Just months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, launching the United States into World War II, America began an unprecedented civilian effort to gather and recycle materials that would ultimately ensure victory in Europe and the Pacific.

When war production in the United States moved American production “from refrigerators to machine guns,” a serious shortage of raw materials presented a huge problem, one that was left to the American public to solve.

With slogans such as “Salvage for Victory” and “Get in the Scrap,” the citizens of the Midcoast — both male and female, young and old alike — joined the rest of Maine’s citizens in doing their part to bring victory to America.

Public campaigns from coast to coast called for a massive collection of scrap materials for reuse in military production. “Steel, copper, tin, lead, aluminum, iron, and brass” were needed for the “production of planes, tanks, ships, guns, munitions, and military vehicles.”

Rubber was needed to create “tires, rafts, boots, ponchos, gas masks, pontoons, and gaskets.” Nylon silk was needed for the manufacture of ropes, parachutes and gunpowder bags.

Scrap paper was needed for “draft cards, discharge papers, orders, reports, telegrams, correspondence, field ration packaging, and parachute flares.”

Kitchen grease, leftover from the cooking of meats, was needed for lubricants and the production of glycerin for explosives, as “one tablespoon of waste-fat per day would load 1,542 machine-gun bullets per year.”

Milkweed floss was needed from fields and backyards to create life preservers as “a single pound of floss could keep a 150-pound person afloat.”

Donated binoculars, typewriters and even the family dog were necessary in order to win the war. Over “40,000 family [pet] dogs were donated for war-time service.”

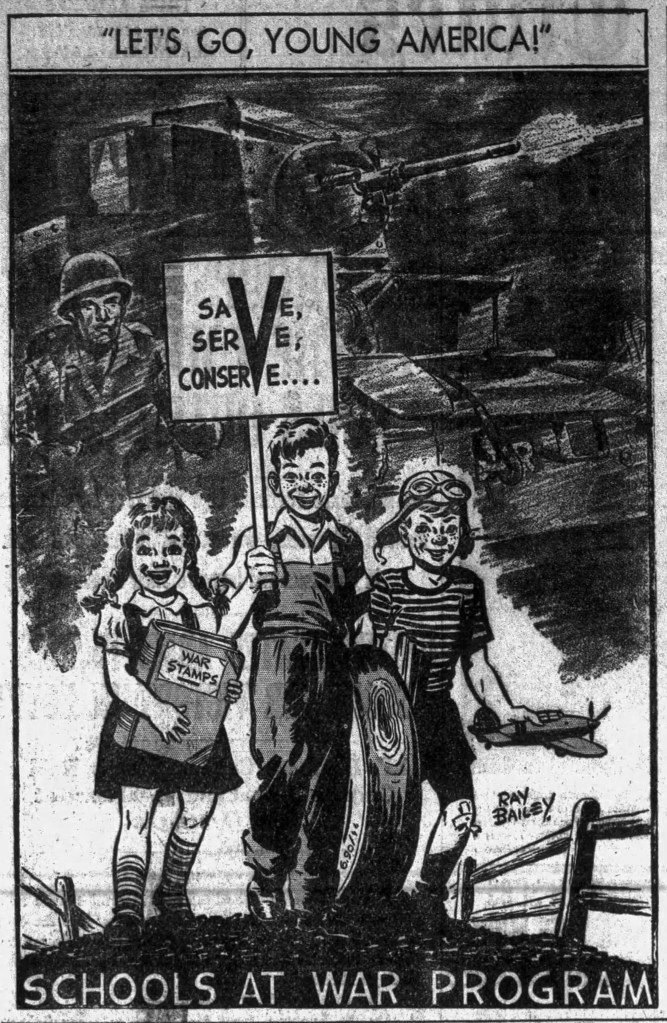

Local campaigns to scrounge scraps were organized by schools, individuals and groups such as the Lions and Rotary Clubs, Veterans of Foreign Wars, American Legion, and the Boy and Girl Scouts.

Many communities surrendered “historic cannons, plaques, monuments, and wrought iron fences from cemeteries” for the war effort.

Families surrendered “hot water bottles, rubber bands, garden hoses, old tires, goulashes, raincoats, and even the kid’s rubber-duckies.”

Bundles of newspapers, old books, magazines, posters, paper labels, phone books and city directories, and note pads were gathered to produce the more than “700,000 military products [that] used paper.”

Many trucks, tractors and family cars were stripped down of their fenders, bumpers, jacks, hub caps and other expendable metals.

Women gave up pots, pans and utensils, all while surrendering their nylon legwear and other intimate silk or rayon apparel. It took “2,300 nylon stockings to make a parachute.”

Children collected old bicycles, metal toys and anything they could find, including foil from gum wrappers and cigarette packs, in order to bolster their contribution to the war.

Every American citizen took part in the “greatest recycling effort in American history,” and the munitions plants, shipyards and defense factories took those recyclables and churned out historic volumes of every kind of wartime necessity.

On Labor Day in 1942, a scrap drive rally was held on the Brunswick Mall with a “rally and band concert.” The drive brought a mass donation of over “25-tons of scrap” for the war effort.

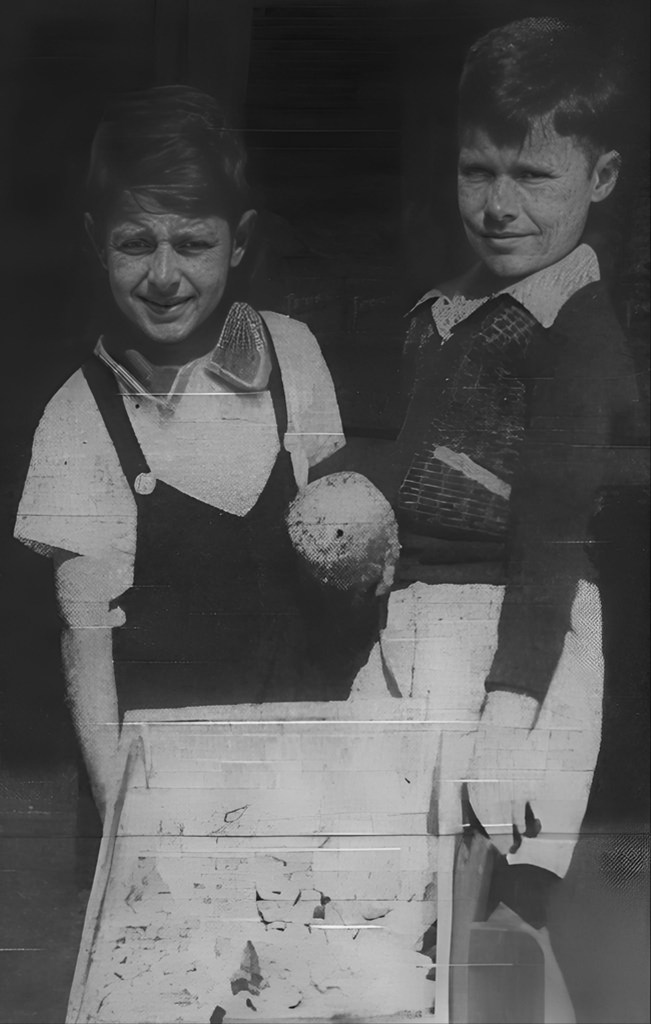

One “gang of Topsham boys” spent an entire afternoon digging out “a tractor mired in the mud behind the Aldrich residence on Elm Street. Allen White, James, Robert and Howard Hall, James Coombs, Leroy Clemmons, and Byron Harrington … transported it to the Brunswick Mall scrap drive.”

Many cast iron street signs and stoop-side handrails suddenly vanished. Even “the old rails” of the Brunswick Trolley “on Maine Street … were to be taken up” for the war need.

By late October 1942, “approximately 100 tons of scrap [were] collected in Brunswick, with 17,025 pounds of scrap collected by students of the Brunswick High School alone.” One month later, “Maine [was] third in the country in deliveries to smelters of scrap steel.”

In March 1943, “Maine was expected to raise 79,000 tons of scrap metals … 1,200 tons of tins cans … 2,112 typewriters … and 759,000 pounds of kitchen fats.”

In January 1944, “children of the Bath elementary schools collected well over 30-tons of waste paper” in just one week.

The national “Salvage for Victory” campaign was an unprecedented success and one in which all Americans could be proud to have participated. Millions of tons of salvage were collected nationally and put to good use in winning the war.

Today, we remember a time when each American worked together, doing the improbable and becoming the greatest generation ever included in our Midcoast Stories from Maine.

Historian Lori-Suzanne Dell has authored five books on Maine history and administers the popular “Stories From Maine” page on Facebook, YouTube and Instagram.

Comments are not available on this story. Read more about why we allow commenting on some stories and not on others.

We believe it's important to offer commenting on certain stories as a benefit to our readers. At its best, our comments sections can be a productive platform for readers to engage with our journalism, offer thoughts on coverage and issues, and drive conversation in a respectful, solutions-based way. It's a form of open discourse that can be useful to our community, public officials, journalists and others.

We do not enable comments on everything — exceptions include most crime stories, and coverage involving personal tragedy or sensitive issues that invite personal attacks instead of thoughtful discussion.

You can read more here about our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is also found on our FAQs.

Show less