July is making up for the June gloom we experienced in a big way.

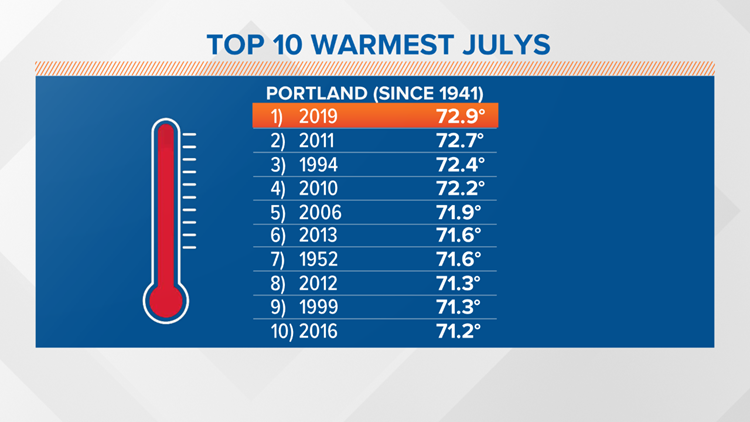

This month will go down as not only the warmest July on record in Portland, (72.9 degrees) but also the warmest month on record, besting July 2011 (72.7 degrees), July 1994 (72.4 degrees), August 2018 and July 2010 (72.2 degrees).

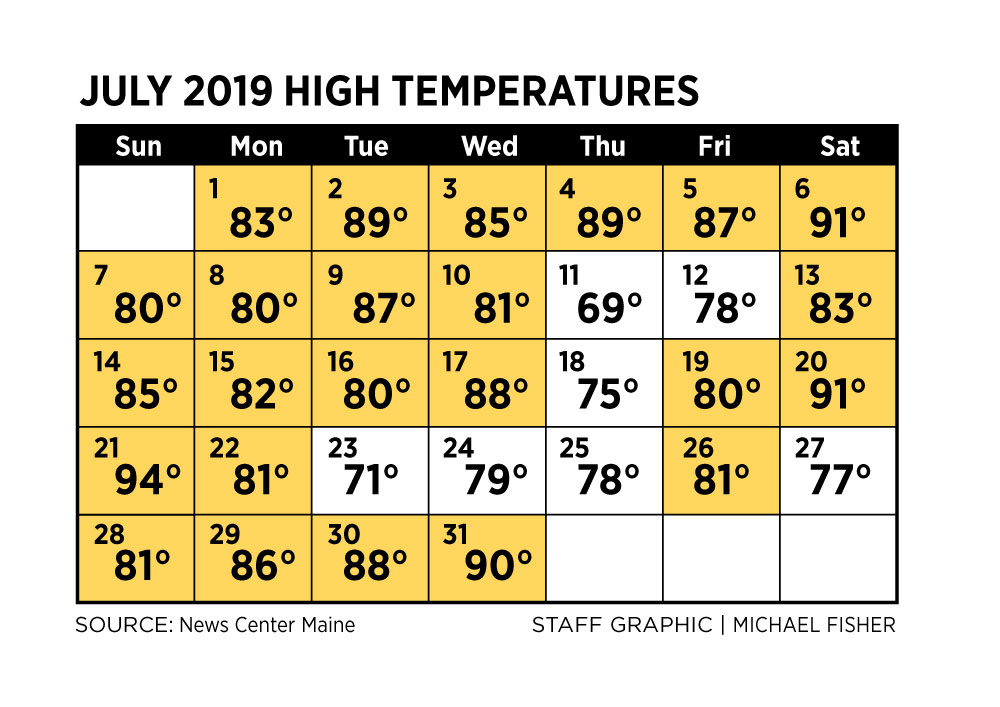

It’s interesting how we’re setting this record, because it hasn’t been remarkably hot, with the exception of the weekend in the middle of the month.

There have only been three 90 degree days; several Julys have had many more than that.

Instead, we’ve been consistently warm, a vast majority of the days a few degrees above average.

The nights have been much above average, however. Just looking at low temperatures in Portland, it’s the second warmest so far (and this morning could push it into the top slot).

There are a few contributing factors here: The well-understood urban heat island effect, in other words, the urban area of Portland retaining heat at night, unlike surrounding valleys which can cool efficiently on dry nights.

But the Gulf of Maine is much warmer than average this month; Casco Bay sea surface temperatures have consistently been in the mid 60s; some days the water has warmed to near 70 degrees.

In my opinion, the warmer ocean has an impact on the overnight temperatures in Portland. While it may cool off comfortably inland, any breath of wind off the water can keep the temperature up at night near the ocean.

This is one important connection to climate change: warmer oceans. While it’s impossible to say “this month is breaking records because of climate change,” the Gulf of Maine is warming and our changing climate is in the background.

In recent years, scientists have identified the Gulf of Maine as the second-fastest-warming part of the world ocean, and it has had dramatic effects on human and marine life alike.

An “ocean heat wave in 2012” caused lobsters to shed six weeks ahead of their usual schedule, throwing off the timing of Maine’s soft-shell harvest and leading to conflicts with New Brunswick fishermen over access to Canadian lobster processing facilities. The population of green crabs exploded, and they devoured most of the clams in Freeport, Brunswick and other towns, tearing up seagrass beds in many bays, while puffin chicks on Eastern Egg Rock starved because their parents couldn’t find appropriate food for them.

Last year, Gulf of Maine sea surface temperatures were 2.8 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, making it the third warmest year in the 37-year satellite record and triggering mass strandings of sea turtles in Massachusetts, and renewed concerns about the survival of endangered right whales, whose food sources are drying up in the heat.

The Gulf is experiencing this rapid warming because it is vulnerable to shifts in the relative strength of the frigid Labrador Current – which normally feeds the gulf – and the warm-water Gulf Stream, which can intrude when the cold current weakens. The Labrador Current is feared to be weakening as a side effect of the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, resulting in warmer water flowing into the gulf.

Our two warmest summers on record are 2016 and 2018. Now we’re setting a record for the warmest month, just one year later. Warmer and more humid summers are a symptom of our changing climate.

Reliable temperature records in Portland go back to 1941, so this will go down as the warmest on record in Portland.

We do have data before 1941, but it’s largely unreliable.

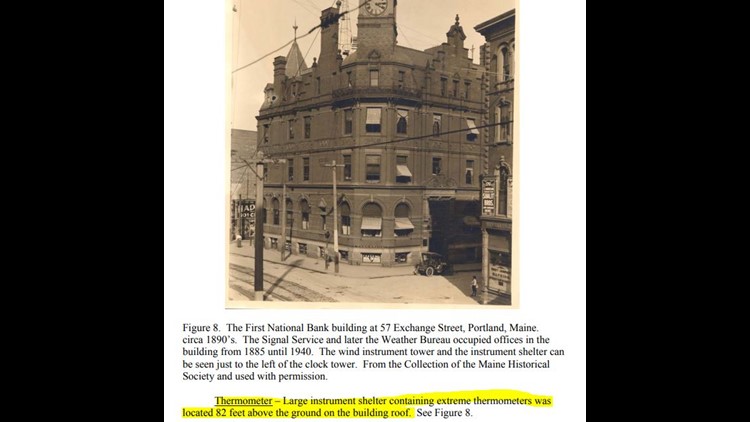

Before then, the observing site was all over the place — including for several years, on top of the “Weather Bureau” on Exchange Street. If you’ve ever been on a dark rooftop in the middle of the summer, there’s no need to explain how that could impact a thermometer’s readings.

There has been extensive research on Portland’s observation site through the years. Pre-1941 temperature data has been thrown out.

But even including those years, we may break the “faulty” records from 1876 and 1878; the July averages those years were 73.1 and 73.0 degrees.

That’s truly remarkable, given those records do not count, because the observing site had a significant “warm advantage.”

Comments are no longer available on this story