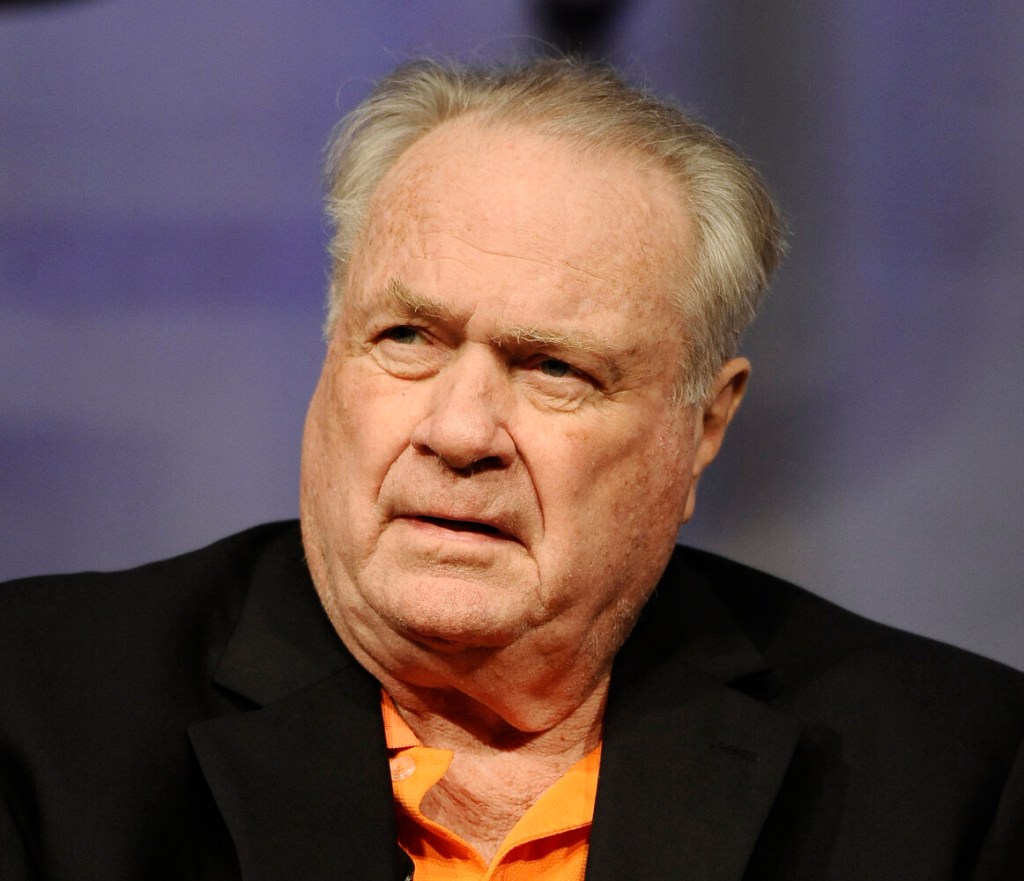

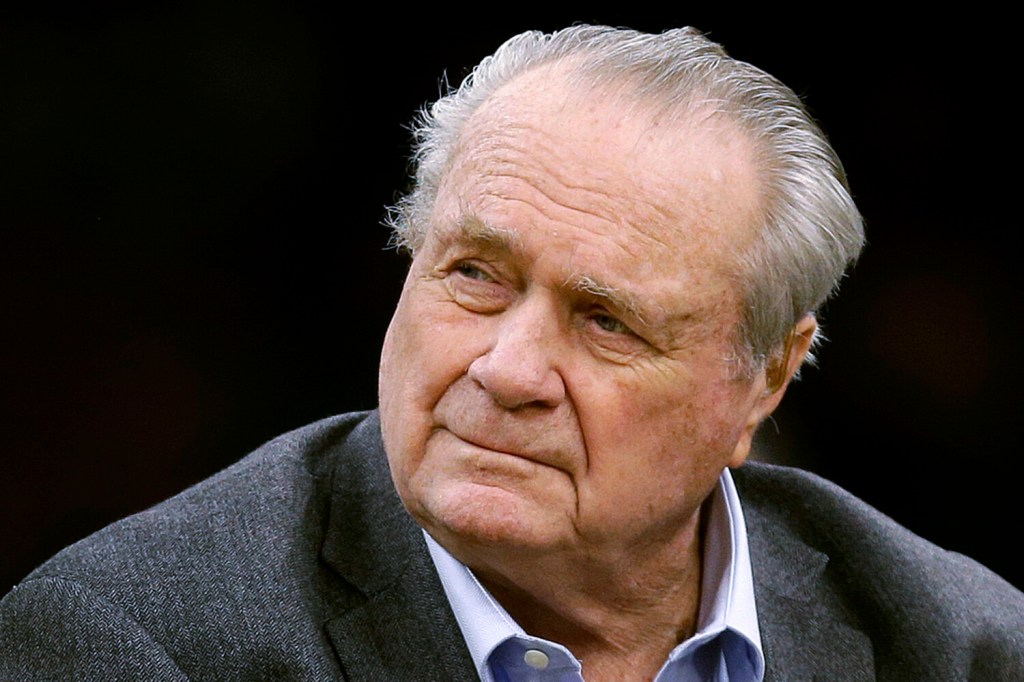

BOSTON — Tom Heinsohn, a Hall of Fame basketball star who was a cornerstone of the Boston Celtics dynasty of the 1950s and 1960s, and later coached the team to two NBA championships in the 1970s before a long career as a broadcaster, died Tuesday at his home in Newton, Massachusetts. He was 86.

His death was announced by the Celtics. He reportedly had diabetes and other ailments.

After a standout collegiate career at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, Heinsohn – who was often known as “Tommy” – joined the Celtics in 1956 as a first-round draft choice, winning the NBA’s Rookie of the Year award over his teammate Bill Russell.

Heinsohn, a 6-foot-7 forward, was the Celtics’ leading scorer for three years in the early 1960s, on a team that included such stars as Sam Jones, Bill Sharman, Bob Cousy and John Havlicek.

He sometimes clashed with Red Auerbach, the Celtics’ head coach and team architect, who criticized Heinsohn’s lackadaisical training habits. In the early 1960s, Auerbach said Heinsohn had “the oldest 27-year-old body in the history of sports.” Even as a player, Heinsohn smoked at least a pack of cigarettes a day. When he tried to quit, he gained weight – prompting Auerbach to suggest that he start smoking again.

Nevertheless, Heinsohn was a six-time all star and a powerful presence on both ends of the court, averaging 18.6 points and 8.8 rebounds per game for his career.

“Tommy has the greatest variety of effective shots in the league,” Sharman once said. “There are better shooters, I suppose, but Tommy’s agility and his exceptional body control gives him a big advantage.”

Cousy told the Worcester Telegram & Gazette this week that his old teammate was “the most underrated power forward perhaps in the history of the league.”

During Heinsohn’s nine seasons as a player, Boston won eight NBA championships. The winning ways continued after Russell succeeded Auerbach as coach in 1966, with the Celtics claiming 11 titles between 1957 and 1969. They were arguably the most dominant professional dynasty in U.S. sports history.

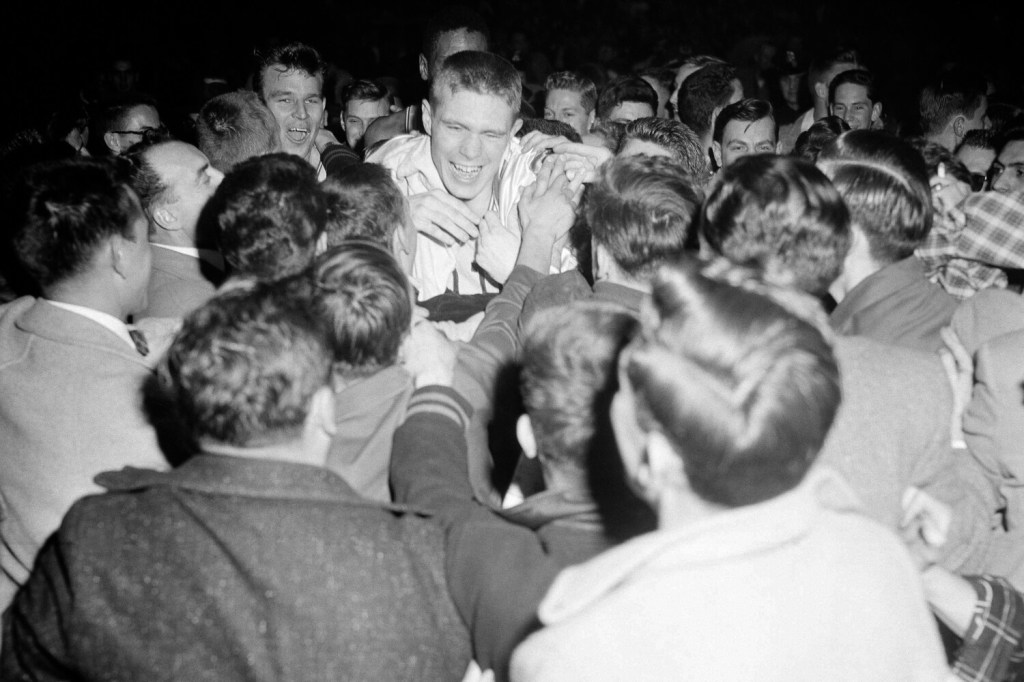

As rookie sensations together, Heinsohn and Russell led Boston to the team’s first NBA title in 1957, winning a seven-game championship series against the St. Louis Hawks. The final game, played at the old Boston Garden, was “one of the most thrilling finals seen in the history of the league,” wrote New York Times reporter William Briordy. “The action was so feverish that fans were left limp when the last buzzer sounded.”

The score was tied at 103 at the end of the regulation. After a five-minute overtime, the teams were still deadlocked at 113. With a little more than two minutes remaining in the second overtime, Heinsohn sank a long jump shot to put the Celtics ahead, 121-120.

Shortly afterward, however, he fouled out of the game. St. Louis tied the score, but two of Heinsohn’s teammates, Frank Ramsey and Jim Loscutoff, scored the final four points to secure the victory for the Celtics, 125-123.

Heinsohn led his team with 37 points and had 23 rebounds. Russell, a player he admired above all others, scored 19 points for Boston, with 32 rebounds and five blocked shots.

Seven years later, in a championship series against the San Francisco Warriors, who were led by 7-foot-1 Wilt Chamberlain, Heinsohn delivered another heroic performance. In the third quarter of the fourth game, playing with a cut over his right eyebrow, Heinsohn scored 15 points in less than five minutes to lead Boston to a 98-95 comeback victory. In the fifth and final game, Heinsohn led the Celtics with 19 points as they captured another title, 105-99.

Heinsohn retired after the 1965 season, making his final appearance in yet another championship-winning game. His No. 15 was retired by the Celtics, and he then worked as a broadcaster for the team before taking over from Russell as head coach in 1969.

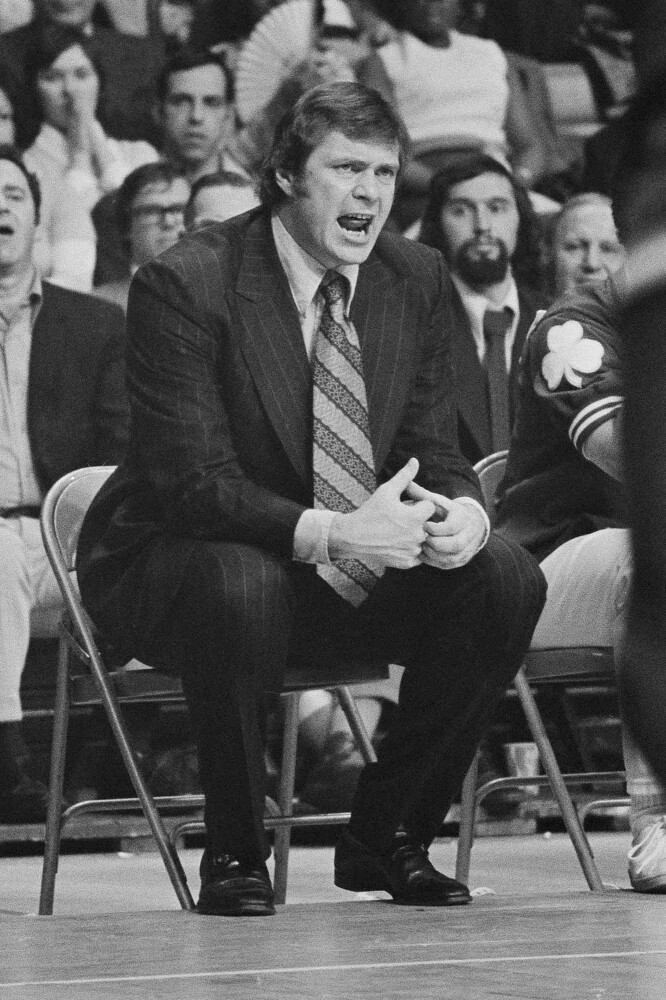

In Heinsohn’s first four seasons at the helm, the team improved, year by year, from 34 to 44 to 56 to 68 victories. The club’s 68-14 record in 1972-73, when Heinsohn was named the NBA Coach of the Year, remains the best in team history.

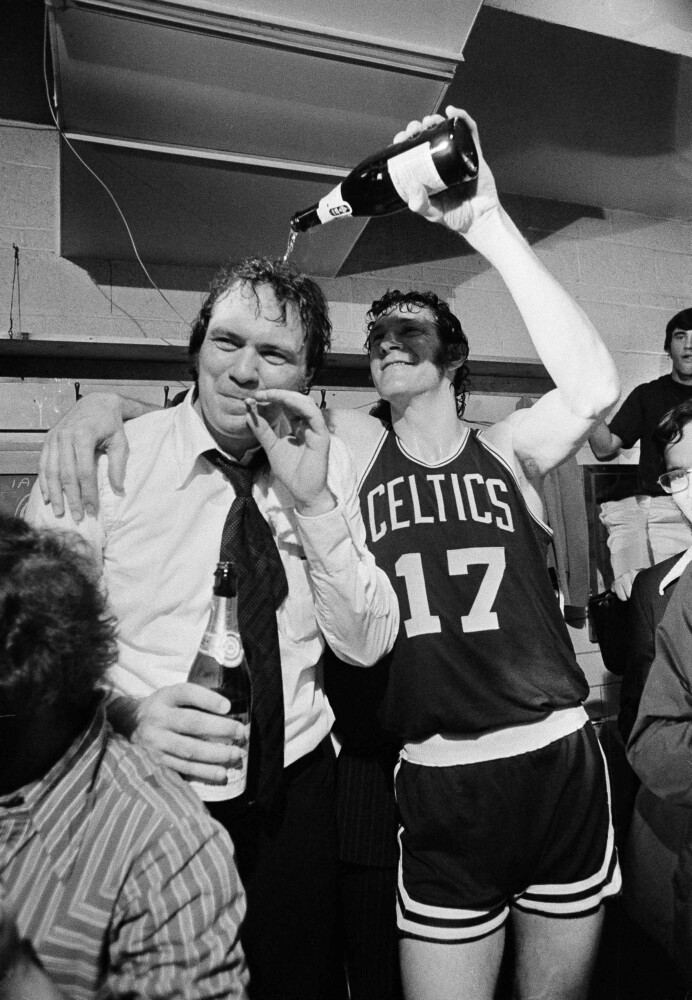

With star players Havlicek, Dave Cowens and Jo Jo White, Heinsohn restored the Celtics to their former glory, winning NBA championships in 1974 (over the Milwaukee Bucks) and 1976 (over the Phoenix Suns). He was fired midway through a losing season in 1978 and never coached again. He had a career record of 427-263, for a .619 winning percentage.

As a player and a coach, he advocated the same relentless style of play he learned from Auerbach.

“We ran whenever we could!” he told Boston.com in 2016. “We wore ’em out. They talk about pace today. We had pace and tempo, and we controlled it. During my tenure as a player and coach, that was always the secret weapon. Playing with pace.”

Heinsohn later went on to a long broadcasting career with Boston radio and television stations and also with CBS Sports. For more than 35 years, he teamed with play-by-play announcer Mike Gorman on Celtics local TV broadcasts. Heinsohn continued to deliver analysis and commentary until last year.

He seemed unconcerned when he was called a “homer,” openly favoring the team he had been associated with for six decades.

“People watching us are Celtics fans,” he told the Wall Street Journal in 2016. “They’re not Portland Trail Blazers fans.”

Thomas William Heinsohn was born Aug. 26, 1934, in Jersey City, New Jersey, and later lived in Union City, New Jersey.

He went to Holy Cross on a basketball scholarship and helped lead his team to the 1954 National Invitation Tournament title. He was named an all-American at Holy Cross, where he set scoring records and still holds all of the school’s rebounding records, including a single-game best of 42. He was a dean’s list student and graduated in 1956.

Heinsohn served as president of the NBA Players Association during his playing career and led a threatened strike, over players’ pensions and other issues, that delayed the start of the 1964 All-Star Game. His actions led the Celtics owner, Walter Brown, to label Heinsohn the “No. 1 heel in sports.”

Heinsohn had a successful insurance business for several years and was also a skilled painter, primarily of landscape scenes. He often exhibited his works in galleries, where they sometimes sold for thousands of dollars.

His marriage to Diane Regenhard ended in divorce. His second wife, the former Helen Weiss, died in 2008. Survivors include three children from his first marriage; a sister; and seven grandchildren.

Heinsohn was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame as a player in 1986 and as a coach in 2015. He is one of only four members of the hall – along with John Wooden, Lenny Wilkens and Sharman, his former teammate – to be enshrined as both a player and a coach.

Known as a fiery player and coach, Heinsohn was often combative toward referees. During the 1972-73 season, when he was named Coach of the Year, he was whistled for more than 20 technical fouls.

“I don’t hate them – honest,” Heinsohn said of referees in a 1976 Washington Post interview. “I have great compassion for them, although people may not think so. Where we run into problems is that my bread and butter depends on their judgment. And sometimes their judgment stinks.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story