GORHAM — The sun is streaming into Tracy Burns’ third-grade class, and the 17 students are still as mice. Up at the whiteboard, she’s introducing them to a new letter: “i” written in cursive.

“OK. We travel uuuup, then bump,” Burns says, writing out the first part of the letter. “Then back down, and bump! And we make a little mouse hole at the bottom – not a tepee!”

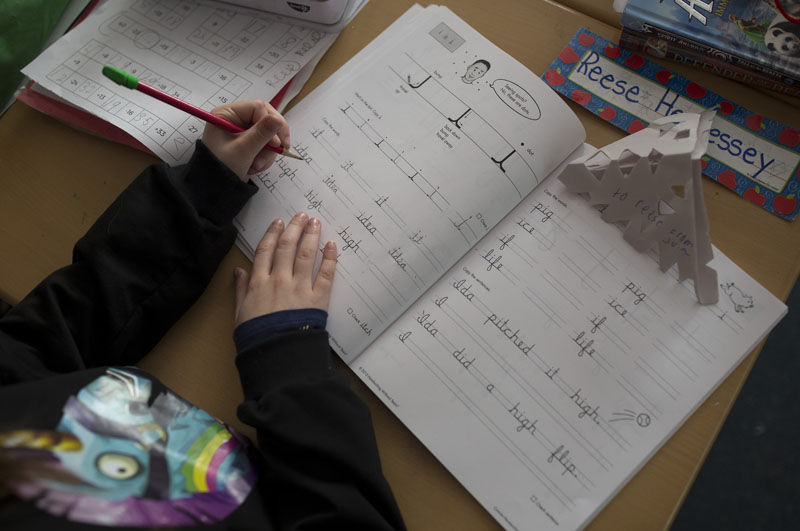

A few moments later, the students all turn to their workbooks, writing out the letter, and words and sentences, all in cursive.

Cursive, it seems, is making a comeback. Once ubiquitous in American schools, cursive has been displaced in recent decades as teachers made room for teaching material for new, tougher standardized tests and modern skills such as keyboarding or coding.

But teachers say they can see the downside – students growing up with hand-held electronic devices have very poor printing skills, let alone the ability to write in cursive.

“I think it’s an art we shouldn’t lose,” said Burns, who has been teaching here at Narragansett Elementary School for seven years. “If we do too much stuff on the computers, their writing deteriorates.”

There are practical considerations as well. Cursive allows students to write faster, get their thoughts down on paper better and improve their retention of information, according to Terri Foster, a Massachusetts-based occupational therapist. She led a seminar for Portland-area teachers last fall for “Handwriting Without Tears,” a company that sells handwriting, cursive and keyboarding products and curriculum.

“At the turn of the millennium, people started saying children will be using keyboards, so we won’t need cursive,” Foster said. “We need to move away from thinking of them as mutually exclusive. Children really need to learn cursive and keyboarding to be successful.”

REQUIRED IN 14 STATES

Students who struggle to write in print can be “saved” by cursive, she said, finding it easier to write.

Most adults ultimately settle on a writing style that is a hybrid of print and cursive – the fastest and most efficient way to write.

Maine does not require cursive instruction, usually introduced in the third grade, but individual teachers and some districts still teach it. Maine’s Catholic schools still require cursive instruction.

Today, cursive is required in 14 states, with Alabama and Louisiana passing laws just last year. In Mississippi classrooms this year, students must be tested on cursive, adding a layer to an earlier state law requiring instruction.

Burns said she’s noticed a shift over the years among her third-graders. Students today don’t have the hand strength that comes from molding Play-Doh, digging around in the dirt or playing with bats and balls for hours. Spellcheck functions online mean they don’t spell as well, or learn from their spelling mistakes.

“I think we need a balance,” she said. Too much time online and “their handwriting is atrocious. They get tired, and their hands hurt.”

Some adults also worry that students who can’t write in cursive will struggle to read it – and that means not being able to read historical documents or a letter from a grandparent.

“It’s disappointing that learning cursive is becoming passé or becoming obsolete because in our line of work it’s not,” said Jamie Rice, library director of the Maine Historical Society. “If there are students who aren’t learning how letters are made, it can be complicated to learn about the past.”

‘WE NEED A SIGNATURE!’

Learning to write in cursive used to be ubiquitous. The fanciest form in the United States – created in the mid-1800s by bookkeeper Platt Rogers Spencer – included multiple whorls and flourishes. That style gave way in the early 1900s to the rounder, simpler Palmer method, a style created and standardized for instruction by Austin Norman Palmer and the schoolroom gold standard for decades.

In the 1970s, the D’Nealian script was introduced, simpler but still with a distinct right-leaning style. Today, the cursive style used by “Handwriting Without Tears” is even simpler, with a distinct upright look compared to the older, slanted styles.

In Burns’ classroom, the students carefully copy the letters in their workbook, rounding the o’s and making sure the t’s are tall and the g’s swing low.

Hayden Rozek, 8, a Narragansett third-grader, said she knows another reason she wants to learn cursive.

“We need a signature!” she says excitedly, her feet tucked up under her on her chair.

Her students love to learn cursive, Burns said: “It makes them feel grown-up.”

“I like that it’s kind of fancy,” said Zach Carlson, noting that the cursive capital “Z” – which he’ll need for his signature – has several whooshing loop-de-loops.

“I think when I grow up, I’ll never write in print again,” he confides. “It kind of looks like scribble, but when you learn how to write it, it all makes sense!”

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

Twitter: noelinmaine

Comments are no longer available on this story