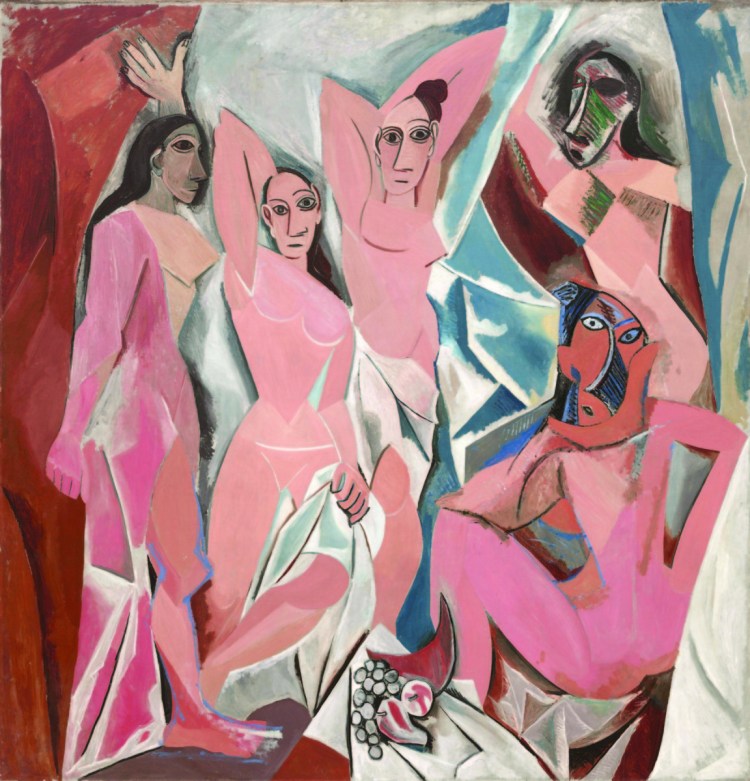

An “exorcism painting.”

That’s how Pablo Picasso described “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” what some experts consider the first example of cubism and all acknowledge as a primary portal to modernism.

Created in 1907, the painting was so revolutionary that it rattled the artist himself. Picasso rolled up the canvas and stashed it away, stung by peers’ scorn and wrung out by the eight months he’d spent conjuring it in his seedy Montmartre studio. Only Georges Braque, with whom Picasso would soon share an uncharacteristically cooperative partnership, quickly gleaned the canvas’ utter originality. It took years for the cognoscenti to reckon with and admire the way this remarkable work shattered and reconstituted artistic paradigms.

“Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” is a group portrait of five prostitutes in a brothel. Its semi-sensical planes are spliced and splintered. The figures’ primitive, angular proportions are wildly distorted, echoing ancient Iberian sculptures Picasso had seen at the Louvre, and the two women on the right have faces reflective of African masks that the artist admired. A platter of fruit in the foreground is stony, a curiously off-putting emblem of what should be inviting.

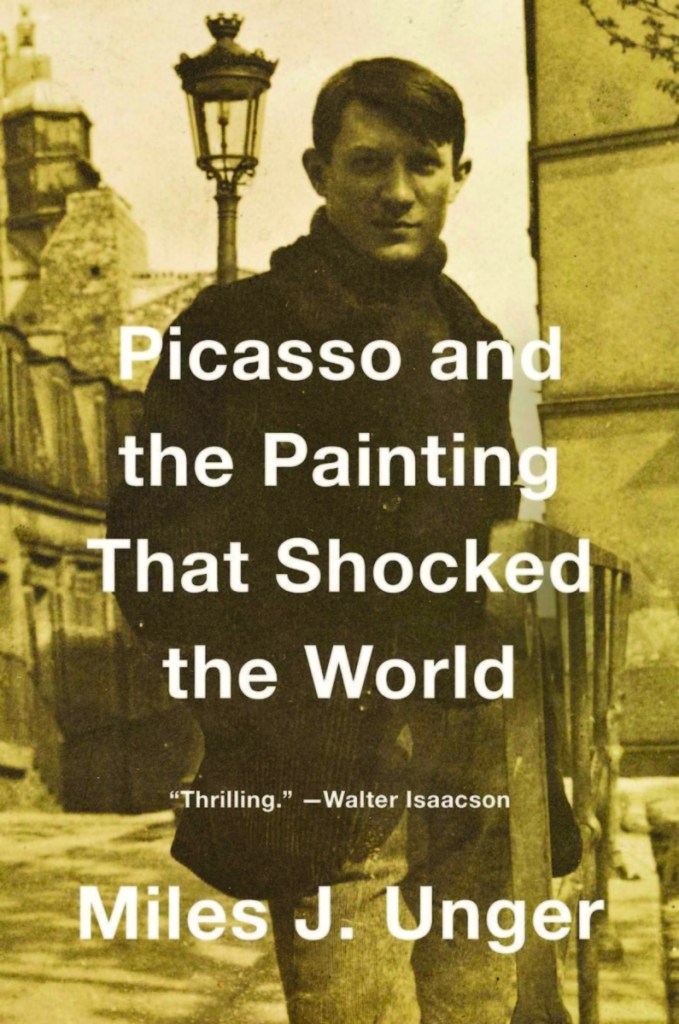

“Les Demoiselles” is “a cathartic painting, a great cry of lust, anger, anguish, and release – a form of black magic in which Picasso summons his demons in order to vanquish them,” writes Miles J. Unger in “Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World.” Unger, a culture writer for the Economist who has also written books on Michelangelo and Winslow Homer, closely chronicles Picasso’s painful but liberating exorcism, the social and aesthetic factors that contributed to it, and the cubism it messily birthed.

If you’re an art lover, this is an engrossing read. Unger draws not just from his own wide knowledge and considered taste but from an imposing array of journals, memoirs, biographies and periodicals. From these he offers a historically and psychologically rich account of the young Picasso and his coteries in Barcelona and Paris.

The author escorts us into the painter’s bare-bones studio, so cold in winter that tea froze in its cup. We accompany the volatile, sparkling-eyed charmer to the slummy muraled cafes and dance halls where artists, writers, journalists and models drank, flirted and quarreled. We stroll the dark streets where muggers lurked in wait for day-trippers eager to sample the hillside Montmartre demimonde on Paris’ periphery. We venture into town to visit the cluttered storefront galleries of sometimes unscrupulous art dealers, and the erudite but combative enclaves of prescient collectors like the Steins.

Picasso was stirred by symbolism, fauvism and the stylistic innovations of, among others, El Greco, Ingres and Cézanne. He was energized by the street-savvy renderings of Toulouse-Lautrec and taken with the winsome savage innocence of Gauguin and, to some degree, Henri Rousseau. He responded also to the literary currents of the time, channeled through André Salmon, Guillaume Apollinaire and other writer friends. But most of all, Picasso wanted to be like no one else. Fiercely competitive, he amplified ugliness to counter the prettiness of his professorial arch-frenemy Henri Matisse. Their quest to be at the sword’s tip of the avant-garde inspired and exhausted them both.

Given his later fame and wealth, it’s easy to forget that Picasso’s first journeys to Paris to become an artist ended with his retreat to Spain, seeking handouts and reassurance from his family even as he ridiculed their parochialism.

But by 1907, Picasso’s Paris buyers had finally come around to the melancholy blue-period paintings redolent of death and mourning after the suicide of his artist and poet friend Carlos Casagemas. Aficionados were also embracing the opium-warmed reveries of Picasso’s rose period. Any other painter, in that situation, would have simply kept churning out those sought-after blues and roses. Finally, a signature style!

Not Picasso.

Though self-centered, calculating, jealous and sometimes cruel, he was also truly visionary – or, more accurately, in an unrelenting quest for whatever vision came next, as long as it was altogether original. With “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” he ruptured the planes of the two-dimensional canvas. In affinity with Cézanne, he asserted the painting as an object in itself, not a mere rendering of objects.

“Les Demoiselles” tore apart and reordered reality, turning a traditional sensual motif into a grotesque, scary grouping of angular naked forms that bust every which way out of their frame, sexually confusing and intimidating us while testing our visual sanity. Unger and others see the work as, among other things, a nightmarish vision of venereal disease, with which Picasso may well have had some experience.

“The women themselves may be singularly unsexy,” Unger writes, “but the rhythmic push and pull to which space is subjected diffuses the erotic charge across the entire surface of the canvas – an instance of what Freud would term polymorphous perversity, i.e., the childish impulse to seek gratification in all sensation.”

“Working mostly at night in the cramped, filthy, ill-lit studio,” he writes, “this man, who thrived on conviviality, was forced to become a solitary pilgrim to a goal he could not see and could barely even imagine. … For weeks on end, these ‘monsters’ were practically Picasso’s only companions as his friends fled and his domestic life spiraled downward.”

Readers enamored of this crucial moment in art history might complement Unger’s detailed telling with the more panoramic and accessible “In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and the Birth of Modernist Art,” by Sue Roe. The two books together – Unger’s in close-up, Roe’s in the broad view – wonderfully capture how Picasso’s personal history, temperament and aesthetic development combined with the revolutionary currents in turn-of-the-century Parisian culture to bring about this unforgettable depiction of five primordial she-devils, a painting that Picasso’s writer friend André Salmon called “the incandescent crater from which emerged the fire of present art.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story