AUBURN — If you believe the advertising in the latter half of the 19th century, gulping down a bit of Dr. J.F. True’s Elixir offered the best possible treatment for everything from a headache to a lizard living in your stomach.

Regardless of whether it really worked or not, the dark and somewhat alcoholic liquid that was shipped out to druggists across the country under True’s name put Auburn on the map.

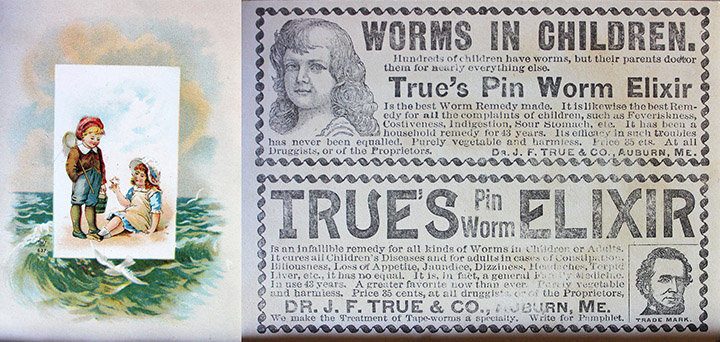

Nearly forgotten today, the Auburn-made mixture was once a staple for many families angling to “Keep Children Well” in an era when the medical profession had yet to find its bearings and sickness was striking down a hefty share of American youngsters.

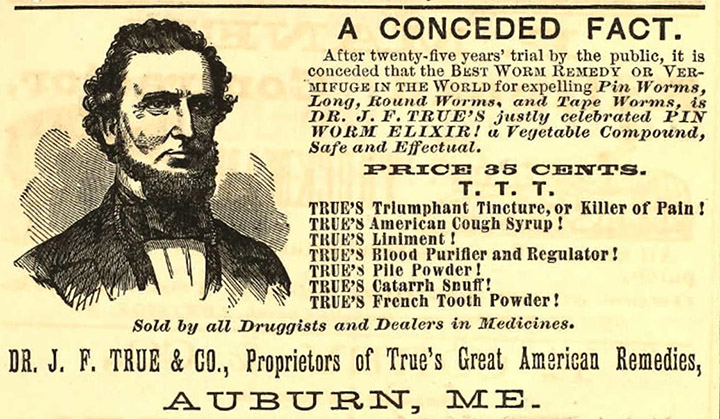

At a time when truth-in-advertising regulations essentially did not exist, True made staggering claims for his brew.

“The best worm remedy made,” one ad claimed. “When True’s Elixir hits the worm, he knows it is useless to struggle and he must surrender.”

He said his concoction would expel tapeworms “head and all in under three hours.”

True insisted his elixir drove out a 70-foot tapeworm from Benjamin Hill of Auburn and a 60-foot one that had tormented “a child of John Ferguson of Lewiston.”

Bad as those sound, True also touted his elixir’s success in releasing a 6-inch-long spotted lizard from the stomach of a Bangor woman and in ridding a boy in Danville of “a living creature 18 inches long and two inches in circumference, a species of snake.”

For many families, True’s Elixir became a cure-all.

When “an anxious mother” wrote to the Talk With the Doctor column in American Motherhood magazine in 1910 about her sickly 4-year-old daughter, she wondered if the girl’s inability to sleep, crying and “very bad odor” might be the result of worms.

“I have given her Dr. True’s Elixir thinking this might help her,” the woman said. The doctor doubted the diagnosis.

In a 1913 case history of pediatric patients, John Lovett Morse mentioned 3-year-old Russell, who was growing weak, acting irritable and picking his nose a lot.

“His mother, suspecting worms, had given him True’s Elixir several times, but never obtained any worms,” Morse wrote.

He said he wouldn’t even take note of the possibility of worms except that the diagnosis was so commonly made by mothers, grandmothers and even doctors who ought to know better.

Joy Swan’s account of a girl’s life in rural Maine more than a century ago, “Aunt Susy’s Boarding House: The Story of A Girl Growing Up In Maine,” showed the importance some placed on True’s medicine.

She said that profits from the fall harvest were used to obtain the essentials, “usually swapped for corn meal, oranges if available, cod liver oil, Dr. True’s Elixir and salt.”

After the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, which forced patent medicine hawkers to tone down their ads, True’s company dropped its most outlandish claims and relied on vague assurances of better health and the long-established habits of customers to continue churning out its famed elixir.

By 1923, True’s company was selling more than 150,000 bottles of the stuff annually. It also offered a wide array of other products, from headache pills to True’s Sore Throat Gargle.

Unlike most of the medicines of its time, the active ingredients of True’s Elixir are not lost to time.

John Phillips Street, a Connecticut state chemist, figured out in 1914 that it contained 8.5 percent alcohol by volume as well as Santonin and Emodin.

Santonin was a widely used drug that paralyzed the heads of parasitic worms, causing them to release their grip on internal organs so they could be passed out of the body. It has been replaced by safer drugs today, but at the time, it was the appropriate treatment for someone with worms.

Emodin is a traditional Chinese herbal laxative made from rhubarb, buckthorn or Japanese knotweed, that invasive species that irks so many Maine gardeners. Emodin is used almost entirely in labs today, replaced by safer alternatives in commercial products.

What else might have been included is unknown.

What is known, though, is that it smelled.

Back in 1972, Colby College historian Ernest C. Marriner mentioned on his radio series “Little Talks on Common Things” that old-timers recalled “the pungent odor of herbs and other concoctions that pervaded the atmosphere” around True’s Auburn laboratory.

THE TRUE STORY

For a widely known figure in his day, there’s surprisingly little available to shed light on the man behind the medicine.

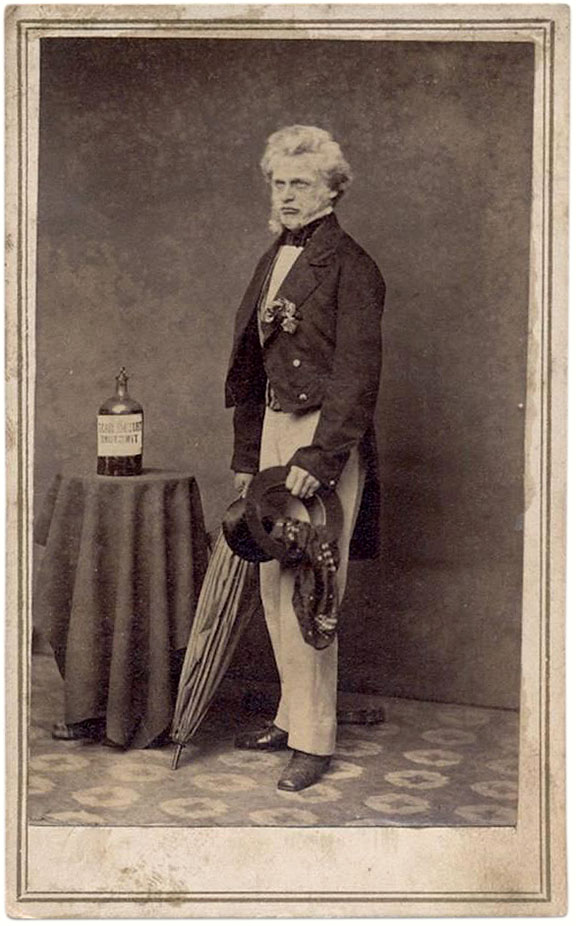

From census records, it appears all but certain that the J.F. True on all those bottles and advertising was John Fogg True, a physician.

Living in Dexter in 1851, True created his famous elixir in his own kitchen “though he did not realize at the time that he compounded a remarkable medicine,” as a 1921 story in the Lewiston Daily Sun put it.

At first, he merely used it himself, then he introduced it to neighbors and, finally, to customers.

One of his first decisions after creating the new medicine was to move away from tiny Dexter to a place just beginning to come into its own, Auburn, which offered ready access to the Androscoggin and Kennebec Railroad. That made shipments to Portland, Boston and beyond far simpler for him.

By 1854, he had moved to Auburn with his wife, who won prizes that year from the Androscoggin County Agricultural Society for her picture frames and woolen hose.

An 1860 business guide listed him as a patent medicine manufacturer on Court Street.

That same year, he took out an ad in the Lewiston Gazette touting his product to local consumers.

“Grand Trunk Canal,” it stated. “As a large amount of freight which should be used for better purposes is being consumed daily by a sponging set of loafers called worms that infest the Alimentary Canal, we would call the attention of those who see and feel the sad effects of those varmints to a safe and effective remedy called Dr. John L. True’s Justly Celebrated Pin Worm Elixir.”

As time passed, more and more New England families opted to keep children safe with regular helpings of True’s Elixir.

By 1877, True had built a laboratory “to keep pace with the ever-increasing demand for his medicines,” according to the 1921 Lewiston Sun story. He expanded it eight years later.

“The product had by this time won a sure name for itself and its worth was recognized in the medical world. It was fast becoming a by-word in the household and proportionately the firm continued growing,” the paper said in a brief history of the company.

True then erected a spacious laboratory in 1891 in the rear of his family home on Drummond Street. He lived in the two-story 1848 colonial that still stands, though his laboratory is long gone.

The Sacred Heart Review in 1897, when it took note of True’s 80th birthday, said the the elixir’s creator had “early adopted the study of natural history and especially botany and became so proficient in these studies that he has long been recognized as an authority.”

Those studies, it said, led to the discovery of the elixir.

It also pointed out that True “has been a consistent taker of his own medicine and attributes to it his wonderful vitality and activity, equal to those of most men of 65.”

He died three years later.

THE MEDICINE THAT MADE AUBURN FAMOUS

Advertising was likely the key to True’s success at a time when snake oil salesmen were hawking patent medicines in any venue where a customer might be found.

It had a long list of newspapers where its ads regularly appeared, placed by the Boston office of one of the country’s biggest marketing firms.

An advertising journal called Printer’s Ink in 1902 mentioned that True’s Elixir “is being advertised with a fine series of pictures in the drug store windows, a well-displayed ad in the newspapers and the distribution of a booklet.”

“All in all, the advertising is so much better than the general run that it is no wonder that the business has grown since 1851 when the product was made in a kitchen to the present pretentious manufactory having six compounding vats, each with a capacity of hundreds of gallons,” the magazine added.

True’s death in 1900 appears to have done little to slow the company’s growth.

After the doctor’s demise, his sons, Edward and James, continued the enterprise for a number of years. In 1907, the Maine Chamber of Commerce said they were doubling the firm’s business each year.

Despite federal regulations, the Auburn company didn’t easily abandon its patent medicine roots.

When a deadly flu epidemic struck in 1918, it headlined an advertisement in a Massachusetts daily “Save Yourself From Influenza.”

It suggested that “if you are run down or out of condition. If sluggish bowels have allowed poisonous impurities to accumulate in your system you are certain to suffer severely with the grippe.”

“Dr. True’s Elixir, the famous household remedy of 67 years’ reputation, will ward off the grippe entirely or make an attack light and easily thrown off,” the ad said. It insisted the vegetable tonic would strengthen digestive powers, relieve constipation and “put the system in good condition.”

By 1921, when the Lewiston paper wrote about the company as it celebrated 70 years in business, it pointed out that “in these days of the multitude of patent medicines, widely advertised products of that nature come and go with regularity, flushing forth in big type for a few months or a year and then disappearing forever.”

But that sort of quick demise was not, it noted, the fate of the “medicine that has made Auburn famous.”

TRUE FATE OF THE FAMED ELIXIR

After the death of True’s sons, the family sold the company in 1947 to Auburn financier George Lane, “who made the business a subsidiary of a larger corporation with a laboratory in Hanover, Mass.,” according to historian Marriner.

Before long, it was owned by George Tobias of Natick, Mass., who manufactured True’s Elixir in the 1950s.

By then, its bottles carried a label calling the elixir “the true family laxative” and warning people that prolonged use “may result in dependence.”

Something else on the label jumps out: Its ingredients had changed.

By 1952, it still contained 8 percent alcohol but its active ingredients were senna leaves and aloin, neither of them present when Connecticut’s chemist analyzed the elixir before World War I.

Senna remains an over-the-counter laxative commonly relied on to treat constipation and also to clear the bowels before such diagnostic tests as colonoscopies.

Aloin is a bitter, yellow-brown compound made from aloe leaves that was also used to treat constipation until the Food and Drug Administration pulled it off the market in 2002 due to safety concerns.

The manufacturer kept churning it out along with some other old patent medicines with renowned names, including Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound.

In any case, the last bottle that carried the Dr. True’s Elixir name landed on a drug store shelf in 1955.

It hasn’t been manufactured since.

Comments are no longer available on this story