Charlie Eshbach, who helped establish the Portland Sea Dogs as one of minor league baseball’s model franchises, died Tuesday morning following a lengthy illness.

He was 70 and had been hospitalized since May, team officials said.

Eshbach was the Sea Dogs’ first employee and served as team president for 25 years. In 2013, he was named “King of Baseball,” minor league baseball’s highest honor, for his work in building family-friendly entertainment at Hadlock Field. His impact on the community went even deeper as co-founder of the Strike Out Cancer In Kids program that has raised more than $5 million since launching in 1995.

Eshbach was hired by then team owner Dan Burke in October 1992, stepping down as Eastern League president to oversee building a club that would begin play in 1994 as a Double-A affiliate of the expansion Florida Marlins.

Burke and Eshbach both were lifelong Red Sox fans, and the Sea Dogs switched affiliations from Florida to Boston following the 2002 season. The Red Sox connection led Eshbach to tweak Hadlock Field to more closely resemble Fenway Park, with changes as obvious as a 37-foot left-field wall dubbed “The Maine Monster” and as subtle as the Morse code initials on either side of the scoreboard honoring Burke (DBB) and his wife, Bunny (HSB).

“He and my dad made this perfect match,” said Bill Burke, who along with his sister Sally McNamara assumed ownership of the club following their father’s death in 2011. “Running a minor league team is a lot of work and he made it look easy.”

Burke and McNamara called Eshbach “the heart and brains” behind the Sea Dogs, named in 1999 by “Baseball America” magazine as the best operation in minor league baseball. Eshbach also served as Portland’s general manager through the 2010 season, and remained with the club as a senior adviser after stepping down as team president in September 2018.

MINOR LEAGUE EXEC AT 22

He grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts, earned a degree from the University of Connecticut and became general manager of the Bristol (Connecticut) Red Sox at age 22. He was 29 when elected president of the Eastern League and served in that capacity for 11 years, until Dan Burke convinced him to join the expansion franchise in Portland.

“I just felt Charlie was the perfect person for a community like Portland,” Dan Burke told the Press Herald in 1994. “Charlie’s a marathoner, not a dash man.”

It was in Bristol that Eshbach met Guy Gilchrist, an artist and illustrator who drew a comic strip based on Jim Henson’s Muppets and was a regular at Muzzy Field.

“We were both big Red Sox fans,” Gilchrist, 65, said Tuesday from his home in Nashville, Tennessee. “Charlie really learned the whole business from the ground up. You were not only the general manager, but you were serving hot dogs.”

At the time Eshbach moved to Maine, there were only two notable mascots in minor league baseball, Gilchrist said, the Durham Bull in North Carolina and the Toledo Mud Hen in Ohio. Dan Burke was against the idea of a mascot, his son said, but Eshbach prevailed, and sent Gilchrist some of the suggested team names, including Puffins and Wharf Rats along with Sea Dogs.

While on the phone with Eshbach, Gilchrist sketched a young seal wearing a ball cap with a P and chomping on a bat. The Sea Dogs logo was born, and mascot Slugger became the lovable face of the franchise.

The team continues to rank among the top 25 franchises in minor league baseball in annual merchandising sales.

“He was more business-oriented with his background and I was more of an arts background, but we both loved all the same stuff,” Gilchrist said. “Charlie had an imagination, and he had the business acumen to put imagination into motion.”

‘HE INSTILLED IN US A PRIDE’

Promotions are a staple of minor-league life, but Eshbach nurtured a family-friendly atmosphere and never allowed between-innings entertainment to encroach upon the game itself. In 1997 he pioneered the Field of Dreams-inspired entrance of flannel-uniformed players and coaches through a makeshift cornfield in center field.

The Sea Dogs never embraced promotions such as dizzy bat races where fans are made to look foolish.

The idea is “to treat everyone with respect and have a good time,” said Jim Heffley, the Sea Dogs business manager who joined the club as a 23-year-old in 1994. “I’ve never met anyone so dedicated to the integrity of the game. He always reminded us that they’ve got a job to do and we can’t get in their way.”

Heffley is among the longtime Sea Dogs employees who spoke of Eshbach’s integrity and loyalty. He regularly stood at the front gate before games, welcoming fans and listening to any concerns. He was never Mr. Eshbach, always Charlie.

“He instilled in us a pride,” Heffley said. “He mentored and guided us on how to do things correctly. We learned early on: Don’t do anything that will embarrass the club.”

Susan Doliner has been with Maine Medical Center’s philanthropy department since 1990. She and Eshbach helped develop the wildly successful Strike Out Cancer In Kids program.

She said Eshbach and the Burke family wanted to create more than a local ball club.

“They wanted a link to the community and to give back,” she said.

A golf tournament called the Slugger Open also raises money for the Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital.

“Charlie made sure the players would come up and meet the children,” Doliner said of the patients in the pediatric unit, which overlooks the ballpark. “The ballplayers knew what it was like to have a child look up to them. And often a player would come up on his own.”

Doliner said she would often travel outside of Maine to tout the success of the Strike Out Cancer partnership. She described Eshbach as quiet and wise but with a great sense of humor.

“I also got to be around him when he was around his professional colleagues and boy, did they respect him,” she said. “He wasn’t just respected around Portland but around the country.”

‘CHARLIE WAS THE GOLD STANDARD’

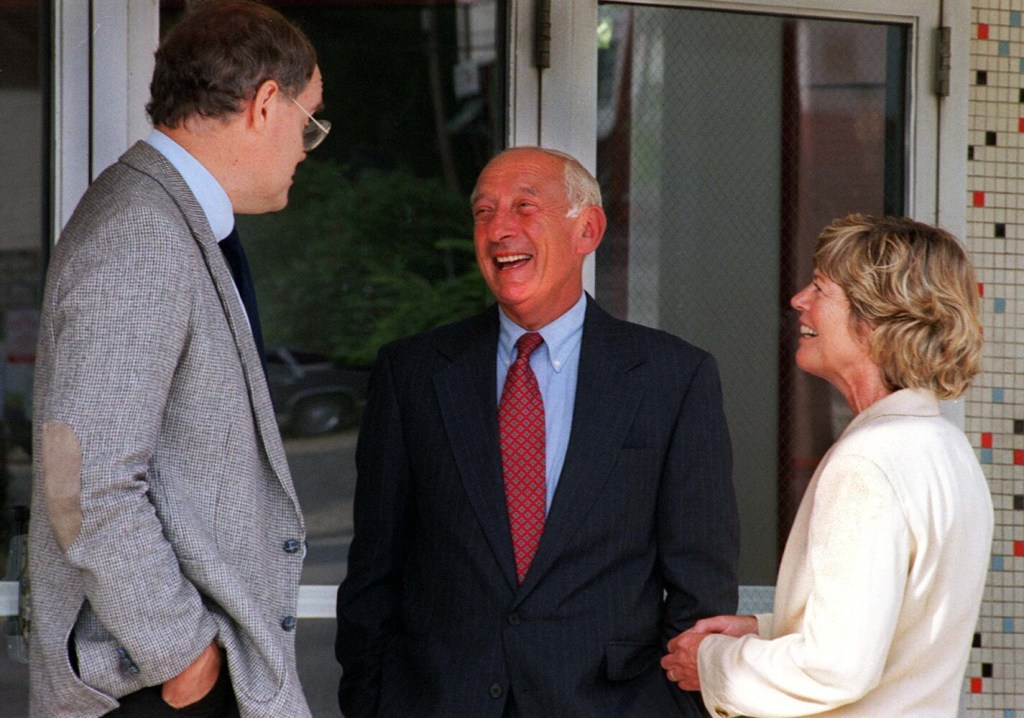

Jon Jennings was exploring where in New England to put an expansion minor league basketball team in 2007. Intrigued by the success of the Sea Dogs, he approached Eshbach, who pitched the idea of Portland.

The Red Claws, now called the Maine Celtics, played their first game in November 2009. Jennings was the team’s president and general manager for the first three seasons before becoming Portland’s city manager, a position he currently holds in Clearwater, Florida.

“Charlie was the gold standard that I based all of the decisions around when we were creating the Red Claws,” Jennings said. “I met with him on several occasions to get his thoughts. He was integral to the success that we actually had with the Red Claws in the beginning.”

Eshbach stressed that a minor league team had to be a part of the community, beyond the game-day event, Jennings said.

“That was frankly the hallmark of what Charlie taught me,” Jennings said. “We wanted to be a vital part of the community and wanted to make a difference, and many of the things we did, from the promotions to the fundraising events that we did as a team, grew out of those initial conversations with Charlie.”

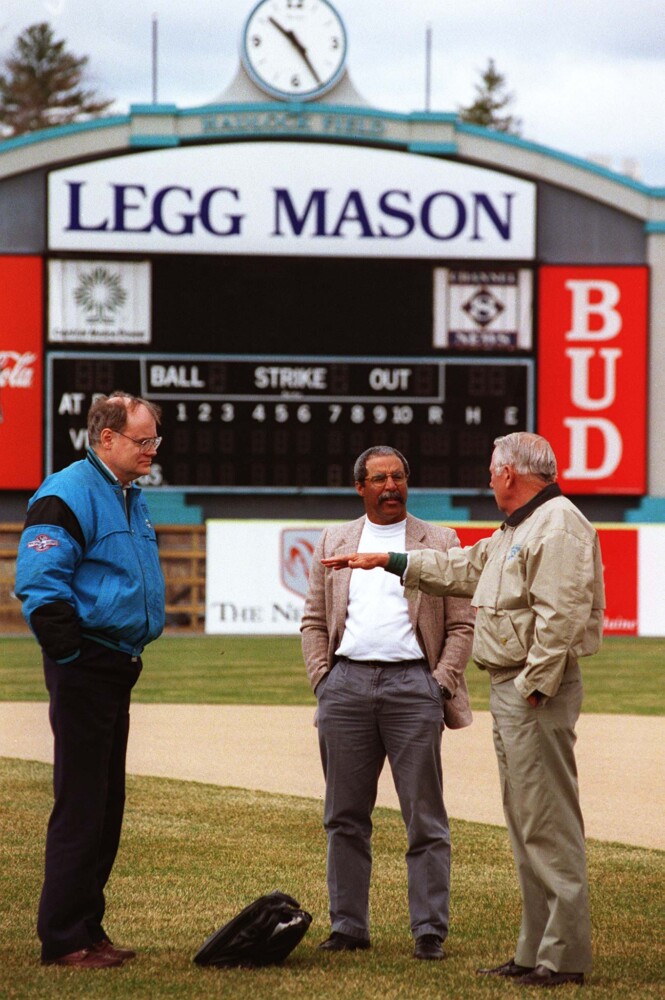

Carlos Tosca, manager of the Sea Dogs in their first three seasons, choked up upon hearing the news of Eshbach’s death Tuesday afternoon.

“His character and his honesty – I don’t want to say they were rare in the minor leagues – but he was certainly a cut above,” he said by phone from Florida. “He had such an easygoing way, but at the same time, you knew there was fire and intensity in there.”

Tosca was silent for a moment.

“He did things right,” he said of Eshbach. “I loved the man. He took very good care of me and he always made sure the players were taken care of.”

Eshbach and the Sea Dogs earned several honors during his tenure. In 2000, Minor League Baseball awarded the Sea Dogs with the John H. Johnson President’s Trophy, presented to the baseball franchise for its stability and contributions to the league, its community and the baseball industry overall. Eshbach was named the Eastern League Executive of the Year in 1978 (while with Bristol), 1994 and 2002.

Tosca said Eshbach’s two decades of baseball experience before the Sea Dogs meant that “nothing really ruffled his feathers, nothing ever caught him by surprise,” the former manager said. “They don’t make ’em like that anymore.”

Staff Writer Steve Craig contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story