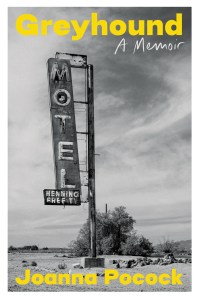

“Greyhound: A Memoir” By Joanna Pocock. Soft Skull. 388 pages. $18.95, paperback (Soft Skull)

The mythic notion that is the Great American Road Trip has been romanticized, and occasionally punctured, by writers since the time before pavement. A smaller, scrappier subgenre has grown up around the cross-country journey by bus. As Joanna Pocock demonstrates in “Greyhound,” her account of traveling from Detroit to the California coast, this mode of transport offers a unique shortcut to the true heart of America – and shows how stressed and deeply unwell that organ is right now.

Pocock, an Irish Canadian writer living in London, first undertook this trip in 2006 as salve for a double grief: the loss of a pregnancy and of her sister. She composed her route to visit sites important to the protagonist of a novel she was writing. Seventeen years later, she retraced her earlier journey, and “Greyhound” is the result. The country on the other side of the grimy bus window has degraded in multiple distressing ways: socially, economically, environmentally.

Inside the vehicle, it’s not much better. The digital technology onto which we have off-loaded social interaction has effectively eradicated the camaraderie of this most populist form of getting from one place to another. Pocock has fewer conversations with fellow riders in 2023 and notices that displays of generosity during the shared experience have dwindled. Her observations on the toll of the “appification” of life are just one part of her critique of the ongoing disassembly of the commons, in its widest sense.

Bus stations, once shelters and communal meeting spaces, are literally shells of their former selves, if not closed entirely. Life has increasingly hardened for those who rely on intercity buses. Pocock witnesses numerous people weeping as they beg to board, lacking the means to buy a ticket, and around the stations she frequently sees “alarming levels of poverty, disenfranchisement, addiction and hopelessness.”

Tellingly, the iconic American Greyhound is not even American anymore. It is owned by Flix, a German corporation that continues to move its operations to a curbside model. Bus stations occupy valuable real estate, and their personnel must be paid. Boarding at a roadside bus stop is economical – for the company. As Pocock discovers in the blazing heat of Phoenix, however, waiting for a connecting bus in a concrete wilderness of heavy traffic is not only inconvenient, it can also be hazardous.

Her attempts to get reliable information about arrival times from an online tracker read like something out of the theater of the absurd. She warily books herself into a Detroit hotel that operates only via email and app (“There are no humans involved”). She researches who owns the hotel, and after reading a bland, jargon-filled mission statement by the company’s CEO online, she thinks: “I was sleeping in a bed built by corporate ideology and zealotry.”

The miseries of the passengers around her and of the ravaged landscape through which the bus speeds (especially in the desert West) have varied causes. But none of them have been improved by the hegemony of extractive technologies that purport to make life easier and more “seamless.” Instead, Pocock sees evidence that “the machine is taking over,” shredding the social fabric and accelerating the depletion of natural resources – not to meet “our” energy needs but those of the technologies to which we have become subservient.

It is a testament to Pocock’s subtlety and skill that “Greyhound” can do so much without flashing neon signs over the various points it makes. Transitioning with deceptively light grace through its many significant subjects, the book flows like scenery past a windshield. It encompasses inner journey, feminist critique, engaging travelogue, examination of literary predecessors (including Alexis de Tocqueville, Jack Kerouac and Simone de Beauvoir) and accounts of environmental depredation, from Las Vegas to a vast solar-thermal farm in California whose main success appears to be killing birds. The book deserves its own slogan: Go Greyhound and Leave the Driving to Her.

Lyrical and clear-eyed at once, Pocock has reinvented the road-trip genre for a new age – an age, she argues, in which we lack the will to fully confront the drastic effects of our political and economic decisions. These consequences include the “ecocidal madness” that continues apace and the many people left behind (“people without cars who cannot easily move from one place to another are a population who do not matter in the U.S.”). Yet given all that, the book is not without a curious sort of hope. The many photos that punctuate its pages – even scenes of blank desolation and tattered urban streetscapes – betray the photographer’s affection for peculiarly American attributes, most notably cussed persistence.

“My fellow Greyhound travellers and I were on a tarmac sea sailing to ports known and unknown, unmoored from and unaware of the deep time that had shuttled us all into our present,” Pocock writes with customary understated elegance. Her ground-level view onto this forgotten America, from her seat in the lowly yet vital public bus, enables us to see exactly what needs to be remembered.

Melissa Holbrook Pierson is a critic and the author of “The Place You Love Is Gone,” among other books.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can update your screen name on the member's center.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your Press Herald account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.