Comedy, it’s been said, is tragedy plus time. Is there any better evidence of this proposition than “The Producers?”

Written and directed by Mel Brooks and overflowing with Jewish talent on both sides of the camera, the 1967 film tells the story of a has-been Broadway producer and his timid accountant, who come up with a clever way to make a killing – as long as they can find a surefire flop.

Their ticket to paradise is a play about the sunny side of Hitler, which they stage with an unforgettable production number that is surely one of the funniest segments in the history of cinema. The “Springtime for Hitler” set-piece is a surreally lush parody of so many vintage Broadway musicals, and the choreography includes a Busby Berkeley-style aerial view of Nazis formed into a rotating, goose-stepping human swastika. The obscenely hummable music accompanies such lyrics as:

“We’re marching to a faster pace

Look out, here comes the master race”

I rewatched it recently and literally wept with laughter. But perhaps not just laughter. For “The Producers,” remember, was made a mere 22 years after the liberation of Auschwitz. It represents not just Mel Brooks at his outrageous best (and, sometimes, worst), but the triumph of a people ready at last to dance on the grave of their persecutors.

The making of “The Producers” is one of the most interesting parts of Patrick McGilligan’s highly detailed but disappointingly pedestrian new biography of Brooks, who comes across in this lengthy account as – let’s not mince words – a brilliant, insecure, grasping, credit-hogging boor. A domestic example: McGilligan reports that he gave his first wife an allowance of just $3 a day and betrayed her almost continually with other women. After they divorced, the author tells us, he let her and their three children fall into financial straits.

Born Melvin Kaminsky in 1926, young Mel lost his father when he was just 2, an event that left the four young Kaminsky brothers and their determined mother to struggle along without him through Depression, war and the world’s palpable hostility. But little Mel grew up in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg section, in a Jewish culture so pervasive it was practically in the air he breathed. Like his father’s death, it would condition his outlook, his humor and his creative choices for the rest of his life.

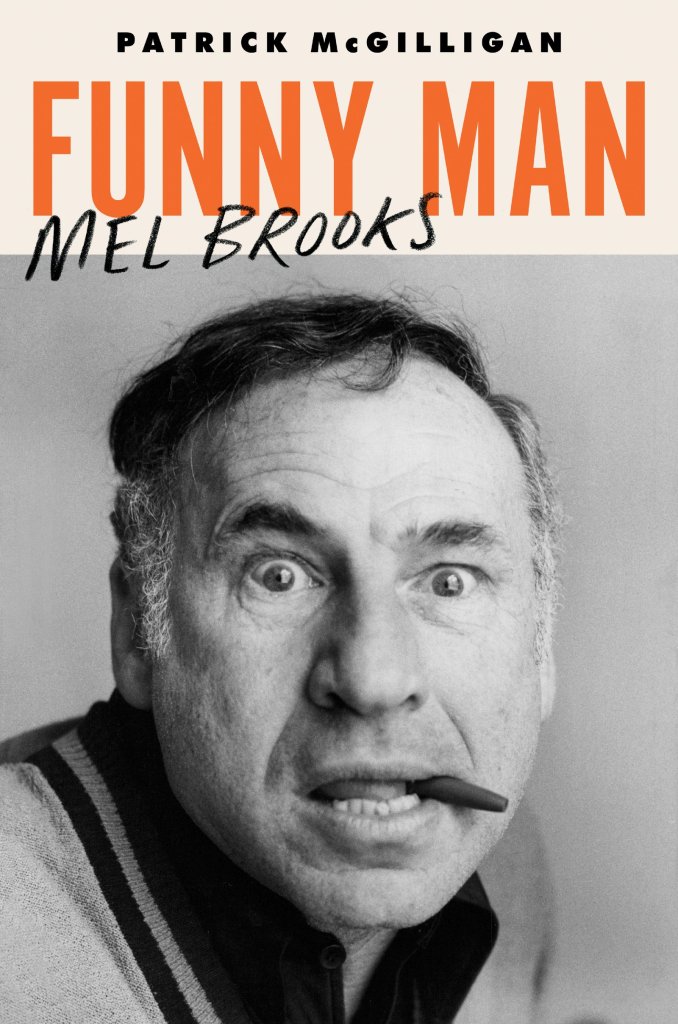

A veteran showbiz biographer, McGilligan is an awkward writer, a limited student of human psychology and not particularly insightful about Brooks’ work. Yet “Funny Man” still manages to be a pretty interesting book. It will have to do for now.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story