Andrew Clements, a schoolteacher turned children’s author whose first novel, “Frindle” – about a mischievous fifth-grader who coins a new word for “pen” – was an unlikely bestseller about a kid’s power to shake up the classroom, if not the entire English language, died Nov. 28 at his home in West Baldwin, Maine. He was 70.

His wife, Rebecca Clements, confirmed his death and said the cause had not been determined.

Clements wrote more than 80 children’s books, including the text of picture books about a pampered Egyptian cat, an unbecoming fish, a Christmas in which Mrs. Claus stands in for Santa and a young girl who can’t stop using compound words such as nitwit, higgledy-piggledy and itty-bitty. That rib-tickling book was appropriately called “Double Trouble in Walla Walla” (1997).

Praised by author and New York Times reviewer A.J. Jacobs as “a genius of gentle, high-concept tales set in suburban middle schools,” Clements also wrote short novels such as “The Landry News” (1999), about an ambitious middle school journalist, and “The Losers Club” (2017), which featured a bookish protagonist who mirrored a young Clements.

“As a kindergartner . . . I confess that I was something of a showoff,” he once said. “I was already a good reader, and I didn’t mind who knew about it.”

Clements was best known for “Frindle” (1996), which was rejected by four publishers before being acquired by Simon & Schuster. It sold 8.5 million copies worldwide, was translated into 15 languages and emerged out of a talk Clements gave at a Rhode Island elementary school in 1990, when he pointed to a dictionary and told the assembled students that ordinary people had invented each of its words.

To prove his point, he pulled a pen from his pocket and declared that without anyone’s permission, they could start calling it, well, a frindle. “I just made up the word frindle, and they all laughed because it sounded funny,” he wrote on his website. “And then I said, ‘No, really – if enough other people start to use our new word, then in five or 10 years, frindle could be a real word in the dictionary.’ ”

Clements went on to use the example in school and library visits for the next few years, before turning it into a three-page picture book called “Nick’s New Word.” Editors told him it needed to be longer, so he expanded his story into a 112-page novel about a bespectacled boy named Nick Allen, who bedevils his teachers by lobbing “thought grenades” that derail their lessons.

Confronted with a dictionary-obsessed language-arts teacher, Mrs. Granger, he decides to channel his energy into a new project: Getting everyone in his classroom, and then in his school, to use the word “frindle” instead of “pen.”

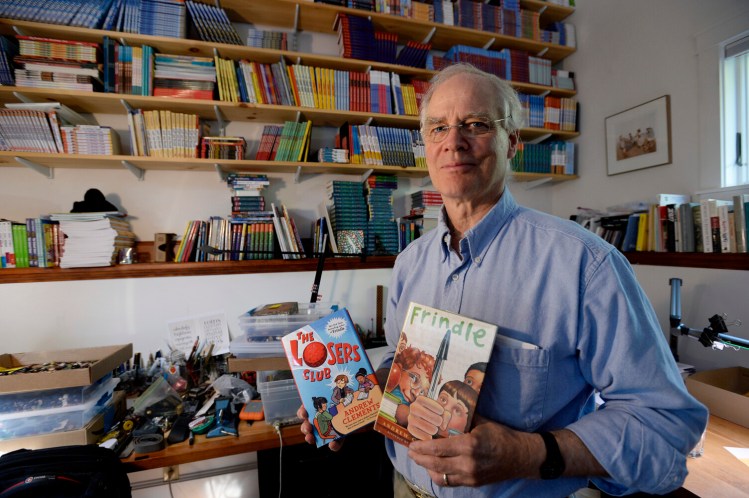

Maine children’s author Andrew Clements works in his home office in West Baldwin in 2017. (Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer)

“If there’s any justice in the world,” wrote a Kirkus reviewer, “Clements . . . may have something of a classic on his hands. By turns amusing and adroit, this first novel is also utterly satisfying. The chess-like sparring between the gifted Nicholas and his crafty teacher is enthralling, while Mrs. Granger is that rarest of the breed: a teacher the children fear and complain about for the school year, and love and respect forever after.”

Published with black-and-white illustrations by Brian Selznick, who later won a Caldecott Medal for “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” “Frindle” became a library staple and then an international hit, selling more copies overseas than in the United States.

It also received the 2016 Phoenix Award, given by the Children’s Literature Association for a 20-year-old book that has never won a major literary honor. And the word “frindle” (“rare, humorous”) was eventually added to Wiktionary, the free online dictionary run by the foundation that operates Wikipedia.

“It was one of those beautiful books that grew by word of mouth from the beginning,” said “Frindle” editor Stephanie Lurie. “People years later would say, ‘Oh it should have won the Newbery.’ We didn’t have those expectations for it, but we knew it had timeless themes – that words can’t be controlled or owned, and that words can change perceptions.”

The third of six children, Andrew Elborn Clements was born in Camden, New Jersey, on May 29, 1949. He lived in nearby Oaklyn and Cherry Hill until sixth grade, when his family moved to Springfield, Illinois. His father was an insurance salesman, his mother a watercolor artist and homemaker.

While studying literature at Northwestern University, he wrote occasional poetry, including a piece that he reused in his young-adult novel “Things Not Seen” (2002), the first in a trilogy involving blindness and (literal) invisibility.

A professor who liked his writing invited him to teach creative writing at summer workshops and, after graduating in 1971, he received a master’s degree in teaching the next year from National Louis University in Chicago. He then taught at public schools in the city’s northern suburbs, an experience that he described as “instrumental” to his writing.

In 1979, amid declining school enrollments in the region, he and his wife and young son moved to Manhattan, where he tried to launch a career as a folk musician, writing songs and playing guitar in the basement of their apartment building. When a demo tape drew little interest, he turned to publishing, joining Allen Bragdon, a firm specializing in how-to books.

He later joined Alphabet Press, an upstart children’s publishing house formed by one of his former students in Natick, Massachusetts, where he worked as a sales manager and editorial director – and published his first picture book, “Bird Adalbert” (1985), under the name Andrew Elborn. It featured illustrations by Susi Bohdal.

Clements worked as an editor with Picture Book Studio, Houghton Mifflin and the Christian Science Publishing Society before becoming a full-time writer with the success of “Frindle.” His other works included the children’s book “No Talking” (2007), which Times reviewer Lisa Von Drasek called his “best school story since ‘Frindle.’ ”

For decades, Clements wrote late at night, sitting down at his desk after 8 p.m. and sometimes continuing until daybreak. He used a garden shed (heated with a wood stove) in Westborough, Mass., before upgrading to a more spacious room next to his garage after moving to a Maine farm in 2014. Earlier this year he completed the first draft of a “Frindle” sequel, “The Frindle Files.”

“These stories, he had no idea where they were going,” his wife said. “He just had some kernel of an idea, and then slowly, slowly it would unfold, and surprise even him. Sometimes he would wake up in the morning and he’d roll over and say, ‘Don’t say a word,’ and he’d turn and start writing. . . . Toward the end of the book, he might as well have been in China – he was in another world.”

In addition to his wife of 46 years, the former Rebecca Pierpont of West Baldwin, survivors include four sons, John Clements of Johnson Valley, Calif., Charles Clements of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and George and Nate Clements of West Baldwin; two sisters; and three brothers.

Clements spent part of each day responding to fan mail and was often asked how he was able to write so many books.

“The answer is simple,” he wrote on his website: “One word at a time. Which is a good lesson, I think. You don’t have to do everything at once. . . . You just have to take that next step, look for that next idea, write that next word. And growing up, it’s the same way. We just have to go to that next class, read that next chapter, help that next person. You simply have to do that next good thing, and before you know it, you’re living a good life.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story