There are more venues and worthy shows in Maine then we could possibly cover, so this column rarely has reason to venture out of the state. But a blockbuster Ansel Adams exhibit as close to Portland as Bangor – though in the opposite direction – seems worthy of making an exception to visit Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

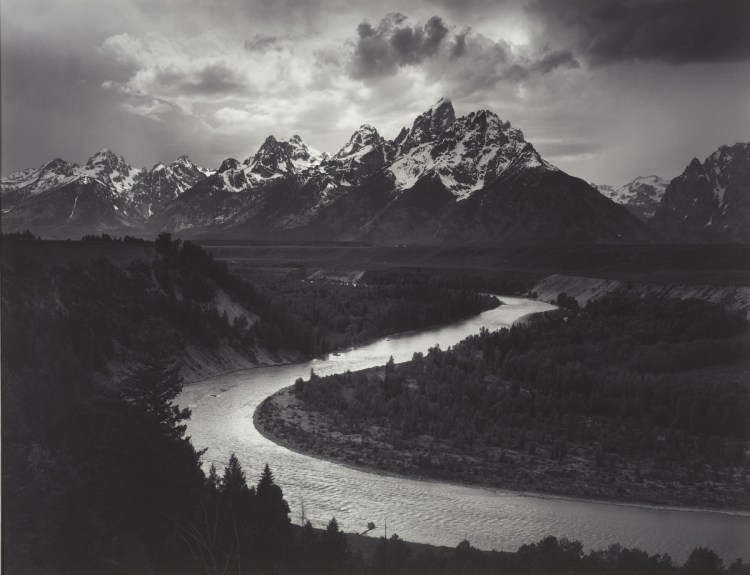

Adams (Feb. 20, 1902-April 22, 1984) was arguably America’s most important photographer with an oversize influence on how we now see the contemporary landscape art. He is best known for black-and-white photographs of the picturesque but wild American landscapes such as Yosemite National Park. He was also an environmentalist who acted in support of the sites associated with the great American landscape.

Adams founded the anti-pictorialist and sharp-focus Group f/64, an association of photographers dedicated to photographic exactitude: full tonal range, sharp focus and clarity. But what matters most about Adams were his technical, aesthetic and ethical echoes, rather than his institutional ripples.

For many years, it has been hip among some circles to dump on Adams for his insistence on technique and formal standards.

The MFA’s “Ansel Adams in Our Time” is a rare show that considers Adams not only by showing a great deal of his own work, but by comparing it to his mentors and models, as well as a select group of artists ostensibly inspired by Adams.

To be sure, Adams was a consummate master of his craft: large-negative black and white high-focus silver gelatin photography. Many contemporary artists, however, aren’t capable of seeing Adams’s political and philosophical content because of his incredible technical standards for aesthetic content in the quickly fading art of silver gelatin photography. This is the critical point: Adams set a teachable standard for the visual tonality of photography, and many contemporary artists are simply allergic to craftsmanship and excellence. The first generations of conceptual art, after all, were philosophically dedicated to the notion that their idea was the “art” and that execution should be perfunctory. So, of course, heading into an era dominated by conceptualists, many lashed out at Adams and saw him – pejoratively – merely as a master of craft.

“Ansel Adams in Our Time” is effective because it shifts the contexts of Adams’s work again and again. Ironically, the 20-or-so contemporary artists included make Adams, by comparison, appear as an artist of unusually robust depth in terms of content. Why? They are virtually all artists with a “schtick” – some specific device to which they adhere for branding purposes. And in their hands, we can better see that what makes Adams so recognizable is not a schtick, but style, aesthetic and technical prowess.

“How the West Is One,” Will Wilson, inkjet print, 2014.

Catherine Opie (b. 1961), for example, was well-known for one schtick (photos of leather-clad lesbians – with the connotations of a political project I very much support) when she was commissioned to do a public project. So she took photos of recognizable places, say, in Yellowstone, and basically hit one button in Photoshop (i.e., Gaussian Blur) to wind up with a set of “artsy” digital prints. Aberlardo Morell (b. 1948) has a more sophisticated schtick, but it’s still all schtick: He constructed a tent-camera camera obscura (a centuries-old tool of using a lens to project the real world onto a flat surface) and shot digital pictures of the projections on the gravelly ground. Binh Danh’s (b. 1977) Daguerrotypes of the same scenes we see throughout the show have no aesthetic, conceptual or formal comment on Adams’s work other than being Daguerrotypes. Out-of-date format? Schtick. (Honestly, silver gelatin printing takes a lot more effort and skill, so this schtick is particularly disappointing – especially in light of seeing the extraordinary comparisons of Adams’s early and later silver gelatin prints.) Trevor Paglan’s (b. 1974) digital prints of colorful clouds with a drone below them – really? If you want interesting work about military optics, check out Dozier Bell’s work over the past 15 years. If you want a decent cloud, look at practically any other photo in the entire show.

“Tent‑Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming,” Abelardo Morell, inkjet print, 2011.

Don’t get me wrong, some of the this-is-my-brand stuff is really good. Will Wilson, a Navajo born in 1969, has a double self-portrait as a cowboy and an Indian: It’s no less poignant than brilliant, and it is brilliant. Chris McCaw’s (b. 1971) reversed black-and-white images of a San Francisco sunrise could have annoyed me (cliche negative imagery equals schtick) but are visually challenging and strong enough to succeed. Matthew Brandt’s (b. 1982) majestic landscapes pulled as silk screens with ketchup and mustard for one and then mole sauce for the other are hilarious because they are visually compelling. Yeah, it’s a schtick, but he ain’t pretending otherwise, and he’s having fun with it – and they are good examples of photography. Stephen Tourlentes’s (b. 1959) series of images of landscapes featuring prisons in remote landscapes at night, again, is on a schticky slope, but this is a series with a worthy (as opposed to look-at-me) point (overcrowded commercial prisons represent human rights violations) and, most importantly, Tourlentes makes gorgeous photographs that reveal a solid understanding of black-and-white grain and Adams-inspired tonality. Laura McPhee (b. 1958) doesn’t have a schtick as much as a subject and a strategy. Her large-scale color diptych of Idaho trees burned from a fire look like they are still burning from within. It is morally compelling but with a magic realism twist that reaches spiritual aspects of the forest contaminated by human actions. Hung near a powerful image by Adams of fire-burned trees, McPhee more than holds up. Message matters.

“Grass and Burned Stump, Sierra Nevada, California,” Ansel Adams, gelatin silver print, 1935.

So here I am championing the work of Carleton Watkins (1829-1916), Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) and Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882) – Adams’ leading inspirations. In addition to Adams – they all appear (appropriately as) extraordinary in “Ansel Adams in Our Time” – and I am dumping on most of the younger artists presented in their wake. Does that make me conservative? Hell no. My complaint about the recent artists in the show is that they are anti-progressive. Adams learned from Watkins, Muybridge and O’Sullivan. He understood their achievements and their excellence. He took every drop possible from them and then brought their paths even farther forward. Sure, that’s Modernism. But it’s also the dialectical Hegelian pulse of Western culture: It’s progressive from its core. Learn from the folks who came before you. Understand their work. And then go further. Carving out your own space and claiming “Mine!” is the opposite of being progressive; grabbing your chunk of copyrightable turf and holding onto it is the very definition of conservative. Branding is fine, but if that’s all you got, then as far as I am concerned: You are morally decrepit in terms of culture. You claim your Hole©, then crawl back into it and stay there. No thanks. Culture is alive, not made up of fixed points on a map.

“Midsummer (Lupine and Fireweed),” Laura McPhee, inkjet print, 2008.

Featuring more than 200 works, “Ansel Adams in Our Time” is a huge show. It strikes a fine balance between Adams, his mentors and a (slightly painful) glance at contemporary photography. It looks, acts and feels like a blockbuster show, and it earns that billing. Adams is a major American artist. Like, say, Claude Monet, Adams’s common culture popularity has made it less appealing for the snobbier types to like his work. But, also like Monet, Adams was – and will continue to be – so much more than his recognizable style. He changed photography in America, and not just with his technique, but with his ideas and aesthetic standards. Monet was a gaming-changing radical. And so was Adams.

“Mount Starr King and Glacier Point, Yosemite, No. 69,” Carleton E. Watkins, mammoth albumen print from wet collodion negative, 1865-66.

If you wanted to read about specific pictures by Adams, or about the incredible side-by-side comparisons between Adams and Muybridge or O’Sullivan or Watkins, well, I am sorry not to have delivered (and, trust me, I would like to have written chapter on chapter about these things – there is so much to say). But Adams’ prints are works you can – and should – see for yourself. Besides, this show will be widely written about, and it’s not like finding these images online is hard. But go to this show. Comparing his early prints to the later prints of the same negatives will make it clear that silver gelatin print is a serious art. You can also see Adams as a photographer far beyond what you might have imagined: city scenes, cemeteries, old men in rocking chairs on a porch, old posters on a city wall, a beautiful Latino child, field workers, the winding snakes of city infrastructure, Native American dancers, a cross in front of a church, and, oh yes, the vast vistas of Yellowstone, Alaska, the Snake River and so much more. There is a reason Adams is so popular for college student posters: Gorgeous matters and smart makes it even better.

“Ansel Adams in Our Time” is a brilliant reminder that Ansel Adams was one of the greatest American artists ever and one of the most influential on our contemporary moment.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story