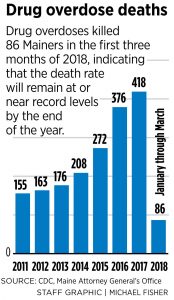

The number of people killed by drug overdoses in Maine during the first three months of the year fell slightly from last year, state authorities said Friday, although deaths caused by Maine’s ongoing opioid crisis are still near all-time highs.

From January through March, 86 people died of overdoses, down from 89 such deaths during the same time period in 2017, according to the Maine Attorney General and Medical Examiner’s offices. A record 418 people died of drug overdoses in 2017. More people now die from drug overdoses than motor vehicle accidents, according to federal statistics.

From January through March, 86 people died of overdoses, down from 89 such deaths during the same time period in 2017, according to the Maine Attorney General and Medical Examiner’s offices. A record 418 people died of drug overdoses in 2017. More people now die from drug overdoses than motor vehicle accidents, according to federal statistics.

Although the total number of deaths declined during the first three months of 2018, more people who die from overdoses were killed by illegal substances, including fentanyl, as opposed to pharmaceutical opioids.

About 65 percent of the deaths recorded in the first quarter were due to fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, up from 52 percent in 2016 and 59 percent in 2017. Fentanyl is a cheaper, more powerful alternative to heroin, and many users who believe they are taking heroin are actually using fentanyl.

“The shift we are seeing from heroin to cheap, deadly fentanyl is deeply troubling,” Attorney General Janet Mills said in a statement. Mills, one of seven Democratic candidates for governor, oversees the medical examiner’s office.

“We must break the stranglehold that opioid use has on our state,” she said. “The figures released today demonstrate dramatically that we have not yet turned the tide against opioids and there is still much work to be done.”

Addiction experts denounced the state’s anemic response to the opioid crisis.

“This is sad, sad, sad,” said Dr. Lisa Letourneau, associate medical director of Maine Quality Counts, a health advocacy nonprofit and a former member of the state’s opioid task force. “The state is failing to respond appropriately to this epidemic. We need doubly accelerated strategies. We are not doing enough.”

One proven tool for reducing overdose deaths is finally becoming more widely available in Maine. The Board of Pharmacy last week published new rules for making naloxone, a lifesaving drug that reverses the effects of an overdose, available without a prescription. Republican Gov. Paul LePage had repeatedly vetoed bills to expand access to naloxone, sold under the brand name Narcan, and slowed down the administrative rulemaking process. But the Legislature finally mustered the votes needed to override his opposition and provide access to naloxone for anyone.

A bill that would provide $6.6 million to help about 500 uninsured Mainers gain access to substance use disorder treatment is in limbo, as the Legislature adjourned this spring before deciding whether to fund that bill and others. The Legislature may return in a special session, but the fate of the bill is unclear.

Meanwhile, expanding Medicaid would provide access to treatment for about 70,000 Mainers, although it’s unclear how many of those newly eligible for coverage would need treatment. Maine voters approved Medicaid expansion 59 percent to 41 percent in 2017, but implementing the expansion is on hold.

LePage and House Republicans have been refusing to expand Medicaid, arguing that the Legislature needs to appropriate money for it, while Democrats say there doesn’t need to be a specific appropriation. An advocacy group is suing the LePage administration, saying Mainers should be able to sign up by July 1.

Malory Shaughnessy, executive director of the Alliance for Addiction and Mental Health Services, said that while efforts to help alleviate the opioid crisis stall, Mainers are dying.

“Things have not gotten any better,” she said. “It’s a travesty.”

The Legislature did approve a bill in 2016 that placed more restrictions on prescribing opioids, and opioid prescribing dropped 32 percent from 2013 to 2017, in part because of the new law and also because of changes in prescribing practices and Medicaid rules in Maine that also constricted opioid prescribing.

Dr. Mark Publicker, an addiction treatment specialist and past president of the Northern New England Society of Addiction Medicine, said the state has had limited success in increasing the number of doctors who are certified to prescribe Suboxone, a leading medication used to treat opioid use disorder. But Publicker said demand for treatment still far outstrips the supply, and the new prescribing law may be having the unintended consequence of pushing more people into illicit drug use. The law sets caps on dosage and length of opioid prescriptions, although there are many exceptions, such as end-of-life care.

“There’s lots of people dying still. It’s a tragic and terrible situation,” Publicker said.

Mills urged more treatment, education and prevention efforts, and called on the Legislature to act on the issues.

According to Maine DHHS, 8,627 Mainers received medication-assisted treatment, including methadone and Suboxone, in 2016, the latest year figures were available.

While there’s no estimate of how many Mainers lack access to opioid treatment, a U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration survey estimates about 25,000 Mainers struggling with all forms of drug addictions believe they don’t have access to treatment programs.

The figures released were compiled by Dr. Marcella Sorg of the University of Maine’s Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center.

In all of 2017, 418 people died of drug-related causes. In 2016, that figure was 376 deaths—many of which were chronicled in a Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram series, Lost: Heroin’s Killer Grip on Maine’s People.

Joe Lawlor can be contacted at 791-6376 or at:

jlawlor@pressherald.com

Twitter: joelawlorph

Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

Comments are no longer available on this story