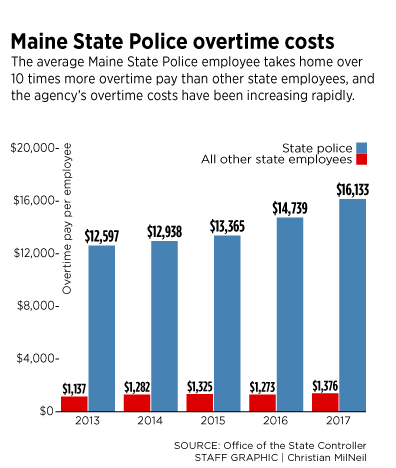

Maine State Police overtime has increased by nearly 30 percent over the last five years and those extra hours appear to be more heavily concentrated than ever before, according to an analysis of state payroll data.

The average overtime pay per state police employee was $16,133 last year, up from $12,597 per employee in 2013. Some, though, are making significantly more. In 2017, 27 state police workers made at least $40,000 in overtime, led by Sgt. Thomas Pappas, who earned $97,242 in overtime on top of his $70,268 salary. Just two years earlier, only seven earned more than $40,000 in overtime.

The number of employees who exceeded $20,000 in overtime last year – 107, or nearly 1 in 5 – is up from 75 who made that much two years earlier.

Lt. Col. John Cote, nominated by Gov. Paul LePage this month to head the state police, said the added overtime can be attributed to many things: More demands for specialized units such as bomb squads and crisis negotiation teams, special details that request police presence, such as construction zones and escorts, and covering for vacancies within the department.

“Our specialty teams serve a specific and special role as they are the safety net for many communities and agencies when a robust, resource-intensive, specialized-skill-set response is required,” Cote said in a written response to questions from the Maine Sunday Telegram.

Part of the overtime cost increase is driven by base wage increases within the department. Since overtime is paid at 1.5 times, when the base wage goes up the overtime rate does as well.

In many cases, Cote said, overtime is reimbursed, either through grant funds or contracts, which means it doesn’t cost taxpayers. But he said he didn’t know how much overtime was reimbursed in 2017 because he hadn’t reviewed the budget figures.

Within the last year, several major metropolitan police departments, including Boston, Chicago, Detroit and Nashville have dealt with massive and sometimes unexplained increases in overtime costs, leading to calls for reform.

Compared to those cities, Maine’s situation is not as dramatic, but costs are still trending steadily upward. In 2013, state police employees made $4.36 million in overtime. Last year, it was $5.61 million.

Overtime among all state employees increased during that same time by 17 percent – compared to a cumulative inflation rate of 5.5 percent – but the increase in the Department of Public Safety, which includes state police, accounted for 32 percent of the total, even though the department’s 669 employees represent about 4 percent of the state workforce.

Maria Haberfeld, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said overtime is often viewed as a “necessary evil” in policing, but that doesn’t mean problems can’t arise.

“There is a feeling that police officers should be mindful of working a lot of overtime because it’s such a nerve-racking profession already,” she said. Haberfeld pointed out that pilots, truckers and some health professionals have strict limits on overtime, yet police do not.

Fatigue in any profession can lead to lapses in judgment and slow response, but that’s even more pronounced in a profession like police, Haberfeld said.

Cote said employees, with the exception of supervisors and some others, have the same opportunities for overtime. Some simply work more.

“We do monitor our members and have work rules in place to help mitigate the impact of scheduled overtime,” he said. “Exigent circumstances can be hard to adjust to, as a crisis can result in officers working beyond their scheduled hours.”

Aaron Turcotte, past president of the Maine State Troopers Association union, said he believes there are safeguards in place.

“I think we do a good job knowing the capabilities of our troopers,” he said. “We don’t want our people out there tired.”

‘STAFFING IS ALWAYS AN ISSUE’

In 2016, LePage signed a law that increased trooper pay between 13 percent and 18 percent, depending on rank and title.

The troopers’ union already had negotiated a 3 percent raise in September 2015 and another 3 percent raise in July 2016 as part of their contract that ran from 2015-2017.

As those salaries went up, so too did the overtime, since it was calculated at a higher level. The starting salary for a trooper is $46,904.

The pay increases were meant, in part, to help attract and retain employees, something the Maine State Police have struggled with, although not nearly as much as some other public safety agencies.

“Staffing is always an issue,” said Turcotte, who was promoted in January to sergeant for Troop A in York County. “We don’t have a major shortage right now, but like any other law enforcement agency, we have issues with attracting and retaining people and we’re required to do more all the time.”

Cote said there are 14 current vacancies, down from 36 two years ago.

In other areas where overtime has exploded, staff shortages are often to blame.

The city of Detroit saw overtime for police officers jump 136 percent, from $16.9 million in 2013 to $40 million in 2017. Nineteen officers made more than 50 percent of their base pay in overtime.

Detroit Police Chief James Craig, who was Portland’s police chief for two years in 2010-11, told the Detroit News last month that his department needed to manage its overtime better.

Other cities have cited special details, where departments get reimbursed, as the main reason behind more overtime.

In Nashville, the police department’s overtime budget increased from $6.1 million in 2014 to $9.1 million last year, the Tennessean reported this month. Officials attributed the bump to more requests for uniformed officers to staff festivals and sporting events.

The Boston Globe reported in February that the city’s police overtime costs went up by $6 million in 2017, largely because of increased staffing at events like the New England Patriots’ Super Bowl victory parade, the Women’s March and others.

‘A LOT COULD GO WRONG’

Some agencies have not been able to explain their increases.

Last year, the inspector general for the city of Chicago released a critical report on the police department’s use of overtime – concluding that the system can be easily abused and created the risk of having tired officers on duty.

From 2011 through 2016, the department increased its overtime budget from $42 million to $146 million – 248 percent.

The department defended itself, even as the inspector general highlighted that $27.6 million in overtime from 2014 through mid-2016 had no record of authorization, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Cote said operational overtime within the Maine State Police has not exceeded what is budgeted, and he believes time is well-managed.

He and Turcotte also said that overtime is offered on an equal basis to everyone, with senior officers getting first dibs, but it’s often the same people taking each overtime opportunity.

High concentration of overtime was one of the findings of a report last fall in Governing magazine that said “a small but growing body of research links long hours and officer fatigue to a host of public safety issues.”

The most recent Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics survey found that only one-third of agencies reported limiting overtime hours.

Karen Amendola, the Police Foundation’s chief behavioral scientist, told the magazine that’s a big problem.

“If you put a lot of tired cops into a very sensitive situation, a lot could go wrong,” she said.

Pappas, the state police sergeant and top overtime earner in Maine last year, would have had to work an average of 36 overtime hours every week to earn the $97,242 in overtime pay recorded for him in 2017. That’s based on an hourly rate of $50.67, which is one and a half times the hourly rate for his base rate of $33.78.

Pappas did not respond to a request for comment about his overtime, but Cote said the sergeant spent part of 2017 assisting a task force “targeting high intensity drug trafficking areas.”

Haberfeld, the John Jay professor, said limits should be a part of the conversation for police departments, but she acknowledged that police officers will always have unpredictable schedules.

Although it’s not a direct comparison, the Portland Police Department had 243 employees on the payroll last year. Only six made more than $20,000 in overtime, according to data from the city.

THE PENSION CONNECTION

Twenty and 30 years ago, overtime was seen as a way for senior state police employees to increase their pensions, according to Peter Mills, executive director of the Maine Turnpike Authority.

He knows because the state police have a troop dedicated to patrolling the turnpike.

“The financial incentives are built into the system,” Mills said. “It’s fifth-grade arithmetic.”

State employee retirement earnings are calculated using the average of the employee’s three highest annual salaries, so adding, say, $50,000 in overtime to a base salary for a few years can make a big difference.

That’s harder to do now.

In 1999, a law was passed that capped salary increases for pension purposes at 5 percent a year or 10 percent for a three-year period. A state police trooper can still work as much overtime as he or she wants, but when it comes time to applying the extra wages to a pension, there are limits.

“We are aware of the impact overtime can have on retirement; however, we must also meet the demands for service as circumstances present themselves,” Cote said.

Turcotte said if state police are working extra to add a little to their pension, he doesn’t see that as a scandal. He said overtime isn’t driven by troopers but by services.

“If someone chooses to work longer hours, that’s their prerogative. That’s a choice they make,” he said. “There are sacrifices that come with working overtime, too.”

Turcotte made $29,090 in overtime last year on top of his $65,084 salary.

Mills said he has noticed overtime costs increase for troopers that contract with his agency. In most cases, the troopers provide traffic control in construction zones but their pay is reimbursed by the turnpike.

“I think the contractors and maintenance people would be happy to have them out there every time, but we have to exercise some judgment,” he said.

Over the last three years, many of the same names show up on the list of high earners. Pappas, Trooper Lee Vanadestine, Trooper John Davis, Sgt. Alden Bustard and Trooper Adam Stoutamayer have each made $50,000 on top of their regular weekly wages every year.

Some of the top overtime earners are clearly well-respected police.

Pappas was named Trooper of the Year in 2010.

Scott Bryant, another big overtime earner, took home that honor in 2014.

Turcotte said whenever managers look at increases in overtime, the question becomes: At what point do we hire more officers?

“But it’s often much cheaper for a department to pay out overtime than to hire new people, who have to go through training and who will get a benefits package on top of their pay,” he said.

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

Twitter: PPHEricRussell

Comments are no longer available on this story