Here is a sentence you would not expect in a review of a book on one of the country’s most notorious school shootings: “Parkland” by Dave Cullen is one of the most uplifting books you will read all year.

The United States is a nation pocked daily by gun violence; we are a nation desensitized by the magnitude of our national bloodshed, a place where there are people – multiple people – who are survivors of multiple mass shootings. In an era of Donald Trump and social media, we are also meaner, reactionary, deeply cynical, depressingly divided. At a time of such national exhaustion, a book about a school shooting may not be the one you’re inclined to pick up off the shelf. Do it anyway. “Parkland” is a balm.

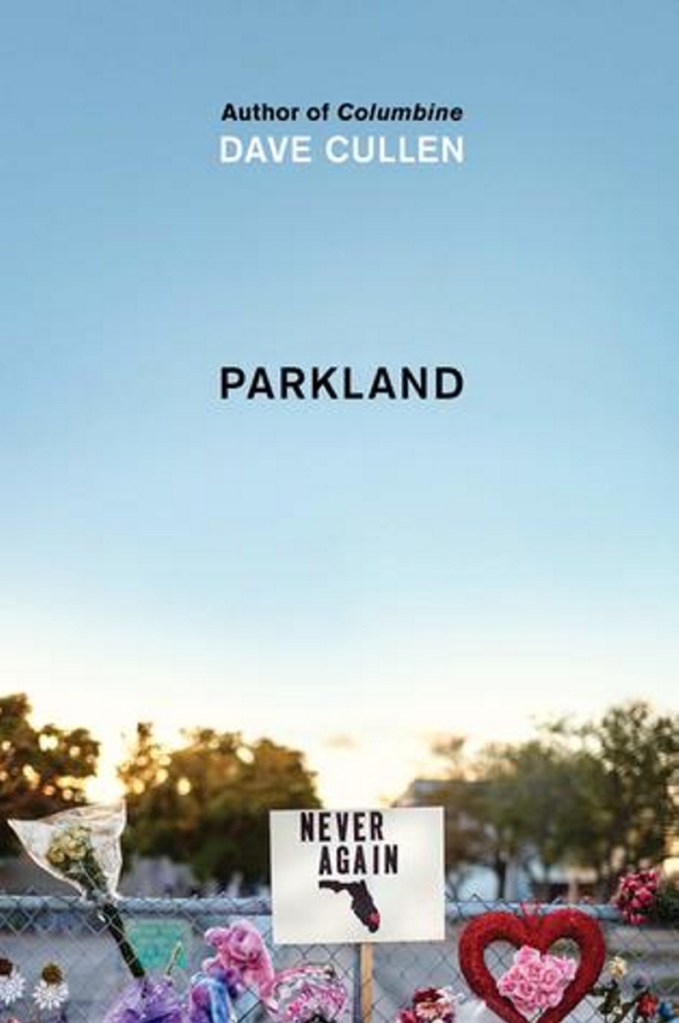

Cullen, also the author of “Columbine,” has with “Parkland” carved out a macabre niche as the country’s premier chronicler of mass school shootings. But “Parkland” is anything but dark. Very little of the book focuses on the 6 minutes and 20 seconds on Feb. 14, 2018, when a gunman walked into Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and killed 17 innocent souls. Instead, Cullen tells us what came next.

You know this story, but you don’t. You have probably heard of the main players or seen their faces on television or read their missives on Twitter: Emma Gonzalez with her big eyes and shaved head first calling out the many enablers of gun violence. David Hogg, a quick wit in 140 characters, taking on Laura Ingraham and the right-wing news machine. Cameron Kasky sending Marco Rubio stammering and stumbling over National Rifle Association money. The March for Our Lives, one of the biggest rallies in American history, when Gonzalez gave a brief speech and then stared down the camera, tears streaming down her face, for four excruciating minutes – Was she breaking down? Cracking up? – before finally saying: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and 20 seconds. … Fight for your lives before it’s someone else’s job.”

Cullen was there for these moments, but he also describes the before, when Hogg, after surviving the shooting, rode his bike back to school to document the events as a journalist; when Jaclyn Corin, an organizational mastermind trapped in the body of a petite, soft-spoken high schooler, marshaled buses of students to head to Tallahassee to convince legislators that gun violence was a scourge worth fighting; when a ragtag group of drama nerds and student journalists got together in Kasky’s living room, kicked out all the parents and decided something must be done. In Cullen’s telling, the uprising was fast, organic and initially diffuse. The genius of the Parkland students came in coalescing around a highly disciplined core group while letting other branches grow where needed.

For a politics-hardened reader, stories of earnest activism and kids changing the world are boring at best, insultingly cliche at worst. Cullen deftly navigates what could have easily been a sentimental and patronizing story (not to mention a tedious one). He takes us shoulder to shoulder with his subjects, through their victories and their errors, drawing out the bits of their personalities that are flattened out on a TV screen – Hogg isn’t angry but is a surprisingly good mediator of tense situations; Gonzalez is both ethereal and tactical, a force Cullen calls “the head and the heart.” Both are just teenagers.

Cullen brings us a large cast of characters, spending more time on the central players but touching on the double-digit list of people who made the March for Our Lives the movement it became: those who worried for a group of kids who flew forward full-bore, and those who were spurred to their own actions after the Parkland shooting. Cullen does not bore us with banalities or mawkishness. He manages to use the word “resilience” only once.

Parents play virtually no role in the Parkland kids’ organizing, other than offering role-appropriate demands for chaperones, mental health counseling and sleep. But they do serve as a kind of Greek chorus to Cullen’s hero narrative of the students. We see, from his telling, why adults made more risk-averse by experience (and brain development) could never have built this movement, which required risk-taking as much as naivete and determination. Where the voices of the adults do creep in, they are crucial reminders that this is fundamentally a story about children – brilliant, fabulous, preternaturally mature children, but children nonetheless. “I’m terrified,” Gonzalez’s mother, Beth, tells Cullen. “It’s like she built herself a pair of wings made out of balsa wood and duct tape and jumped off a building. And we’re just, like, running along beneath her with a net, which she doesn’t want or think that she needs.”

Among the most affecting are Manuel and Patricia Oliver, whose son, Joaquin, was killed in the shooting. “Tío Manny” becomes one of the only adults the kids will let into their work; he also works on his own, painting enormous murals he calls his Walls of Demand, then taking a sledgehammer and punching one, two, 17 holes in each one. Inside the holes he places sunflowers, part metaphor and part memorial: On his son’s last day on Earth, he brought Valentine’s Day sunflowers for his girlfriend, Victoria. After Joaquin’s death, Cullen writes, “Tori split the flowers in half, sealed them in epoxy, and made a necklace each for Patricia and Tío Manny, which they hold dear.” Joaquin, Tío Manny insists, is right there, not a victim but a leader of this movement. “Parkland” is a story of large-scale action. It is also a story of art, of creating beauty and ruins, and of many, many small kindnesses.

But the real genius of “Parkland” isn’t that it’s an inspirational tome. Instead, it’s practically a how-to guide for grass-roots activism. And most important, Cullen, and the students he writes about, situate this movement as one place on a longer historical arc toward justice. Early on, the Parkland students decide to make their quest about more than the suburban school shootings that dominate the news; they find common cause with teenagers in cities who face endemic violence not inside the classroom but often on their way to it, and whose realities are shrugged off as a predictable outcome of living in “bad” neighborhoods.

The most significant turning point in the story is when the Parkland students meet kids from Chicago who run similar anti-violence organizations, one called BRAVE (Bold Resistance Against Violence Everywhere) and one called Peace Warriors. Peace Warrior Executive Director D’Angelo McDade, then a high school senior in Chicago, introduces the Parkland kids to Martin Luther King Jr.’s principles of nonviolence, a framework that profoundly reshapes and guides their work going forward.

Later in the story, when the Parkland students are on a national tour, they refuse to be interviewed in Chicago unless a local kid is interviewed with them. And what the Chicago kids want is heartbreakingly simple. “I want to see happiness in my community,” says one Peace Warrior, Alex King. “I want to see the next generation, I want to see them being able to play outside. Being able to sit on the porch and nothing happen to them. Being able to go to their neighborhood park, being able to go to a friend’s house. Being able to go to church. Being able to go to school and be safe. I want to see that joy.”

These are the most resonant moments of “Parkland”: When we hear the students themselves. Luckily, Cullen is an adept storyteller, synthesizing a cacophony of voices and using his own simply to carry a reader cleanly through. He reacts to the story and the characters along with us, at times concerned, often awed, sometimes frustrated – for example, when the Chicago students, who are just as impassioned, bright and organized as the Parkland kids, see their tragedies and demands ignored by media-makers and politicians alike.

This is a story just a year in. For all of their bluster and effectiveness, the children at the core of Parkland are still young people damaged by an act of horrific violence, savaged by an unforgiving and ideological conservative media, and sometimes sniped at and shunned by their peers. How will that change them? Cullen doesn’t quite get there, perhaps because the students themselves haven’t gotten there yet, and because this is a story about an evolution in progress, not a revolution complete. Cullen’s tale, though, makes you hopeful for what might come next. Optimism about the future: It’s a strange feeling.

“Parkland” is a story touched by trauma, but it is not a story of trauma. It is a story born of violence, but it is not a story of violence. Instead, it is something both braver and more precise: It is the story of a carefully planned rebellion.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story