There’s a helluva lot of testosterone swirling around the planet nowadays. Women, for the most part, aren’t the militaristic impulse behind armed conflicts across the globe or the bomb-carrying drones of Mexican drug cartels (one of the weakest of them parades itself, with no apparent irony, as the Viagras).

Research polls tell us aggression against BIPOC and Asian American and Pacific Island people is up. The Human Rights Campaign recorded 2021 as “the deadliest year on record for transgender and non-binary people.” And let us not forget the egoic space “exploration” (read: joyrides) sponsored by self-indulgent rich white men like Richard Branson, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos as millions starve.

Want a break? Do you long to tap into another powerful energy that offers a less reactive, priapic response to our current reality? Then spend an hour at Speedwell Gallery, where an exhibit curated by artist Annika Earley, “Tenera” (through Dec. 30), welcomes you back into the succor and softness of the womb.

“Tenera” means “tenderness” in Esperanto, a language idealistically invented in the 19th century that sought to create a more humanistically inclusive form of communication. There is no doubt that Earley’s Speedwell show taps into a fundamental truth about humankind that repudiates our current divisiveness by reaffirming our common desire for unity, connection and mother (whether biological or Mother Nature).

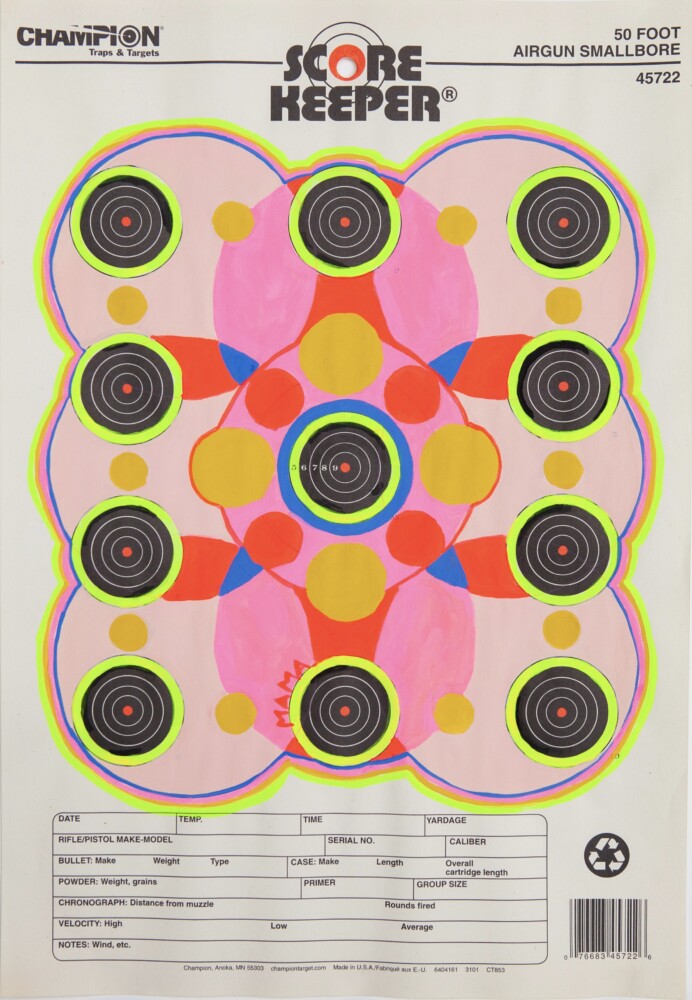

One need only look at the work of Crystalle LaCouture to feel the disjunction between men from Mars and women from Venus. LaCouture titled this series “Mama Drawings” because they arose from the separation imposed by COVID, during which her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Unable to be with her, LaCouture began creating these works on a stack of “Score Keeper” shooting targets she found.

On a personal level, these were love letters to her mother and apt metaphors for a disease that had the woman who gave LaCouture life in its sights. The artist literally disarmed this notion by creating gouache drawings on the “Score Keepers” that obliterated or altered the targets with joyfully bright colors and new compositions, transforming or erasing their normal function as tallies of a shooter’s potentially deadly prowess.

The word “MAMA” is also incorporated into each drawing, powerfully confronting the viewer with the prospect of killing one’s own mother and, by extension, the loving life-giving force of the universe. Diagrams like #30 push the metaphor with flesh-colored shapes that recall breasts (the targets becomes nipples) or interlocking circles that speak of connection and the interdependency of earthly life.

I couldn’t help remembering the tenderly revolutionary act of 1960s flower children inserting daisies into the barrels of the guns they faced down, which were held by riot police intent on quashing what the government perceived as their dangerously passivist demonstrations. Kindness and love, traits traditionally considered the purview of women, were – and continue to be – a threat to a male-dominated status quo that refuses to relinquish its power.

Leeah Joo, “Pojagi Throne Seki,” oil on canvas, 48” x 48”, 2017. Image courtesy of Speedwell Projects

Another poignant evocation of familial female nurturing is the ravishing oil paintings of Korean American artist Leeah Joo. All depict “pojagi,” traditional wrapping cloth made from remnants of clothes and bedding. Joo’s grandmother used these fabrics to cover food she’d prepared, protecting it until it was ready for serving.

You don’t need this context to understand these as thoughtfully wrapped gifts meant for the viewer. The tenderness and kindness inherent in the act of giving are so palpable they might just melt your heart. And because the fabrics are mostly silks, beautifully rendered in their sumptuousness by Joo, they also transmit a preciousness that enhances their emotional impact.

Sharon Chandler Correnty’s fiber works mine the continuity of connection that descends through generations of ancestral roots originating in both Africa and England. “Wedding Ring Dress,” for instance, is a garment conjured from a quilt made by one of her female forebears. The traditional wedding ring pattern of the quilt summons all sorts of associations: the sanctity of marriage, unity, interconnectedness, family, domesticity.

All these institutions can be, and continue to be, weaponized by political opportunists. But what comes across in this garment – because of its personal history and the respect for legacy in its intention – is the incontrovertible truth of human bonds that transcend time and space. It exudes an authenticity free of myth-building or political agendas.

Sharon Chandler Correnty, “Matrilineal Garden,” felted wool, 35” x 62”, 2020. Image courtesy of Speedwell Projects

Correnty’s most materially gorgeous work is “Matrilineal Garden,” a felted wool wall hanging ripe with intimations of fertility, growth, life and abundance. Correnty, an art educator who prefers the term “maker” to “fine artist,” may not have intended this sort of multi-layered transmission. Yet as objects, they almost can’t help telegraphing them.

More provocative, yet ultimately endearing, are Cindy Rizza’s oil paintings of electrically illuminated decorative objects (a little girl holding a Teddy bear in “Beacon II” and a pair of birds on a nest in “Incubator”). The antecedents of these potentially mawkish items are cute Hummel porcelains and doe-eyed Precious Moments figurines.

Yet Rizza’s renditions somehow feel self-aware in a way that sidesteps their saccharine sweetness. They know exactly what they stand for and which emotions they must elicit. Once plugged into a socket, they have no qualms about reliably delivering what is expected of them.

But their self-knowing frees them, amazingly, to touch something more authentic about the sentiments they are supposed to represent. The birds of “Incubator,” for instance, sit on a grandmotherly crocheted doily, which we could take at schmaltzy face value.

Yet they manage to evoke, like Correnty’s garments, layers of meaning, including the comfort of roosting and home, the protectiveness of the father, the tenderness of the mother for her fragile young offspring, the inner glow of love. It leaves us confounded by daring us to like something we would normally dismiss as manipulative, exploitive and commercial.

Andrea Sulzer’s works are a surprise in the sense that they are conventional for an artist known for boundless experimentation with materials and techniques. At the same time, they are not at all surprising. Mother Nature has always been a major muse for Sulzer, and these paintings – of solitary figures in the woods, stylized foliage and conditions of light – hew closely to her interests.

During her career, Sulzer earned a degree in forestry sciences and illustrated books on marine and conservation biology. Though these works are not as naturalistically rendered and have the quality of quickly painted oil sketches, they nevertheless feel like chronicles of her surroundings.

This involves another interest of Sulzer’s – the elusiveness of memory, which is stored in our experience of the landscape. And here is where their connection to “Tenera” come in. They have an aura of Mother Nature’s stillness and constancy, which offer a healing backdrop for memory. These paintings are far from the pandemic, wars and political dystopia of humans’ making.

Two paintings are titled “sunlight, April 16, 2020,” one apparently done at 6:40 p.m. and one at 6:41 p.m. In both, the warmth and brightness of sunlight are visceral to the point that you can almost feel it on your skin. Even “getting dark,” exudes comfort thanks to the calmness of the central figure, who seems to take in the phenomenon of night falling as a cozy blanket being drawn over the world.

Finally, there are the works of Barbara Sullivan, which are small wall sculptures of folded shirts and jeans. They employ the technique of fresco, which applies water-based pigments to wet plaster. Sullivan has been widely exhibited and has taught fresco workshops around Maine.

Though I admire the revival of a venerated art that flourished during the Renaissance, I was not personally moved by these works. I understand the tenderness conveyed by clothing that is worn next to the skin, as well as the thoughtfulness of someone lovingly folding their (or someone else’s) laundry.

Perhaps it is their diminutive size and their emphasis on grandmotherly patterns like polka dots and tattersall plaids, which tilt them, at least for me, into something “crafty.” Unlike Rizza’s work, I didn’t feel a self-awareness that would give them more depth. I’m not saying they don’t have depth or value; I’m sure many viewers will like them, and art, of course, is subjective.

The only one that held more interest for me was titled “Tom Burckhardt.” That is because it relates to a particular person (I surmise it is the painter and educator on the faculty of Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting, who Sullivan likely crossed paths with there).

There’s something about the personalized nature of this title that grounds it with an air of commemoration, which does not happen for me with “Tattersall Twins,” “Blue Sisters” and other ambiguously named pieces. These titles concentrate on the superficiality of pattern and sweet notions of sisters, twins, etc.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story