Edna Lewis, or Miss Lewis as she was universally known during her four-decades-long kitchen career, is the original slow food, local food, farm-to-table American chef. She died in 2006 at almost 90 years old. In 2016, on what would have been her 100th birthday, “The Edna Lewis Cookbook” was reissued by Axios. The following year, an episode of “Top Chef” featured a challenge built around her recipes. After it aired, Lewis’ cookbooks shot up bestseller charts.

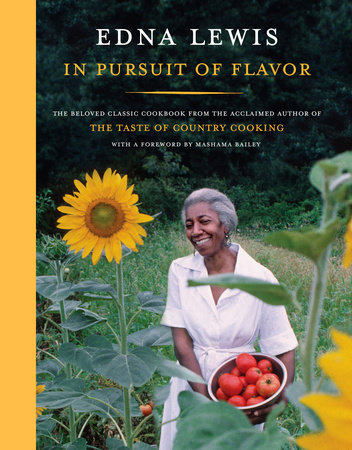

The “Ednaissance” continues with a 2019 reissue “In Pursuit of Flavor.” First published in 1988, it was the third of her four cookbooks and the follow-up to “The Taste of Country Cooking.” The latter was widely recognized for upending conventional ideas of Southern food by presenting it as complex, sophisticated and grounded in African-American foodways.

Both “In Pursuit of Flavor” and “The Taste of Country Cooking,” are nostalgic cookbooks. They capture a now vanished way of life that revolved around food, family and the earth. Lewis grew up in Freetown, a small Virginia community built by her grandfather and other formerly enslaved families after the Civil War. Life in a community of black sustenance farmers in the Jim Crow south must have been hard. But her memories are vivid, idyllic and pastoral.

“There was an old gent in the neighborhood who loved to fish,” she writes at the beginning of the chapter “From the Lakes, Streams, and Oceans.” (The cookbook is organized around food sources, like the farmyard or the griddle.) “This old gent would fish all morning and in the late afternoon, call out what he had for the mothers of Freetown to come pick up. He never charged anything for the fish. He fished because he liked to.”

With a local economy like that, it’s not surprising that Lewis identified as a Communist. One of her first jobs after moving to New York City was typing for the Party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker. When her cookbooks first published, Lewis’s food philosophies were considered radical as well – she advocated using the best, seasonally available ingredients; foraging; and reducing waste. These ideas were immediately embraced by cutting-edge California cooks, including Alice Waters, who was just then developing her Chez Panisse ethos.

For keen readers, Lewis’ cookbooks are the memoirs of a food obsessive. She makes her own jelly bags from Virginia ham packaging. She recalls the specific taste of the chestnuts from her grandfather’s grove. She writes that her favorite dessert from childhood was “snow cream,” made with snow that her father shoveled off their roof. The incredible collection of canning, preserving and pickling recipes features heritage fruits that hold up best, like canned Keiffer pears or green gage plum preserves.

Many of Lewis’ beloved recipes are made from just a few basic ingredients. Her shrimp and grits were famous for being just those two ingredients – plus pools of butter. But the seeming simplicity belies the effort. The most common element in Lewis’s cooking that’s not on the ingredients list is time. She used it to shop for heritage breed eggs; to forage for extra peppery, wild watercress; to let her cookie doughs dry out for 24 hours before being baked.

I cooked Lewis’ leek and potato soup for lunch. The recipe relies on a long sauté of potatoes, leeks and butter to build a flavor base. She suggests using your sense of smell to know when it is done – or 20 minutes. For me, the heavy cream to milk ratio made it too rich for a second helping, but the recipe was straightforward. I think Lewis would say I made a mistake by using store-bought chicken stock.

The facing page offered a recipe for cooking leek “leaves” that intrigued me.

“I really do not know why more people haven’t thought of cooking the green tops of leeks,” Lewis writes in the introduction to this recipe. Me too, Miss Lewis! I am agitated by leeks – although I love their taste, I mostly have avoided buying them because of how much was supposed waste.

It turns out that cooked leek leaves tasted like their wild cousin, ramp leaves, though more robust and spongy. Every last bit of this side dish was eaten up. Miss Lewis says to throw out the very tops, which I did, although now my editor admonishes me for not keeping them for that homemade stock the next time I make soup.

Steamed Leaves of Leek

The recipe is from Edna Lewis’ “In Pursuit of Flavor.”

Serves 4

1 bunch leeks

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon butter

½ teaspoon finely chopped garlic

Cut off the white part of the leeks and save for another use. Wash the leaves and drain them. They do not have to be completely dry. Cut away about 2 inches of the tops and the bright green part at the bottom. Slice what is left into ½-inch pieces. You should have about 4 cups.

Put the olive oil, butter and garlic in a heavy saucepan, and heat it until hot but not sizzling. Add the leek leaves and cover the pan. Lower the heat to medium and steam the leaves for 15 to 20 minutes. Serve the leek leaves as a green with meat or chicken.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story