COVID-19 has transformed our lives into a series of virtual experiences. In some respects, and depending on your perspective, this has been salubrious (i.e.: allowing us to work from home and spending more time with our family). In other cases, less so (allowing us to work from home and spending more time with our family). Seriously, though, “Site Specific,” the new show of Tina Ingraham’s work at Greenhut Galleries, presents a compelling argument for the need to view art – particularly painting – in person. There is no way to fully appreciate Ingraham’s oil-on-linen landscape and still life paintings on a computer screen. There may even be a risk of misinterpreting them entirely through this medium.

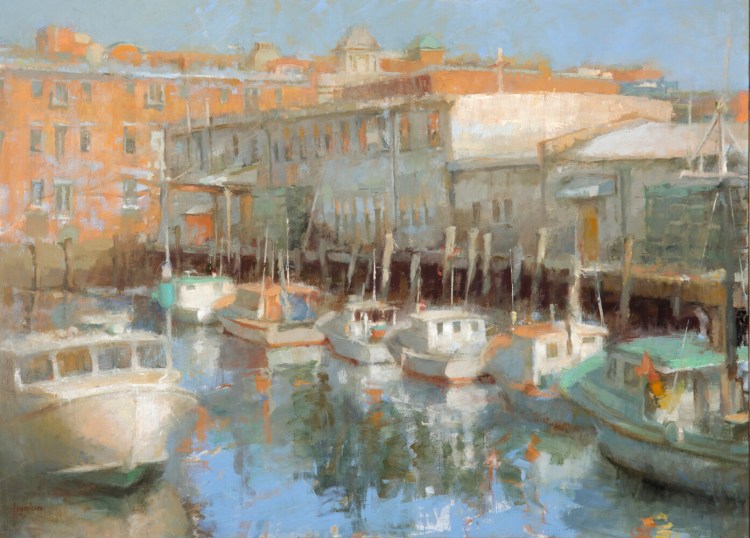

The reproductions of Ingraham’s work on the galleries’ website, for instance, give several of them a golden cast. Reading her bio reveals the artist studied for many years in Perugia, Italy, which could lead to the assumption that she is suffusing Maine scenes unnaturally with Umbrian light, in turn implying that these are overly romanticized works. That golden hue could feel inauthentic and overly sentimentalized, especially because the state’s clear, raw light is precisely what lured so many painters here throughout history. Though golds do tint the clouds in paintings such as “Portland Pier Moorings” and “Low Tide,” they do not permeate these images.

Which is not to say that Ingraham’s work is not unabashedly romantic. It is. Impressionistic, drenched in soft pastel hues, with outlines of trees, objects and buildings often blurred, they are thoroughly pleasing and visually undemanding. That is not everyone’s cup of tea, and certainly verboten for those who feel art should challenge the viewer or foment comment and controversy. But regardless of your taste, these works reveal a serious painter with an assured and skillful technique that sets Ingraham apart from many artists who engage in similar subject matter. For this reviewer, the success of this impressionistic approach is largely thematic.

In “Catching Late Afternoon,” artist Tina Ingraham captures the glinting reflectivity of water, as well as its sense of physical depth. Ken Woisard/Courtesy of Greenhut Galleries

In the case of paintings like “Embrace” and “Suspended Blossoms,” for instance, wispy brushstrokes and areas of thickly applied pigment that has been subsequently scraped off help convey the sensation of branches delicately stirred by a breeze. In “Catching Late Afternoon” and “Angled in Light,” they serve to simultaneously articulate the glinting reflectivity of water and its fluidity and sense of physical depth. When Ingraham paints country houses, however, as in “House and Fence” or “Old Colonial,” the romanticism can feel nostalgic and borderline greeting-card ready.

Fortunately, Ingraham deploys some techniques that keep the romanticism from carrying the image off into a gauzy, dreamily soft-focus fairy tale. Exhibition materials quote her as saying, “A look through a viewfinder divides my vision of the subject into fractions, and I clearly see where strong contrasts meet. I mark those on the canvas with charcoal.” Only then does she begin troweling paint on with her palette knife. This underlying architecture of the paintings stabilizes the potential idealism, giving the works a strong sense of form and composition.

The scrape of the palette knife can also leave scratched areas, and the variation in application – from thin washes of paint to crusty daubs – animate the surfaces with texture, imparting a corporal sensuality that elicits a visceral response from the viewer. Ingraham is also a perfectionist. These are by no means quickly dashed off. Gallery manager Roy Germon explained that years after painting a bowl of cherries that hangs in the show, Ingraham went back to refine the stems of the fruits.

Tina Ingraham’s “Low Tide” telegraphs the beautiful poignancy of nature at rest. Ken Woisard/Courtesy of Greenhut Galleries

The best paintings, subjectively speaking of course, are “Sand Flats” and “Low Tide.” They are not just deftly rendered. The large expanse of simple natural elements (water, marsh, sand and sky) somehow telegraph the beautiful poignancy of nature at rest. Nothing stirs; all is quiet and peaceful. The size of these also feels enveloping and embracing, helping us immerse ourselves in the landscape. Like the best Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings – Monet’s water lilies, Cezanne’s still lifes and his views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, Degas’ “The Absinthe Drinker” – there is an emotional dimension to the subjects that stirs sweetness and a subtle melancholy.

These two works alone are worth donning your mask and gloves and rubbing in a spritz of sanitizer to see them in the flesh.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story