Have you read about the egg spoon culture war? Well, in an eggshell, the saga goes like this.

During a “60 Minutes” episode aired in 2009, Slow Food spirit mother Alice Waters celebrates simple, local ingredients by cooking an egg over an open fire for Leslie Stahl in a hand-forged gadget specially made for the job. Outspoken celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain then calls Waters out as an elitist, because, he asks, what average American family has the luxury of a fireplace in their kitchen?

There is some angst, but the fury subsides. Fast-forward to January 2018, when in a column in New York Magazine, Tamar Adler, a food writer and Waters’ protégé, cops to eating an egg made with a egg spoon (given to her as a wedding gift). Around the same time Waters’ daughter, Fanny Singer, commissions a blacksmith to forge egg spoons in her mother’s name that she sells for $250 on her high-end web site, Permanent Collection.

The Internet explodes with criticism that mirrors Bourdain’s original sentiment, this time noting the steep price as the measure making the spoon untouchable for most. Feminists use their collective voice in this post-Harvey Weinstein era to loudly question why male chefs and food writers aren’t similarly chastised for espousing expensive one-trick pony kitchen gadgets.

I am Switzerland in this conflict, as I would gladly eat anything that either Waters or Adler cooked for me regardless of the method, but I don’t subscribe to single-use kitchen tools as a matter of green cooking course.

I’ve been given things like gravy separators and garlic presses over the years, of course. But as a practical cook I lean on my sharp knives, cast-iron pans, sheet pans, wooden spoons, a microplane grater, stand mixer, mismatched measuring cups and spoons, and melon baller to make my family’s food. I like my tools to do a minimum of three kitchen tasks each. Why then was I avoiding the plug-in multicooker craze? Electric pressure cookers at their core, these appliances have been technologically adapted to also serve as slow cookers, yogurt makers, steamers and stockpots.

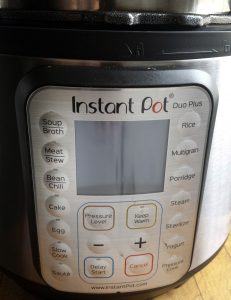

Instant Pot is the most prevalent brand name for these post-modern set-and-forget countertop cookers, which are colloquially called instapots. Instant Pots first hit the market in 2010, and the company releases updates like Apple does for iPhones. Breville, Gourmia, KitchenAid, Ninja, Phillips, Presto, T-fal and VitaClay also make multicookers with prices that range between $80 and $250. The Internet buzz around these things is palpable. There are almost 90 Facebook Instapot community groups, divided by region, diet (vegan, keto, gluten-free, paleo) and sense of humor (Blood Type A, InstantPot Group, Instant Pot-Heads). Amazon sells over 150 cookbooks with “Instant Pot” in the title.

I’ve already, semi-scientifically, determined that a countertop pressure cooker was the most energy-efficient way to produce a pot of beans. So when I borrowed a friend’s fourth-generation Instant Pot last week, I did so with the intention of determining whether it could help me be a greener cook. Would it save me time and personal energy when cooking the last of the winter root vegetables? Would it allow me to buy the cheaper cuts of pastured meat I can readily afford but want to tenderize quickly? Could I really make a perfect pot of rice every time, cut down on kitchen water usage for either dinner prep or washing up, and make my own worry-free yogurt in a drafty old house?

My test run centered on my Easter dinner production. I hard-pressured eggs, steamed beets, made yogurt, glazed salmon, cooked a cheesecake, poached pears, and combined an Instant Pot full of local beans and another full of broth made from the spent smoked ham bones for Easter Monday leftovers.

Every process was indeed quicker than making any of these items on or in my natural gas range. But the time savings was not as big as I’d have guessed. Yes, prep time was less as the beans were not pre-soaked, the vegetables could stay whole, the yogurt temperature did not need to be tended to, and the actual cook times for tender meat and succulent fish were cut by half in most cases and even more than that in others. But you must factor in the time it takes for the pressure to build inside the device (about 30 minutes for high pressure) and the time it takes for the pressure to dissipate once the process was over (another 45 minutes for high pressure). These devices do have a manual release, and some recipes call for a cook to stand back and let the steam shoot out at full force. That is a loud, hot process that resulted in both a bigger time saving on dinner as well as a nice steam-clean of the cabinetry sitting above the cooker.

My borrowed Instant Pot has a sauté function, and should I take the plunge myself, that function would be a requirement. Some instapot recipes I tested suggested removing the cooked items from the pot and transferring the sauce to a pan to boil down on the stove. I revised those recipes to tap into the sauté function and avoid the extra washing up, which involved lifting the stainless steel pot out of the heating element to wash with soap and water. In some cases, the metal pot retained the smells of the stronger ingredients, but steaming a spent lemon half inside the device with 2 cups of water for just a couple of minutes cleared the odor.

The best surprise the Instant Pot delivered, though, was how it produced hard-cooked, farm-fresh eggs that were actually easy to peel! The shells on really fresh hard-boiled eggs tend to stick, making them troublesome to peel and leaving pock-marked eggs. Supermarket eggs are usually older; first, they must travel from the factory farm to the grocery store shelf, then they may sit for a spell before someone buys them. As the eggs age, the shell’s protective coat slowly wears off and the egg absorbs more air. The membrane on the inside of the shell weakens its grip and the egg white shrinks, all of which makes the egg easier to peel. Those same things happen to farm-fresh whole eggs made hard in a pressure cooker in 13 minutes flat (4½ minutes to pressurize, 8 minutes to cook, 30 seconds to let off steam).

While I won’t pick a side in egg spoon culture wars, I will admit it was the way the instapot handled hard-cooked eggs that pulled me over to its side of the argument.

CHRISTINE BURNS RUDALEVIGE is a food writer, recipe developer and tester, and cooking teacher in Brunswick, and the author of “Green Plate Special,” a cookbook from Islandport based on these columns. She can be contacted at cburns1227@gmail.com.

CORRECTION: This story was updated at 11:30 a.m. Monday, April 9, 2018, to correct the price on an egg spoon.

Comments are no longer available on this story