TRAINS INSTEAD?

But Freeport Town Councilor Kristina Egan, former director of the South Coast Rail commuter project in Massachusetts, says commuter trains may provide a cost-effective alternative to buses moving commuters between Portland, Westbrook, South Portland and Lewiston-Auburn. Rather than using heavy passenger trains, the system might use self-propelled rail cars called Diesel Multiple Units that allow for more frequent and cost-effective service.

“The most expensive piece of getting a rail line ready is having a right-of-way. We already have a right-of-way in and around Portland,” Egan says. “DMUs are more reliable than buses, carry more people, and are more attractive and comfortable.”

One enthusiast of these self-propelled rail cars is touting a proposal that would establish service between Portland and Lewiston with or without the Downeaster’s improvements. Tony Donovan of the Maine Rail Transit Coalition would take a different route into Portland, following the old Grand Trunk line from Yarmouth, which crosses the old trestle bridge beside Portland’s B&M Baked Bean plant, and skirts the East End shore on the route currently used by the Maine Narrow Gauge Railway. The service would terminate at its own station on the city’s eastern waterfront, not far from where the old Grand Trunk Terminal stood until 1966, when it was demolished to make way for a parking lot.

“The next rail service in Maine will be between India Street in Portland and Auburn, followed quickly by connections to the communities of Oxford County,” Donovan says. “And it will not only pay for itself, it will bring renewed prosperity to the communities along the corridor region.”

Last month, Portland city councilors directed city staff to renew studying the feasibility of both bus and rail commuter links to Lewiston-Auburn. The three cities are expected to apply for funding from the Federal Transit Administration to pay for the study.

CANADIAN RAIL IN CRISIS

Getting Amtrak from Portland to Montreal is a much longer and more expensive prospect. The 2011 DOT study examined the feasibility of running two daily round-trips, with stops in Auburn, South Paris and Bethel; Berlin and North Stratford, N.H.; and Sherbrooke, St. Hyacinthe and St. Lambert, Quebec. Construction costs would range from $676 million to $899 million and would require an estimated annual subsidy of $16 million to $18 million based on expected annual ridership of 200,000.

It would also be competing with a shorter and less expensive route from Boston via Burlington, Vt. Amtrak already has service as far as the northern Vermont town of St. Albans, and ran trains on to Montreal as recently as 1995. The last passenger train from Portland to Montreal pulled out of town in 1967.

“The Vermont corridor is favored right now (by federal authorities) as far as connecting Boston,” says Nate Moulton, director of the rail program at the Maine DOT. “The question is if we can drive more ridership from Montreal because of destinations in Maine like Sunday River, Old Orchard Beach and Portland.”

There’s likely to be little initial support from the Canadian side, according to Ontario-based passenger rail advocate Paul Langdon. “Passenger rail in Canada is at a crisis right now, and (Ottawa) just announced more cuts to the lines that are left,” he says, noting that daily service was recently eliminated to the Maritime provinces and scaled back even in densely populated southern Ontario. “With the government of (Conservative Prime Minister) Stephen Harper it’s kind of doom and gloom, but I don’t think you should stop having a vision.”

WORTH THE INVESTMENT?

The Canadian leader isn’t the only one who thinks passenger rail isn’t worth the cost. Charles Arlinghaus, president of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy in Concord, N.H., has been fighting against a proposed Downeaster-like train service connecting New Hampshire’s capital with Boston. “Trains have a very large capital investment cost that could be spent on something else — fixing buildings or energy efficiency,” he says. “Buses can cover their capital and operating costs and yet perform the same services as trains do.”

Passenger trains, Arlinghaus says, make more sense in major urban areas. “It would be hard for New York City to exist without trains, but it would be easy for Montana,” he says. “Both our states are a lot more like Montana.”

Surprisingly, statistics show that the Downeaster currently comes closer to paying for itself than the Big Apple’s heavily used commuter trains. Passenger fares cover 60 percent of the Downeaster’s costs, compared to 59 percent for Metro-North (which connects Manhattan with southern Connecticut and Westchester County) or 49 percent for the Long Island Rail Road. The rest of the Downeaster’s costs are covered by federal funds (about $8 million a year) and the state government (another $1.2 million).

But Quinn at the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority says passenger rail’s real advantage is as an economic development tool, prompting real estate developments and attracting businesses while reducing road congestion.

In 2004, when the Downeaster had fewer destinations and departures, the Maine DOT found it was responsible for $15 million in economic activity in Maine and New Hampshire alone, more than twice its public subsidy at the time. Since then, it helped prompt an $80 million mixed-use development near the Saco station, a $20 million condo project at Old Orchard Beach, and a $30 million hotel complex in Brunswick. The train also is expected to generate more than $2 million in additional Maine tax revenue this year.

“You get more than transportation from A to B,” Quinn says. “It’s helped revitalize communities, create more jobs and improve the quality of life, and it’s also the most environmentally friendly form of transportation. It’s an economic engine for the region.”

But for now, the authority is focused on getting the existing Boston-Brunswick service up to snuff, making the pitch for new tracks, signals and other infrastructure in all three of the states it passes through. The goal: seven round-trips from Boston to Portland, with up to five going on to Brunswick.

“We have to take care of the core service first,” Davis says. “Everything else builds on that.”

Staff Writer Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story