Woodie Garber was the kind of parent who would tell his enraptured child to close her eyes, and then place a stone in her hand and ask her to guess its color. He was also the kind of parent who got depressed and stayed in bed for weeks. He was authoritarian, verbally abusive, a racist, and a bully with no clear body boundaries, and he was a star in the world of modern architecture. In other words, Woodie Garber would make a good subject for a book – and he does.

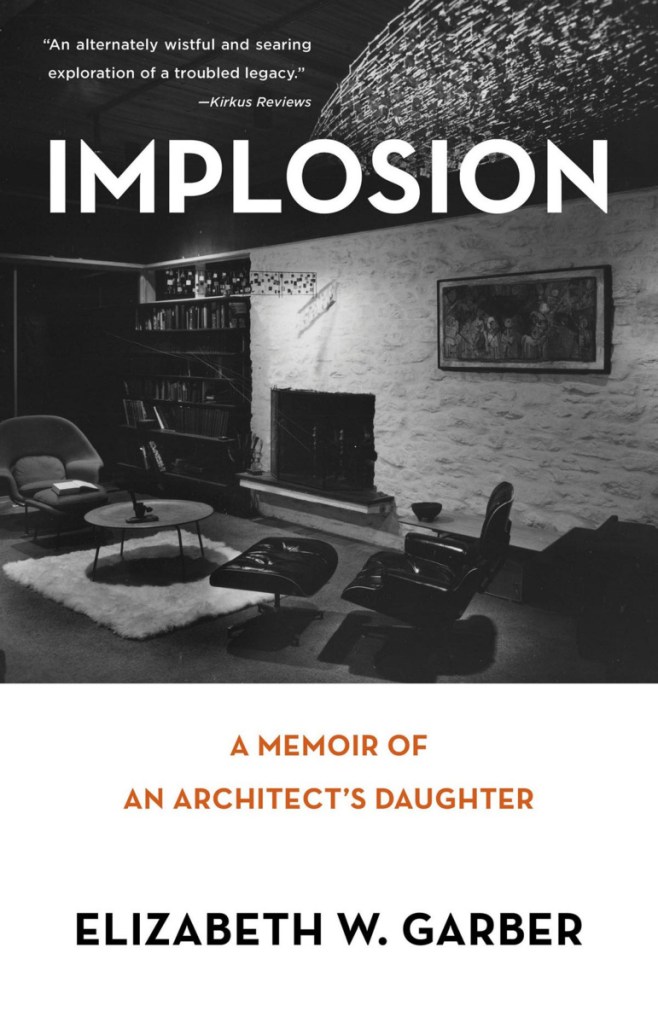

In “Implosion: A Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter,” Elizabeth W. Garber, a poet and acupuncturist based in Maine’s midcoast, walks the reader through her Cincinnati childhood, spent largely in a glass house of her father’s design and partly of his and his family’s making. “Remember, this is fun!” Woodie tells his three blistered, sandpaper-wielding children. “You’ll remember this for the rest of your lives and you’ll be grateful.” He’s half right.

Young Garber knows that it’s not just the glass house that makes her family different: her father forbids prefab food at the table, is known to answer the door naked but for a Time magazine fig leaf, and has his daughter disrobe for nude massages – no fig leaf – into her teens.

As Garber shares childhood memories intercut with black-and-white photos, she tracks the progress on what should be her father’s career-defining creation: the University of Cincinnati has commissioned him to build a high-rise dorm that will be the city’s first mirror-glass tower. Someone watching the construction of Sander Hall in young Garber’s presence says that it looks like a “big prison” made up of “concrete cells,” which wounds her: Garber believes in her father’s artistic vision. The building’s ultimate fate is reflected in her book’s title.

Much of “Implosion” plays out in the late ’60s and early ’70s, as the counterculture, forgoing a helmet, rides roughshod over tradition. Its newfangled ideas manage to permeate even the walls of the glass house, through which Woodie Garber’s hypocrisy becomes visible. “The modernist radical would now pit himself against the new revolutionaries, blacks fighting for jobs and justice, women fighting for their voice, and long-haired anti-war protesters setting out to bring down the old order,” Garber writes. “He did not realize he was pitting himself against his own wife and children who, almost inevitably, each in their own way, would be joining the revolution.”

There’s a bit too much telegraphing of this sort in “Implosion,” as if the author senses that her story hasn’t yet built up a head of steam; “Hang in there,” she seems to be telling the reader. Until Garber’s book finds its shape at around the halfway mark, when she recounts falling in love with a black high school classmate and her father’s efforts to keep them apart, “Implosion” reads like a collection of scenes. As a teenager trying to keep up with the day’s fashions, Garber was a whiz with her sewing machine, and she might have brought her tailoring skills to bear on her early chapters. But as “Implosion” gets rolling, Garber proves that some people who live in glass houses really should throw stones, and when her aim is good, it’s shattering.

Nell Beram, co-author of “Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies,” has recently written for the New York Times Book Review and L’Officiel.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story