To riff off an old adage, no artist is an island. Artists are impacted by their immediate surroundings, of course, but also by so much more.

Though Monhegan Island’s seclusion and natural beauty has attracted artists since the late 19th century – perhaps most famously George Bellows, Robert Henri, Rockwell Kent and the Wyeths – many of those who painted here also traveled extensively in Europe, primarily France, where they soaked up influences of the vibrant art movements sweeping the continent. They studied their craft at various schools under the tutelage of other famous artists, and they often bounced seasonally from one to another of the many art colonies that proliferated after the Civil War.

These colonies offered them a chance to socialize and paint with other artists and to take workshops with artists they admired, all leading to a rich cross-pollination of ideas and the further unfoldment of their personal styles. The particular artistic exchange between Monhegan Island and another thriving art colony 100 miles away, Cape Ann in Massachusetts, is the subject of the Monhegan Museum of Art and History’s “Cape Ann and Monhegan Island Vistas: Contrasted New England Art Colonies” (through Sept. 30).

Not surprisingly, the exhibition, curated by James F. O’Gorman, is primarily seascapes and harbor scenes. That could have been monotonous. Thankfully, the great variety of styles exhibited within this genre serve to chronicle a multiplicity of approaches that were informed by the great artistic developments happening during the show’s nearly 100-year timespan.

It all starts with a homecoming of sorts: a lushly rendered childhood portrait of Jacqueline “Jackie” Hudson by George Bellows, which a museum trustee purchased last year and bequeathed to the museum in honor of the institution’s director from 1984 to 2019, Edward Deci. Jackie Hudson helped found the Monhegan Museum in 1968, and Deci, a lifelong collector of Monhegan artists, certainly transformed it into what it is today, so Jackie’s return to the island holds special significance.

Jackie’s father, Eric Hudson – a painter, lithographer and photographer – had metaphorically opened the artistic floodgates to the island in the late 1800s when he chanced upon it during a sailing trip with two other artists. Impressed with the visual potential offered by the island’s dramatic cliffs and pine forests, he built a house near the harbor, where he painted during the summer months until his death in 1932. As word-of-mouth spread, this 4.5-square-mile mound of igneous gabbro rock flooded with other painters and sculptors.

Jackie was one of Eric’s two daughters (the other was Julie). She became an artist herself and, like all those represented in the show, also lived or painted in Cape Ann. The latter had become a thriving art colony in the late 1860s. The contrast between locations is apparent in the pairing of Jackie’s “Storm in Monhegan Harbor” and “Church Fair, Main St., Rockport.”

The former is a tempestuous, danger-filled scene that conveys the remoteness and isolation of Monhegan, as well as its susceptibility to the elements. The latter captures the livelier social community life of this peninsular Cape Ann fishing village. Though also removed from urban cacophony, it’s clear from the festive gathering here that we’re on the mainland, with Boston under an hour away. Both are painted in an impressionistic style.

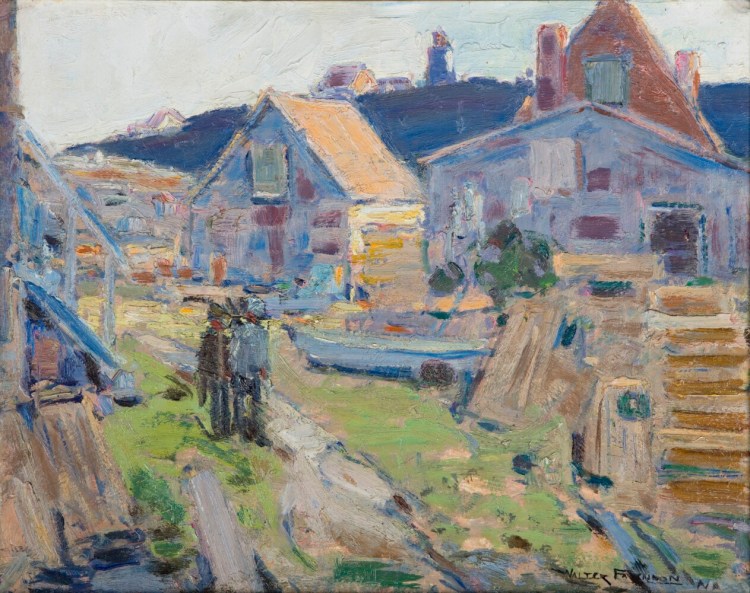

Walter Farndon, “The Docks, Gloucester, Massachusetts,” oil on board. Private collection. Image courtesy of Vose Galleries, Boston, MA

One of several revelations in the show is the juxtaposition of two works by Walter Farndon. Born in England, he began painting in the 1890s, when post-impressionism dominated the Parisian art scene. It’s clear he picked up the love of thick, pure application of pigment post-impressionists and their precursors, the impressionists, shared. But he also developed an energetic brushwork characteristic of the post-impressionists, particularly Cézanne. Farndon’s strokes – short, fat and heavily impastoed (some clearly applied with a palette knife and then scraped) – animate both “Road to Fish Beach, Monhegan” from the 1930s and “The Docks, Gloucester, Massachusetts” (not dated).

What is riveting about the pairing is the way Farndon could vary the thickness of the paint, the brushstrokes themselves and the palette to achieve different effects. The pastel hues, shortness of strokes and crusty impasto of “Monhegan” convey the rusticity of the structures and locale, as well as the exposure of the island, which sits in the middle of the ocean, to the sun. The more saturated palette, areas of more lightly applied paint and strokes that appear thinner and longer telegraph the bustle of the port, it’s stabilizing connection to the mainland, the more refined architecture (a large brick building) and the liquid reflectivity of the water.

James E. Fitzgerald, “At the Graveyard,” oil on canvas. James Ftizgerald Legacy, gift of Anne Hubert. Photo courtesy of Monhegan Museum of Art & History

It’s also interesting to see how artists changed over time. In James E. Fitzgerald’s “Back Beach Willows, Rockport, Mass.,” circa 1925, the artist was still committed to pretty impressionist scenes. But 40 years on, in “At the Graveyard” (1960s), that has been supplanted by high expressionistic drama. The composition is triangular in a baroque kind of way, the better to elicit the emotion of strong upward movement similar to the monumental Théodore Géricault masterpiece “Raft of the Medusa.” Fitzergald’s brush is bold, his color saturated, and the way he raked paint diagonally across the canvas makes us feel the pelting power of the downpour.

Maurice Freedman’s style, too, changed by leaps and bounds. “Rockport Quarry Dock” of 1933 is a realistic but loose representation of his subject and exhibits the brooding color palette of the era. But by 1968, the date of “Cathedral to the Sea,” Freedman had reached back to and fully embraced the analytic cubist style he had been exposed to by his teacher in Paris, André Lhote, in the 1920s, and later by Max Beckmann’s fractured planes and black outlines in the 1930s. Analytic cubism’s disassembled forms and multiple perspectives are as far removed from “Quarry” as could be, and the sky is reduced to a few simple bands of purple, blue and green.

Maurice Freedman, “Rockport Quarry Dock,” 1933, oil on canvas. Collection of Alan Freedman. Photo courtesy of Greenhut Galleries, Portland, ME

Other painters remained more consistent over time. Both of Paul Strisik’s paintings, “Evening Tide, Good Harbor Beach, Gloucester” (1974) and “Monhegan Pier” (1959) – two of the most beautiful works in the show – exhibit the same dexterity in conveying warm evening light. The later painting might at first appear more refined because of the realistically rendered rocks in the foreground. But as the eye travels toward the beach and horizon, his loose hand and washes of color are of a piece with the earlier picture’s impressionism.

There’s more than enough here to justify the 55-minute ferry ride from Port Clyde. Margaret Jordan Patterson’s colored woodcuts have an almost Japanese sensibility. Leon Kroll displays equal facility with seascape (“Sunlit Sea,” 1913) and landscape (“Eden Road, Rockport,” 1961). Naturally, of course, “Island Vistas” also provides a great excuse to visit stunning Monhegan Island – as if any excuse was needed.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story