ROCKLAND — Jamie Wyeth glances at the paintings hanging on the gallery walls and sighs. “There’s a lot of baggage in these things.”

Grandson of N.C. and son of Andrew, Jamie Wyeth, who turned 73 on July 6, has stood as the inheritor of the Wyeth art legacy for a decade, since the death of his father in 2009. With the death of his wife, Phyllis, this past January, he stands alone apart from his art. In this time of personal loss and reflection, Wyeth is expressing the range of his emotions in a pair of summer exhibitions at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland.

“Phyllis Mills Wyeth: A Celebration” is what its title suggests: a celebration of a life. The paintings span more than 50 years, from before they were married, and capture the couple’s private moments: Phyllis asleep in her bed, riding horses and deliriously thrusting her face to the sky as she catches falling pollen in her open mouth, as if the pollen were falling snow. Glossed in an exuberance of spring green and yellow, the painting radiates abundant joy and temptation.

The exhibition is as close as Wyeth is willing to go in any public display of grief, and is as honest an expression of love and loss that he could make. He declined a public reception for the exhibition, and wants the paintings to speak for themselves. Most come from deeply personal places – the bedroom, the porch on their Monhegan home, looking seaward, and Christmas morning with the dogs. Wyeth portrays his wife with only a hint of the auto accident that left her disabled at age 20, before they met.

Jamie Wyeth points at a detail in his painting “Mr. Rockefeller on My Porch,” which is part of his series titled “Untoward Occurrences and Other Things.” Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

“I wasn’t going to have some funeral or memorial service. It’s all such bull (expletive),” Wyeth scoffed. “Better to have this be a statement than some preacher up there saying ‘Phyllis this’ or ‘Phyllis that.’ … I had forgotten I painted her so many times from the very beginning, when I first met her. I own all the work. A few of the paintings had been sold, and Phyllis started buying them back. Maybe she anticipated this.”

Wyeth’s tribute to his wife plays out in museums along the East Coast in 2019, with exhibitions in Maine, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. But the paintings of her – and other people from his life on display in a separate exhibit at the Farnsworth – tell as much or more about him. Coming at this moment of vulnerability, the work is strikingly personal and offers unusual insight into Wyeth’s journey as an artist and human being. It’s the stuff of a future art history class syllabus, a study of the last in a line of Wyeths whose paintings have influenced a century of American visual culture. Although Wyeth has relatives who paint, he and Phyllis had no children.

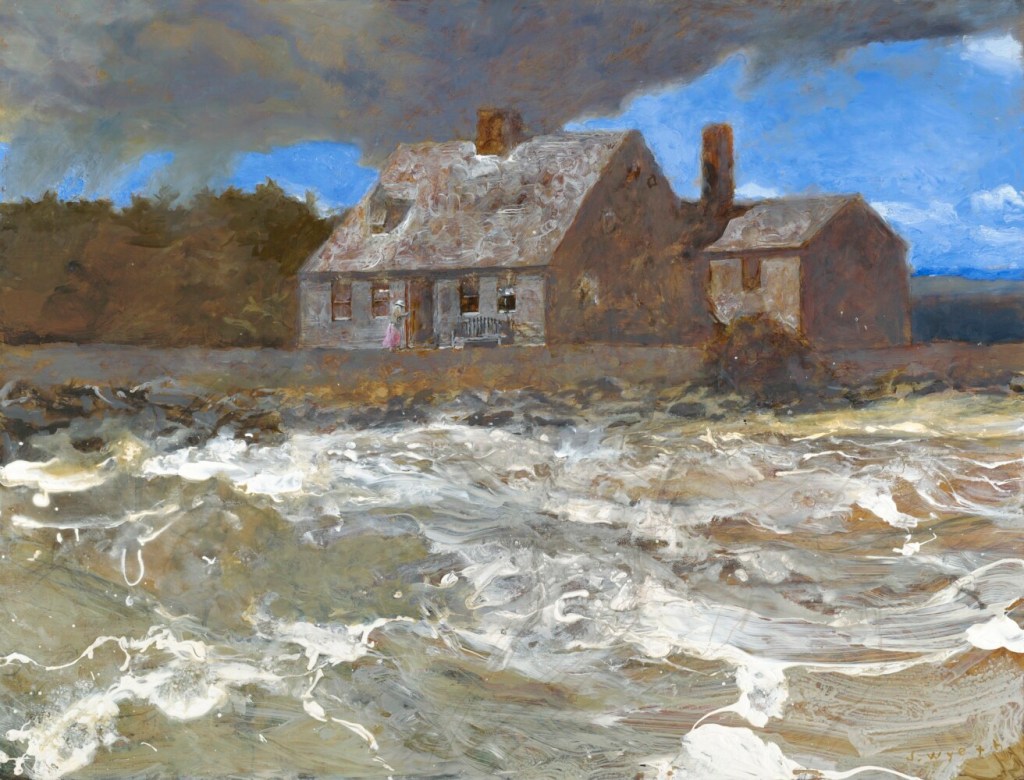

His mother, Betsy, is the other important woman on the walls at the Farnsworth, in the exhibition called “Untoward Occurrences and Other Things.” The understated and resonant acrylic, oil and watercolor “My Mother and the Squall” is Wyeth’s view of his mother outside her Benner Island home off Port Clyde. As seen from a distance on the water, where whitecaps bounce as a tempest builds overhead, the mother appears as a small figure at the front of the house, in a dress of pink, opening the door and ducking inside as the storm hits.

It’s a heroic image of a frail woman standing strong against time and the elements, independent and with dignity – just as he portrays Phyllis, but with an entirely different perspective. Wyeth paints his wife intimately, from their private moments looking out into the world. He paints his mother from a distance, from the outside looking in.

His mother is in poor health, he said, and is no longer able to travel to her island home in Maine from her home in Pennsylvania. This will be the first summer since she was a girl that she has not come to Maine. “She is 97 now, and it’s really difficult to have her on the island. It’s a very sad move, but she is happy in Chadds Ford. And so …”

He leaves his sentence unfinished and moves on to talk about another painting.

The ghosts are everywhere in “Untoward Occurrences and Other Things.” The exhibition is a collection of mostly new paintings and some deeply layered three-dimensional pieces. The paintings are based on Wyeth’s half-century of experiences on Monhegan and lifetime on the Maine coast, and he offloads a lot of psychology and personal history in this body of work.

With roots in Pennsylvania, Delaware and Massachusetts, three generations of Wyeths have painted in Maine. N.C. Wyeth became famous for his illustrations of books by Robert Louis Stevenson, but he was a fine-art painter at heart. He was captivated by the Maine coast during a visit in 1910 and a decade later purchased a home in Port Clyde, setting the family’s stake firmly in the midcoast a solid century ago. Andrew Wyeth found his inspiration on the islands and in nearby Cushing, where he made his best-known painting, “Christina’s World,” and where he is buried. Jamie Wyeth focused his attention on Monhegan and the islands.

Wyeth generally stays on Monhegan in the winter and stays away – on the mainland or in Pennsylvania – during the spring and summer to avoid crowds and gawkers, but he has come off the island for this interview at the beginning of the tourist season. His fingernails are caked with fresh blue paint, and he’s dressed for the studio, with mismatched socks and paint-flecked knickers. His hair, a mix of brown and gray, is windblown and wild.

It was a good boat ride, he said.

In Maine, the Farnsworth is the center of the Wyeth universe. Beyond showing Wyeth paintings, the Farnsworth operates the Wyeth Center, which generally focuses on the work of N.C. and Jamie, and a study center dedicated to Andrew. It offers tours of the Olson House in Cushing, where Andrew created “Christina’s World,” the iconic painting of a woman lying, torso twisted, in a field, looking uphill toward that same house. The museum opens the house to visitors seasonally.

With their paintings in Maine and Pennsylvania, the Wyeths have captured the public imagination for more than a century: N.C. seemingly most interested in the heroism and hope of early 20th-century America, Andrew focusing on the mysteries and personalities of people and place, and Jamie pursuing his fascination with animals, eccentric people and wild, stormy environments.

In a confluence of generations, the art of all three is being considered and reconsidered by the American public. The Portland Museum of Art will open a major N.C. Wyeth exhibition this fall, with a focus on both his illustrative work and fine-art pursuits, and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, will open a new wing in September that will feature a large map of the world that N.C. Wyeth painted in 1923, titled “Peace, Commerce and Prosperity.”

Ten years after Andrew Wyeth died, critics and the public continue to reassess his paintings and reshape the narrative of his story, placing him and his artwork in the context of rural American life and its related psychology. Jamie Wyeth remains as productive as ever, pursuing new ideas and experimenting with sculpture, media and themes. In his own right, he’s been in the public eye more than a half-century, when at age 20 he painted a portrait of the late John F. Kennedy. As recently as 2017, he had a high-profile exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Wyeth next to his painting of Andy Warhol, which is part of his series titled “Untoward Occurrences and Other Things” at the Farnsworth. Wyeth has two exhibitions of his work up at the museum, one of newer paintings and the other of paintings he did over the years of his late wife, Phyllis Mills Wyeth. Staff photo by Brianna Soukup

Wyeth seems to have had fun making this current batch of Monhegan paintings. They show his dark humor and are filled with energy. Chaos and mayhem hover over much of this work. He talks quickly as he moves around the gallery, excitedly pushing his face close to the paintings to show a detail – and to critique his work. Looking at a painting he made of David Rockefeller seated at his porch on Monhegan, he’s not sure if he succeeded in building up the textural quality of the paint as he had hoped to suggest the raging seas, but he enjoyed trying. “I am a terrible technical painter, so I am always trying strange things,” he said.

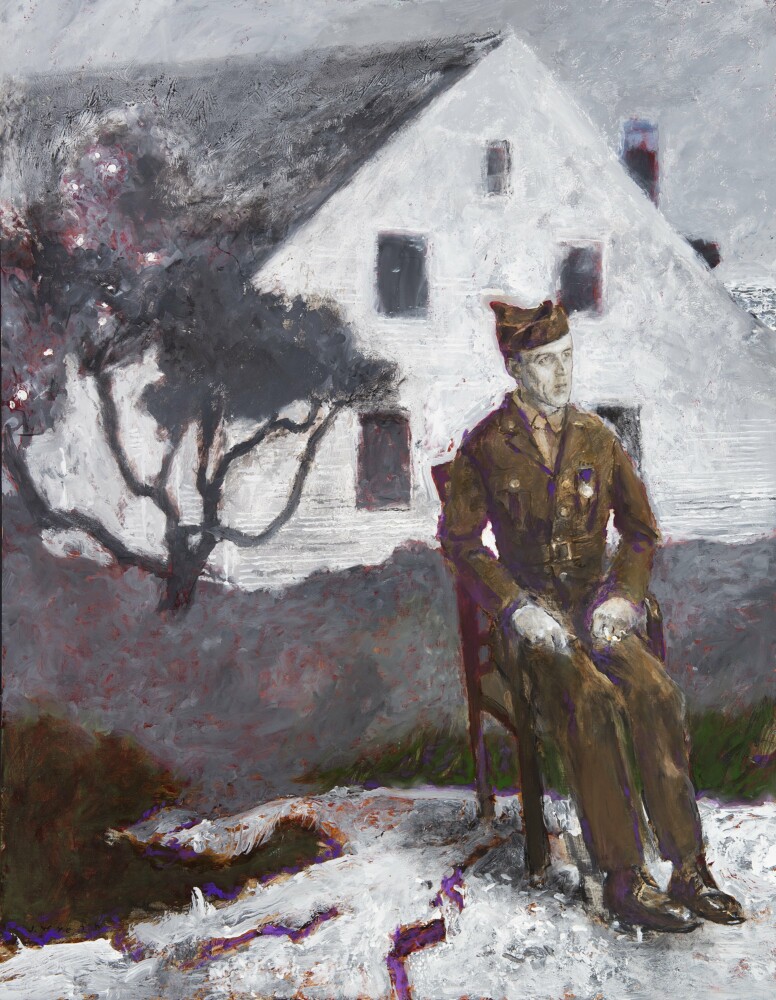

“Untoward Occurrences and Other Things” is an exhibition of heroes, mostly, and characters. In addition to his mother, Wyeth paints many important people in his life and in island life. The roster of luminaries includes Monhegan shopkeeper, D-Day invader and German POW Henry Odom, in a ghostly pose that Wyeth made from memory; the image, from life, of David Rockefeller, then 97, on the porch of Wyeth’s island home reading an e-book amid billowing winds; and the painter Rockwell Kent, whom Wyeth reveres and knew through an exchange of letters, and whose Monhegan paintings he collects and champions.

Wyeth’s life is entwined with Kent’s. In addition to collecting Kent’s paintings, Wyeth also owns one of two houses that Kent built on Monhegan, overlooking Lobster Cove. The structure, simple but dramatic with its location close to the sea, shows up in both Wyeth shows this summer – and often in other artists’ work. Maine painter Tom Hall is showing a silhouetted vision of the Kent-Wyeth house at Cove Street Arts in Portland.

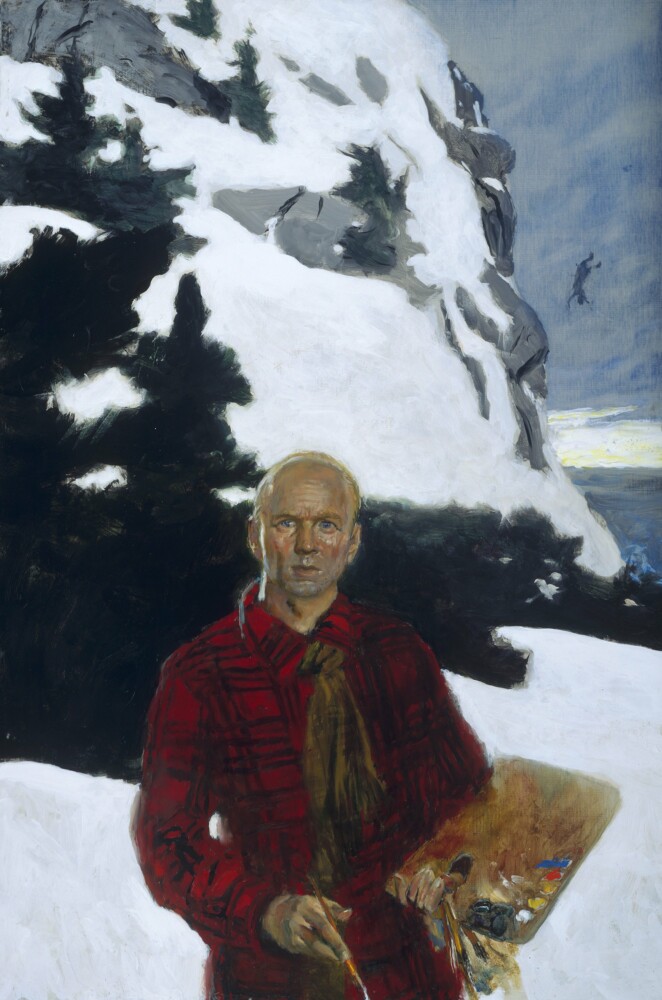

Wyeth’s painting at the Farnsworth shows Kent looking straight on in a red flannel shirt, easel in one hand, brush in the other. In the background are the snow-covered cliffs of Monhegan and a dark figure plunging off the edge, headfirst into the rocks and water below. It’s not fantasy or a dream, as Wyeth often paints. He based the painting on the death of Sally Moran in 1953, though her death occurred in the summer. She was living in Kent’s home, and they were rumored to have had an affair.

On July 1, 1953, the painter appeared before U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s Senate subcommittee investigating communism. When Kent refused to say if he was a member of the Communist Party, the public soured on him. Just over a week later, on July 9, Moran went missing. Her body was found floating in the ocean three weeks later. Kent was shunned on the island, and he never returned after that summer.

That’s the macabre story Wyeth chose to tell of one of his painting heroes. It represents the low point of Kent’s time in Maine – and that dark humor. There’s no artist in the world whom Wyeth admires more than Kent, primarily because of the paintings Kent made on Monhegan during his early residency, from 1905 to 1910. Wyeth cares much less about the Monhegan paintings Kent made later in his career, around the time of Moran’s death.

“He’s the one who brought me to Monhegan,” said Wyeth, who has pledged his collection of Kent paintings to the Monhegan Museum, which will share them with the Portland Museum of Art. “To me, he’s the only painter who has ever worked out there. He did things out there that are just extraordinary. The fact that he came to Monhegan as a young man, and he wrote how he couldn’t sleep at night he was so excited about the island and painting and so forth.”

It’s odd that Kent was turned out on the island after being associated as a Communist, Wyeth said, because it was on Monhegan where Kent became interested in the common good of the community. Kent was one of the few artists who lived there year-round. “He wrote a letter to two women that he knew on the island and said, ‘How can I paint the fishermen if I don’t fish? How can I paint the houses if I don’t build them?’ And it was this sort of social consciousness that I think took over.”

Most of Kent’s best paintings are in Russia, Wyeth said. Many years ago, Wyeth explored the possibility of bringing Kent’s paintings back to the United States, and he took his case to the top of what was then the Soviet Union. “At one point, my father and I met with (Soviet leader Mikhail) Gorbachev, if you can believe it, in Washington to talk about just that. His point was, he wanted (the work of) Russian painters to come to America. Why would he want an American painter to come back to America? There has been lots of talk, but they’re somewhat reluctant. Who knows?”

The other looming presence is the pop artist Andy Warhol. Wyeth knew Warhol for 10 to 15 years in New York, and Warhol gave Wyeth studio space in The Factory, Warhol’s studio that housed a collective of rotating artists. In this exhibition, Wyeth portrays Warhol larger than life as a painted figure emerging from behind a screen door, which is open into the gallery. Warhol is holding his dog, and the door is painted with stars and stripes.

During this interview, Wyeth offered to step inside the roped-off area of the Warhol piece to pose for a photo, then quickly apologized when a visitor turned up, and stepped out with an embarrassed laugh.

It’s called “First in the Screen Door Sequence.” He made another of his father peering through a dormer window, with his hand reaching through broken glass. He made a cast of his father’s hand for the piece. He made another of the actor Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.” He painted Peck behind the door with the character Scout.

That piece, he said, is owned by Walmart heiress Alice Walton, who has promised it to the museum she founded, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. “She keeps it in her house,” Wyeth said. “She says she wants Scout and Atticus in her living room.”

Wyeth knew Peck, who died in 2003. “He collected my work and whatnot. Whenever we would meet, I asked him about that film and working on it. It was an extraordinary role.”

He’s working on another in the screen door series of his grandfather. In addition to Kent, Wyeth also is a big champion of his grandfather’s work, but says he can’t compete with the big-money buyers in the art market. “I’m always butting heads with Steven Spielberg and, my God, the producer – what the hell is his name, who did ‘Star Wars?’ ”

George Lucas?

“Yes, George Lucas. If there is an N.C. Wyeth, they’ll pay anything.”

And if there is an overarching theme to these paintings beyond love, loss and the ghosts of past, present and future, it is the hope that follows a storm. Wyeth fills his surfaces with the yellows, oranges and reds of a Monhegan sky. A closing image is what he calls “Self-Portrait – Eighth in a Suite of Untoward Occurrences on Monhegan Island.” Wyeth made the painting in 2016, when Phyllis was declining.

He paints a respected island inhabitant, a feisty gull, standing guard as he sits on a rock and gazes into a glowing red sky that offers only the promise of tomorrow.

Paintings by artist Jamie Wyeth of his late wife, Phyllis Mills Wyeth, at the Farnsworth Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story