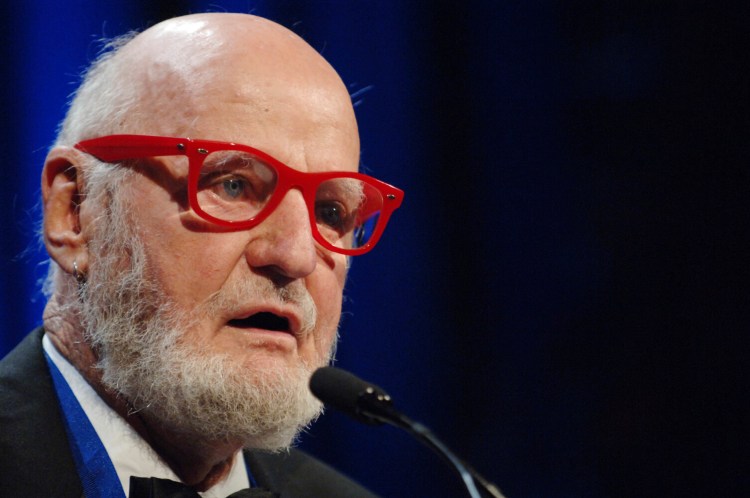

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, an acclaimed poet and longtime proprietor of City Lights, the San Francisco bookstore and avant-garde publishing house that catapulted the Beat Generation to fame and helped establish the city as a center of literary and cultural revolution, died Feb. 22 at his home in San Francisco. He was 101.

The cause was interstitial lung disease, said his son, Lorenzo.

Intensely private and fiercely political, Ferlinghetti became a household name in the 1950s when he stood trial on obscenity charges for publishing Allen Ginsberg’s hallucinatory anti-establishment manifesto “Howl.”

The trial brought attention from around the world for Ginsberg, his ecstatically irreverent poem and, by extension, the entire Beat Generation – a roving band of hipsters, poets and artists who rebelled against the country’s conservatism, experimenting with literary forms as well as with drugs, sex and spirituality.

The “Howl” episode also cast Ferlinghetti as a heroic defender of free speech and a stalwart friend of the creative fringe. In the resulting glare, City Lights became one of San Francisco’s most enduring institutions – at once a source for edge-of-mainstream books, a gathering place for the city’s wandering artists and a pilgrimage site for anarchists, radicals and liberal activists.

When not tending shop, Ferlinghetti retreated to the attic of an old Victorian house, where he had a typewriter and an expansive view of the city. He wrote dozens of books, including one of the best-selling poetry volumes in American history: “A Coney Island of the Mind” (1958), a plain-spoken, often wry critique of American culture.

Written to be performed aloud with a jazz accompaniment, “Coney Island” helped yank poetry from the academy into the streets.

“Christ climbed down/from His bare tree/this year,” reads one poem, “and ran away to where/no intrepid Bible salesmen/covered the territory/in two-tone Cadillacs.”

Poets Lawrence Ferlinghetti, left, and Allen Ginsberg sit with Stella Kerouac as she autographs one of her late husbands books, during the dedication of the Jack Kerouac Commemorative, a work of public art in Lowell, Massachusetts, historic district in 1988. Jon Chase/Associated Press

His own writing aside, Ferlinghetti was more widely known as a fixture at the center of the whirling counterculture that helped shape the nation’s social landscape since the 1950s. He was the bearded guru of San Francisco’s art scene, as closely identified with the city as summer fog and the Golden Gate.

He arrived in California in 1951 as a World War II veteran and a beret-sporting graduate of the Sorbonne. Within two years, he had helped open City Lights, a tiny shop that specialized in selling and publishing paperbacks and little-known poetry.

Located in San Francisco’s Italian-influenced North Beach neighborhood, City Lights quickly became the hangout of choice for the city’s radical intelligentsia, particularly Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso and the rest of the Beats. The doors stayed open until midnight weekdays and 2 a.m. weekends, and even then it was hard to close on time. From its earliest years, it stocked gay and lesbian publications.

“City Lights became about the only place around where you could go in, sit down and read books without being pestered to buy something,” he told The New York Times in 1968. “I had this idea that a bookstore should be a center of intellectual activity, and I knew it was a natural for a publishing company, too.”

Ferlinghetti inaugurated the publishing arm of City Lights with the paperback Pocket Poet series in 1955. Its first volume was his own “Pictures of the Gone World.”

Over the years, he sought outsiders and underground voices, and his little press gave early exposure to writers who would come to define a generation: Norman Mailer, Denise Levertov and, especially, the freewheeling Beats.

Ferlinghetti was clear-eyed about the fate of most avant-garde work. “Publishing a book of poetry is still like dropping it off a bridge somewhere and waiting for a splash,” he once said. “Usually you don’t hear anything.”

The reaction was much louder when he published “Howl,” a poem that enthralled him when he heard Ginsberg first perform it in 1955 at the Six Gallery, a converted auto repair shop in San Francisco.

“I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” Ferlinghetti wrote in a telegram he sent to Ginsberg later that night, echoing the words once written by Ralph Waldo Emerson to Walt Whitman. “When do I get the manuscript?”

The poem’s profanity and frank language about gay sex immediately drew censure when it was published in 1956. After its second printing, in 1957, Ferlinghetti and City Lights manager Shigeyoshi Murao were arrested on obscenity charges.

Anticipating trouble, Ferlinghetti had alerted the American Civil Liberties Union before “Howl” ever went to press.

Ferlinghetti did not testify at the trial, but he courted public opinion in the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle. “I consider ‘Howl’ to be the most significant single long poem published in this country since World War II,” he wrote. “If it is also a condemnation of our official culture, if it is also an unseemly voice of dissent, perhaps this is really why officials object to it.”

Ultimately, Municipal Judge Clayton Horn acquitted Ferlinghetti, ruling that the poem had “redeeming social importance” and thus could not be judged obscene.

That precedent was later used to defend books such as “Naked Lunch,” by William S. Burroughs, “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” by D.H. Lawrence, and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Capricorn” against obscenity charges.

The trial helped create a lasting impression that Ferlinghetti was one of the Beats, a notion he always shrugged off. He was older, he said, and more interested in tradition and technique – “the last of the bohemians rather than the first of the Beats.”

Lawrence Monsanto Ferling was born in Yonkers, N.Y., on March 24, 1919. He was the youngest of five sons of an Italian immigrant who shortened his surname upon arriving in the United States. (Lawrence would later reclaim the full name as an adult.)

The elder Ferlinghetti died of a heart attack before Lawrence was born. His mother, struggling to pay bills and disabled by grief, was institutionalized when he was a toddler. Ferlinghetti bounced among an uncle in Manhattan, an aunt in France and an orphanage in Chappaqua, N.Y. At one point, he was so malnourished that he developed rickets.

He was at once an overachiever and a delinquent, arrested for shoplifting the same month he made Eagle Scout. Eventually he went to live in a New York suburb with a wealthy couple who sent him to a private boys school, where his roommate introduced him to Thomas Wolfe’s autobiographical novel, “Look Homeward, Angel.”

Enthralled, Ferlinghetti chose to attend Wolfe’s alma mater, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He graduated in 1941 with a degree in journalism.

During World War II, Ferlinghetti served in the Navy and arrived in Nagasaki weeks after it was hit with an Allied atomic bomb. The scenes he witnessed were the root of his lifelong opposition to war and nuclear weapons.

“You’d see hands sticking up out of the mud,” he wrote, “hair sticking out of the road – a quagmire – people don’t realize how total the destruction was.”

With G.I. Bill benefits, he received a master’s degree from Columbia University, then lit out for Paris.

There, Ferlinghetti lived on the Left Bank, dwelled in cafes and wrote an unpublished novel and the dissertation for his doctorate in modern poetry. He also met his future wife, Selden Kirby-Smith, with whom he had two children before they divorced in 1976. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

He moved to San Francisco just as a bohemian arts renaissance led by the poet Kenneth Rexroth was beginning to draw notice on the East Coast.

“I used to make up all these literary reasons why I came out here,” he told his biographer, Barry Silesky. “But I realize it was really because it sounded like a European place to come. There was wine, and it just seemed more interesting in New York.”

He fell in with Rexroth, a pacifist who called himself a “philosophical anarchist” and who held weekly underground salons that sparked Ferlinghetti’s political awakening.

Much of his best-known work – such as the Cold War-era poem “Tentative Description of a Dinner to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower” – was infused with political argument.

He also protested against war and environmental destruction. He had no patience for poets who disengaged from the world to write.

“When guns are roaring,” Ferlinghetti once wrote, “the Muses have no right/to be silent!”

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.