NEW YORK — We go to movies not just to escape, but to discover. We might identify with the cowboy or the runaway bride or the kid who befriends a creature from another planet.

To see yourself on screen has long been another way of knowing you exist.

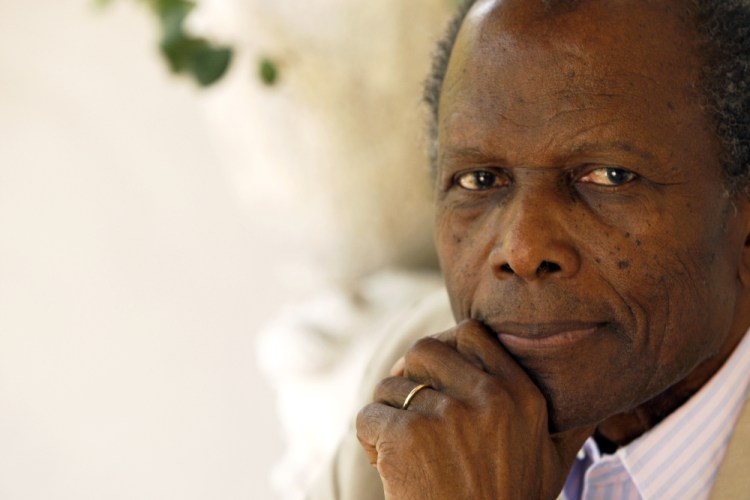

Sidney Poitier, who died Thursday at 94, was the rare performer who really did change lives, who embodied possibilities once absent from the movies. His impact was as profound as Method acting or digital technology, his story inseparable from the story of the country he emigrated to as a teenager.

“What emerges on the screen reminds people of something in themselves, because I’m so many different things,” he wrote in his memoir “The Measure of a Man,” published in 2000. “I’m a network of primal feelings, instinctive emotions that have been wrestled with so long they’re automatic.”

Poitier made Hollywood history by breaking from the stereotypes of bug-eyed entertainers, and American history by appearing in films during the 1950s and 1960s that paralleled the growth of the civil rights movement. As segregation laws were challenged and fell, Poitier was the performer to whom a cautious Hollywood turned for stories of progress, a bridge to the growing candor and variety of Black filmmaking today.

He was the escaped Black convict who befriends a racist white prisoner (Tony Curtis) in “The Defiant Ones.” He was the courtly office worker who falls in love with a blind white girl in “A Patch of Blue.” He was the handyman in “Lilies of the Field” who builds a church for a group of nuns. In one of the great roles of stage or screen, he was the ambitious young man whose dreams clashed with those of other family members in Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun.”

Poitier not only upended the kinds of movies Hollywood made, but how they were filmed. For decades, Black and white actors had been shot with similar lighting, leading to an unnatural glare in the faces of Black performers. On the 1967 production “In the Heat of the Night,” cinematographer Haskell Wexler adjusted the lighting for Poitier so the actor’s features were as clear as those of white cast members.

The long-running debate over Hollywood diversity often turns to Poitier. With his handsome, flawless face, intense stare and disciplined style, Poitier was for years not just the most popular Black movie star, but the only one; his unique appeal brought him burdens familiar to Jackie Robinson and others who broke color lines. He faced bigotry from whites and accusations of compromise from the Black community. Poitier was held, and held himself, to standards well above his white peers. He refused to play cowards or cads and took on characters, especially in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” of almost divine goodness. He developed an even, but resolved and occasionally humorous persona crystallized in his most famous line — “They call me Mr. Tibbs!” — from “In the Heat of the Night.”

“All those who see unworthiness when they look at me and are given thereby to denying me value — to you I say, ‘I’m not talking about being as good as you. I hereby declare myself better than you,’” he wrote in “The Measure of a Man.”

Sidney Poitier signs autographs before the opening of the International Film Festival at the West Berlin congress hall on June 26, 1964. Associated Press/Edwin Reichert

In 1964, he became the first Black performer to win the best actor Oscar, for “Lilies of the Field.” He peaked in 1967 with three of the year’s most notable movies: “To Sir, With Love,” in which he starred as a school teacher who wins over his unruly students at a London secondary school; “In the Heat of the Night,” as the determined police detective Virgil Tibbs; and in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” as the prominent doctor who wishes to marry a young white woman he only recently met, her parents played by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in their final film together.

In 2009 President Barack Obama, whose own steady bearing was sometimes compared to Poitier’s, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying that the actor “not only entertained but enlightened … revealing the power of the silver screen to bring us closer together.”

Poitier was not as engaged politically as his friend and contemporary Harry Belafonte, leading to occasional conflicts between them. But he was active in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and other civil rights events and even helped deliver tens of thousands of dollars to civil rights volunteers in Mississippi in 1964, around the same time that three workers had been murdered. He also risked his career. He refused to sign loyalty oaths during the 1950s, when Hollywood was blacklisting suspected Communists, and turned down roles he found offensive.

“Almost all the job opportunities were reflective of the stereotypical perception of Blacks that had infected the whole consciousness of the country,” he later told The Associated Press. “I came with an inability to do those things. It just wasn’t in me. I had chosen to use my work as a reflection of my values.”

Poitier’s films were usually about personal triumphs rather than broad political themes, but the classic Poitier role, from “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” to “In the Heat of the Night,” seemed to mirror the drama the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. played out in real life: An eloquent and accomplished Black man — Poitier became synonymous with the word “dignified”— who confronts the whites opposed to him.

But even in his prime, his films were chastised as sentimental and out of touch. He was called an Uncle Tom and a “million-dollar shoeshine boy.” In 1967, The New York Times published Black playwright Clifford Mason’s essay “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” Mason dismissed Poitier’s films as “a schizophrenic flight from historical fact” and the actor as a pawn for the “white man’s sense of what’s wrong with the world.”

Coretta Scott King, Dr. Ralph Abernathy, left, and Sidney Poitier appear for a viewing of a film on the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in New York on Oct. 22, 1969. Associated Press/Marty Lederhandler

James Baldwin, in his classic essay on movies “The Devil Finds Work,” helped define the affinity and disillusion that Poitier inspired. He remembered watching “The Defiant Ones” at a Harlem theater and how the audience responded to the train ride at the end, when Poitier’s character decided to imperil his own freedom out of loyalty to Curtis’ character.

“The Harlem audience was outraged, and yelled, ‘Get back on the train, you fool!” Baldwin wrote. “And yet, even at that, recognized in Sidney’s face, at the very end, as he sings ‘Sewing Machine,’ something noble, true, and terrible, something out of which we come.”

In his memoir, Poitier wrote that he didn’t have a responsibility to be “angry and defiant,” even if he often felt those emotions. He noted that such historical figures as King and Nelson Mandela could never have been so forgiving had they not first “gone through much, much anger and much, much resentment and much, much anguish.”

“When these come along, their anger, their rage, their resentment, their frustration — these feelings ultimately mature by will of their own discipline into a positive energy that can be used to fuel their positive, healthy excursions in life,” he wrote.

His screen career faded in the late 1960s as political movements, Black and white, became more radical and movies more explicit. He would tell Oprah Winfrey in 2000 that his response was to go the Bahamas, fish and think. He acted less often, gave fewer interviews and began directing, his credits including the Richard Pryor-Gene Wilder farce “Stir Crazy,” “Buck and the Preacher” (co-starring Poitier and Belafonte) and the comedies “Uptown Saturday Night” and “Let’s Do It Again,” both featuring Bill Cosby.

He continued to work in the 1980s and ’90s. He appeared in the feature films “Sneakers” and “The Jackal” and several television movies, receiving an Emmy and Golden Globe nomination as future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in “Separate But Equal” and an Emmy nomination for his portrayal of Mandela in “Mandela and De Klerk.” Theatergoers were reminded of the actor through an acclaimed play that featured him in name only: John Guare’s “Six Degrees of Separation,” about a con artist claiming to be Poitier’s son. A Broadway adaptation of “The Measure of a Man” is in the works.

President Barack Obama presents the 2009 Presidential Medal of Freedom to Sidney Poitier in 2009. Associated Press/J. Scott Applewhite

In recent years, a new generation learned of him through Winfrey, who chose “The Measure of a Man” for her book club, and through the praise of such Black stars as Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Danny Glover. Poitier’s eminence was never more movingly dramatized than at the Academy Awards ceremony in 2002 when he received an honorary Oscar, preceding Washington’s best actor win for “Training Day,” the first time a Black person had won in that category since Poitier nearly 40 years earlier.

“I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney,” Washington said as he accepted his award. “I’ll always be following in your footsteps.”

Poitier’s life ended in adulation, but began in hardship, and nearly ended days after his birth. He was born prematurely in Miami, where his parents had gone to deliver tomatoes from their farm on tiny Cat Island in the Bahamas. He spent his early years on the remote island, which had no paved roads or electricity, but was so free from racial hierarchy that only when he left did he think about the color of his skin.

“Walking on the beach, or sitting on rocks, my eyes on the horizon, aroused curiosity, stirring joy,” he wrote in his 2008 book “Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter” about his time on Cat Island.

By his late teens, he had moved to Harlem, but was so overwhelmed by his first winter there that he enlisted in the Army, cheating on his age and swearing he was 18 when he had yet to turn 17. Assigned to a mental hospital on Long Island, Poitier was appalled at how cruelly the doctors and nurses treated the soldier patients and acknowledged that he got out of the Army by pretending he was insane.

Back in Harlem in the mid-1940s, he was looking in the Amsterdam News for a dishwasher job when he noticed an ad seeking actors at the American Negro Theater. He went there and was handed a script and told to go on the stage and read from it. Poitier had never seen a play and stumbled through his lines in a thick Caribbean accent. The director sent him off.

“As I walked to the bus, what humiliated me was the suggestion that all he could see in me was a dishwasher. If I submitted to him, I would be aiding him in making that perception a prophetic one,” Poitier later told the AP.

“I got so pissed, I said, ‘I’m going to become an actor — whatever that is. I don’t want to be an actor, but I’ve got to become one to go back there and show him that I could be more than a dishwasher.’ That became my goal.”

Poitier’s now-famous cadence and diction came in part through reading and studying the voices he heard on the radio. He found an early job in a student production of “Days Of Our Youth,” as the understudy to another determined young performer: Belafonte. When Belafonte didn’t show up one night, Poitier stepped in and caught the attention of a Broadway director who happened to be in attendance. He was soon in a cross-country touring group — often staying in segregated hotels — and by 1950 had his first notable film role: He played a doctor in an all-white hospital in Joseph Mackiewicz drama “No Way Out.”

Other early films included “Cry, the Beloved Country” and “Blackboard Jungle,” featuring Poitier as a tough high school student, the kind of character he might have had to face down when he starred in “To Sir, With Love.” By the late 1950s, he was one of the industry’s leading performers — of any race. In “The Defiant Ones,” co-star Tony Curtis helped Poitier make history by insisting that his name appear above the title of the movie, as a star, rare status for a Black performer at the time.

By the time he received his Oscar for “Lilies of the Field,” his career and the country were well aligned. Congress was months away from passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, banning discrimination on the basis of race, and a victory for Poitier was so desired in Hollywood that even one of his Oscar competitors, Paul Newman, was rooting for him.

When presenter Anne Bancroft announced his victory, the audience cheered for so long that Poitier was able to re-remember the speech he briefly forgot. “It has been a long journey to this moment,” he declared.

Poitier never pretended that his Oscar was “a magic wand” for Black performers, as he observed after his victory, and he shared his critics’ frustration with some of the roles he took on. But he also believed himself fortunate and encouraged those who followed him.

Accepting a life achievement award from the American Film Institute in 1992, he spoke to a new generation. “To the young African American filmmakers who have arrived on the playing field, I am filled with pride you are here. I am sure, like me, you have discovered it was never impossible, it was just harder.

“Welcome, young Blacks. Those of us who go before you glance back with satisfaction and leave you with a simple trust: Be true to yourselves and be useful to the journey.”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.