It makes sense that Harvard is mounting a major centennial celebration of the Bauhaus. The founder of the German art school, architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969), took over the architecture program at Harvard in the late 1930s after the Nazis’ pressure to shut the Bauhaus down.

But it also makes sense that Bowdoin College would mount a show. James Bowdoin founded the first college art collection in America intended for teaching. Bowdoin’s “Modernism for All: Bauhaus at 100” is student-curated, and it’s only stronger for sitting alongside the student-curated “Among Women” and a historic look at Bowdoin’s teaching collection, “To Instruct and Delight,” led by works by Italian masters and notable portraits by Gilbert Stuart of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Bowdoin and his wife. Set in the Beaux-Arts gem of a museum designed by the leading American architect of the day, Charles McKim, the modernist impulses of the Bauhaus are only more apparent.

“Prellerhaus Balconies, Bauhaus Dessau,” 1933, gelatin silver print, by Gerd Balzer, German, 1909-1985. Museum Purchase, Lloyd O. and Marjorie Strong Coulter Fund, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Gropius founded the Bauhaus (meaning “build-house” in German) in Weimar in 1919 and remained the director until 1928. The school moved to Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and to Berlin from 1932 to 1933 under director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The school was in operation only until 1933, but its mission, messaging and related artists and architects had a massive influence on art and design culture of the 20th century.

In contrast to the rich aesthetic and ornamentation of the previous centuries (McKim’s museum, based on a famous Italian palazzo, is a great example), Bauhaus followed the phrase attributed to Frank Lloyd Wright’s teacher, the great American architect Louis Sullivan: “form follows function.” (And, yes, Wright himself is directly related to this brand of modernism: His 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio produced in Germany is seen as a foundational point of the International Style, the dominant architectural style of straight lines, pristine exteriors and an aesthetic of crystalline clarity.)

While it may appear as minimalist and aesthetically exotic, the Bauhaus aesthetic is surprisingly pervasive even in contemporary American life. Metal tube furniture, for example, was invented by Marcel Breuer as part of Bauhaus. Sure, the famous Breuer chair, a boxy but reclining chair featuring leather stretched across a tubular frame, has a swanky reputation, but metal tube furniture, such as nesting tables and stools, are seen more as common than collectable. Inspired by bicycle frames, a chair and table by Breuer anchor the center of the show. (Breuer taught at Harvard with Gropius and several of their buildings can be seen in Greater Boston.)

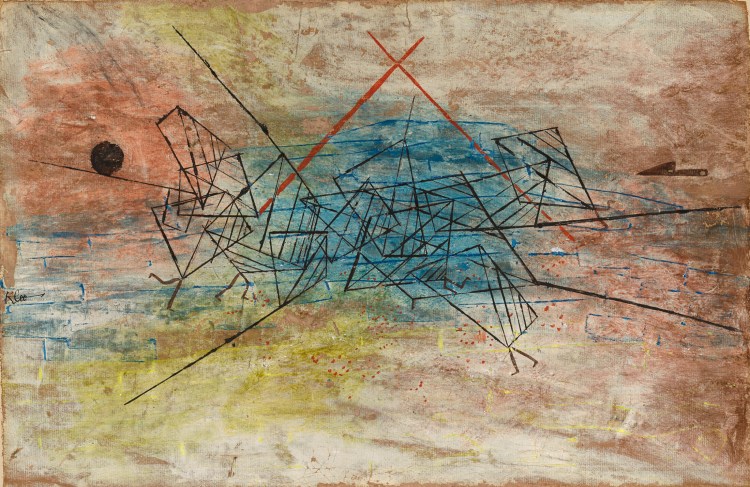

While many of the students of Bauhaus haven’t accomplished household name status, the faculty comprised an all-star team. “Modernism for All” includes a portfolio of 12 prints that Professor Wassily Kandinsky – a seminal Russian abstractionist – gave to Gropius as a birthday present. A suite of prints by American/German Lyonel Feininger, the first member to join the Bauhaus faculty, reveals not only Feininger’s spritely cubist style, but his metaphorical adherence to the principles of Bauhaus. One of the most exciting works in the show is a painting by the playful Swiss artist Paul Klee: It’s a battle between geometric lattices with legs. You can take the sprayed blood to mean this is a scene of violence, or like I do, you can see it as the ironical play of artistic styles and personalities as more of a metaphorical field of aesthetic conflict.

The German Oskar Schlemmer’s paintings always struck me as unappealingly severe, but his pair of cast-metal sculptural works and a performance poster reveal pleasing organic qualities within his precisionist style.

Gropius himself is represented by several objects, including a pair of lithographs of his design for a monument to the “March Dead.” While he personally sought to keep his students from making public political statements, this is an emotionally charged expressionist design for a moment to Socialist strikers who were killed by the state apparatus. These represent an anomaly, but they help humanize Gropius.

For a small space, it’s a big show with a great deal of worthy information. “Modernism for All” also features about 20 photographs, including many by Feininger’s son, T. Lux Feininger, whose work shifts between documentation of the school and a few impressively artful images. Particularly notable is a print by German photographer Grete Stern. Her 1931 “Paper in Glass” features an incised glass of water with some crumpled paper elements with it. It is set on a backdrop of graph paper, but the effect of the image is more optical aesthetics and textured chiaroscuro (light/dark) than anything measurable.

“The Cathedral,” 1919, printed c. 1964, woodcut, by Lyonel Feininger, German, 1871–1956. Gift of David P. Becker ’70, Bowdoin College Museum of Art

What Bauhaus did best, however, were objects, and the show, however small, is not lacking. An elegant chess set by German Josef Hartwig features bishops and knights in forms that lay out their movement logic. Two coffee makers and two cups reveal a range in design. Marks’ and Wagenfeld’s double-chambered “Sintrax” clear glass coffee maker is fascinating to consider; it’s a functional rebus, and it’s particularly satisfying when you figure out how the vacuum system works. One of the most elegant “sculptures” is a door handle by Gropius. Its presentation in a small block of wood gives it the look of a (excellent) work of art.

And that is the crux of Bauhaus and its extraordinarily influential echoes within Western culture. In America, for example, we still have a divide between folks who value craft, design and functionality and those who believe art needs to remain in the aesthetic realm (e.g., those who believe painting is the “highest” art). Bauhaus sought to dissolve hierarchical distinctions among architecture, design, art and craft (a mode of thinking to which I subscribe). If you gather 10 art historians in a room, you are likely to get 10 completely different definitions of “Modernism.” America’s most towering art critic, Clement Greenberg, saw artistic modernism as an essentialist model which had painting, for example, pushing ever-closer toward its defining elements of flatness and the “opticality” of paint on its wall-mounted support. My take is that modernism has always been a revolutionary impulse that sets out to question any dominating aesthetic and cultural assumptions. Insofar as previous European culture (specifically academic and institutional models) had artists building upon the foundations and accomplishments of earlier generations, this version of modernism is also progressive, but it is self-aware and self-critical – and therefore, potentially subversive – to its core because the propriety of the past is not taken for granted.

The fact that we can so clearly celebrate Bauhaus at 100 while we couldn’t, as a culture, come to terms with the centennial of abstract painting as a broad cultural phenomenon just a few years ago is telling. (I think it’s a sign that we’re still overly caught up in “isms” and institutions.) Bauhaus, however, represents a great opportunity for us to reconsider our cultural past and sources. We should start with a few questions, such as, why did Hitler’s right-wing party seek to shut down the Bauhaus and ban abstract painting as “degenerate art?” Shows like “Modernism for All” are good reminders that there is a lot of important art to consider and that we still have much to talk about: We are not out of the woods yet.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story