There is a moment during the documentary “Truth Tellers” when the artist and activist Robert Shetterly is nearly moved to tears as he talks about his ongoing portrait series, “Americans Who Tell the Truth.”

Shetterly, from Brooksville, seems to be caught off guard discussing the painting series that has consumed him since the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. Anguished about the wartime action and enraged at the media for not telling the truth, he began painting portraits of heroes who stood up for the ideals of the country, often at their own peril, in pursuit of racial, social and climate justice. With each portrait, he carved a defining quotation from the subject into the surface of the paint. Surrounding himself with people he admired while contemplating their inspiring words helped him cope with his rage.

He hasn’t stopped painting. First there were 10, then 20, then 50 portraits. Now there are 260 and counting.

“It never loses its poignancy to me to find another person to paint who’s living with that kind of fierce urgency of the rightness of kindness, courage, compassion, decency, dignity – you know, people living for those values, it’s almost too hard to talk about at times,” he says in the movie.

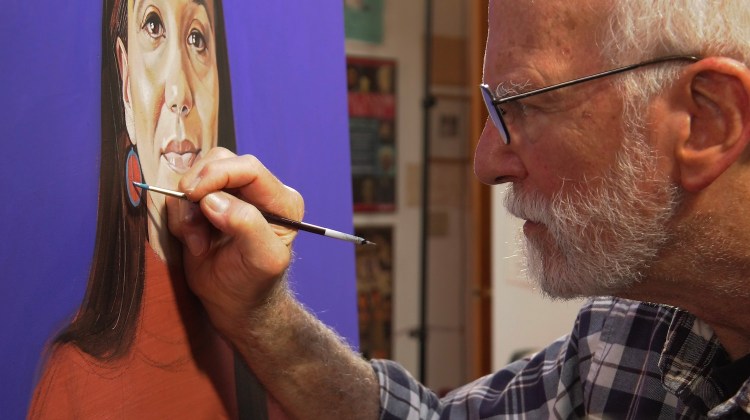

“Truth Tellers,” by Maine filmmaker Richard Kane, explores the trajectory of Shetterly’s series, from his first portrait of poet Walt Whitman to some of his more recent, including Penobscot activist Maulian Dana, whose portrait from 2019 is on the easel as the movie opens. In between are activists, artists and others who have worked to hold the country to account to its founding principles – playwrights Eve Ensler and Langston Hughes, activist Winona LaDuke, artist and educator Natasha Mayers, and policymaker Frances Perkins, all painted with acrylic on 30-by-36-inch wood panels.

A longtime friend of the artist and the energy behind the “Maine Masters” film series about Maine artists, Kane began filming in 2003, when Shetterly started painting the portraits, and began seriously working on the documentary in 2005. In the years since, Kane has filmed Shetterly in the studio painting, in his garden harvesting potatoes, at protests and rallies, and talking with students and others about his work. Kane interviewed many of the subjects of Shetterly’s paintings and was there when some saw their portrait for the first time, so “Truth Tellers” is as much about the subjects of Shetterly’s portraits as the painter.

Kane returned to the film in earnest in 2018, because the moment demanded it. “The politics of our day were so divided,” he said. “There were so many important issues to dig into.”

Race is at the center of many of them. At its core, “Truth Tellers” is about people who have the courage to stand up for the ideals and values of the country, even as the leaders of the country are too hypocritical to do so themselves. “I am fully conscious of the betrayal of the ideals of the country, and it’s the people of color who have embraced those ideals and insisted that they become real for them, and in doing so they are the people who have kept those ideals alive,” Shetterly says in the movie, settling on its theme early on.

“Truth Tellers” captures many moments when Robert Shetterly talks to students, often young children of color, about the activists he’s painted. Here he holds a portrait of Samantha Smith, the Manchester girl who became a peace ambassador after writing a letter to the leader of the Soviet Union, Yuri Andropov, in 1982. Photo courtesy of Kane-Lewis Productions

“Truth Tellers” premiered in September at Camden International Film Festival and will have several screenings across Maine in January, including at 1 p.m. Jan. 9 at the Strand Theatre in Rockland; 7 p.m. Jan. 13 and 2 p.m. Jan. 14 at Lincoln Theater in Damariscotta; and 10 a.m. Jan. 15-16 at Railroad Square Cinema in Waterville. Shetterly and Kane will discuss the film at the screenings Jan. 13 in Damariscotta and Jan. 15 in Waterville.

The release of the movie coincides with the publication of Shetterly’s new book, “Portraits of Racial Justice: Americans Who Tell the Truth,” published by New Village Press. It’s a collection of portraits of people who act with moral courage in pursuit of social justice and includes paintings of Rosa Parks, James Baldwin and Muhammad Ali, and contemporary heroes Zyahna Bryant, who as a 15-year-old petitioned the City Council in Charlottesville, Virginia, to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee, an action that resulted in the removal of the statue in 2021; and the Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr., a civil rights and climate activist who uses hip-hop to engage people in the fight for justice. There are many more, along with a collection of essays.

Robert Shetterly’s “Portraits of Racial Justice: Americans Who Tell the Truth.” Courtesy of New Village Press

The book is the first in a series, Shetterly said in a Zoom call from Brooksville. In 2022, New Village Press will publish a book with his portraits about people fighting for climate justice. “We wanted to begin with the intersection of the two most pressing issues today, which is the continuation of systematic racism and its relationship to climate change, and how they are related to each other,” he said.

Other books might focus on money and power, the media or education. With 260 portraits across a swath of U.S. citizenry, the series can be grouped in many configurations to fit different themes – for books or exhibitions. There is also talk of a miniseries for TV, and Kane is editing a 15-minute version of the film for use in schools. But for all their applications, the portraits at their core are art objects, and “Americans Who Tell the Truth” remains an art project that began with paint on panel as a plea for sanity during a time of war.

The circumstances have changed, but the pleas remain.

A recent subject of Shetterly’s focus is the progressive thinker and policymaker Henry A. Wallace, who was secretary of agriculture for eight years under Franklin D. Roosevelt and vice president until 1944, but then lost favor with the Democratic establishment. “Wallace believed in peacemaking, was anti both military and economic imperialism, wanted to end racism and Jim Crow, was in favor of equal rights for women, national health care, opposed to nuclear weapons, opposed to the Cold War,” Shetterly noted. “If he had become president when FDR died, this country and the world would be a different place.”

Also on the easel is 16-year-old Jaysa Mellers, a young woman of color from Bridgeport, Connecticut, who at age 10 became the face of the movement to shut down a local coal-fired power plant. “Just the beginning of her activist career,” Shetterly said admiringly. “Next I hope to paint someone specifically about gun violence and the proliferation of weapons.”

Shetterly paints to capture the essence and character of his subjects, because he admires them and is inspired by them. As he sits eye-to-eye with their emerging image at the easel, he imagines his subjects watching him as he creates them, imploring him to do his best work. He treats those exhortations seriously. “I take a lot of time to show my appreciation for the people I am painting to paint as good a portrait as I can,” he said.

The project has many overtones. It is about history. It is about politics. It is about education. “But I do not think any of this would be viable without attention paid to the art itself. I have often thought, if I had drawn cartoons about these folks, we would not be having these conversations,” he said. “If the art aspires to be real art, it opens up a space for a dialogue that otherwise would not be there. They are not placards. They are not things we use at a march. They want to be real paintings.”

Shetterly travels across the country to meet with the contemporary subjects he paints, and to talk about the people he has painted who have died. In that capacity, he has become a storyteller. In the movie, Kane captures many moments when Shetterly talks to students, often young children of color, about abolitionist and feminist Sojourner Truth and civil rights activists Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis.

A curious thing happens: He gets invited to a lot of places to tell the stories of the people he paints. Carrying their stories is an enormous responsibility, he said. He has told some of these stories hundreds of times, and he never gets bored and often still becomes overwhelmed by emotion. The courage of these people is astounding, he said. “It gets better with time. I love telling these stories, and I love seeing people react to these stories.”

Such is the role of an artist.

In the movie, Kane includes a scene where Shetterly’s portraits of Lewis, Hamer and abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass are displayed at Monticello, the home of founding father and slave owner Thomas Jefferson. The exhibition in Jefferson’s home gave Shetterly the opportunity to talk about the ideals of the country and what it means to suffer for them. “These are the people who should be there,” Shetterly says of Lewis, Hamer and Douglass, “because these are the people who are fighting the real American revolution, which is to fight and stand up for our real ideals. To see them there at Monticello is very exciting for me and I hope for other people.”

Shetterly wonders how U.S. history would be different had Jefferson given up his slaves. Jefferson and other founding fathers who wrote and influenced the Constitution should have had the self-awareness to pause long enough to reconcile the hypocrisy of their document, he says. They should have recognized that “we’ve got something wrong here. We said equality and justice and freedom and we only gave it to rich white men.”

If Jefferson, George Washington and James Madison instead had given up their slaves and actually granted equality, justice and freedom to all instead of simply talking about it as an abstract ideal to be achieved by others in the future, many of today’s divisive issues would have been resolved long ago, he said. “Think how different the picture of this country would appear if they had that courage,” Shetterly says in the movie.

Courage is the core of “Truth Tellers.”

“We’re never going to be the country we want to be unless we tell the truth about what we have done,” Shetterly says. “And this does not mean you teach children to hate the United States. Quite the opposite. You teach children to love the ideals of the United States so much that they won’t allow themselves to go on perpetrating the crimes the country has been committing in defiance of those ideals. We have to be teaching the truth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story