Had Rock Hudson not died of AIDS in 1985, he might be best remembered as the most successful of the postwar male stars who got into the movies solely on their looks. He remained on the screen for decades because of a likability that can’t be learned or manufactured.

Instead, Hudson became the first celebrity to acknowledge that he suffered from the mysterious disease that seemed to target gay men. The potentially career-ending sexual secret he had protected was all but confirmed in the last months of his life.

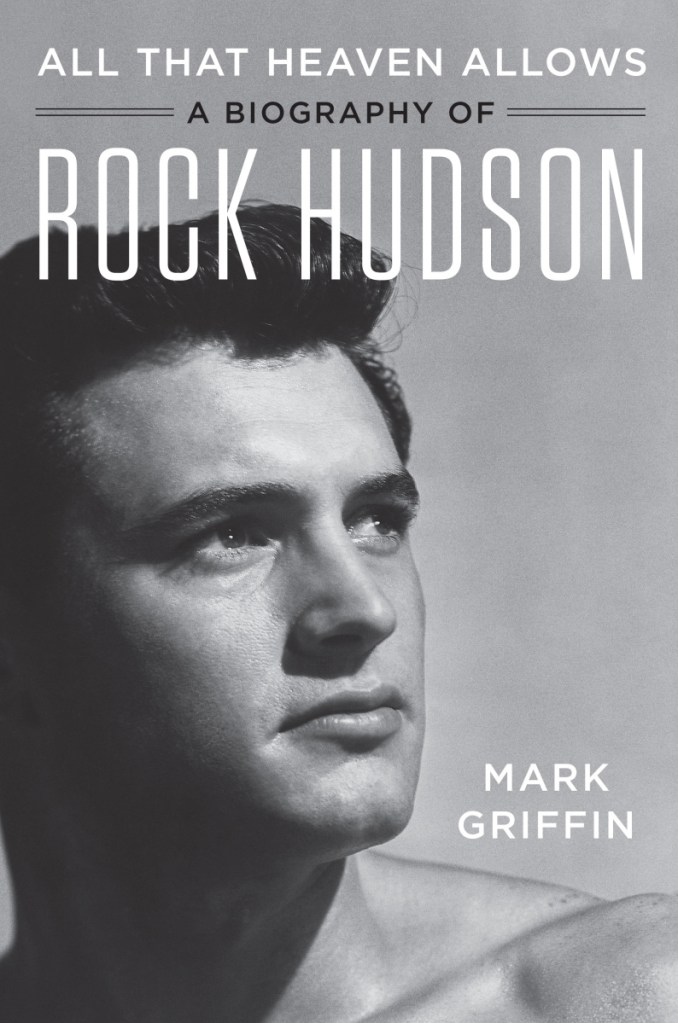

Mark Griffin’s perceptive and sympathetic biography “All That Heaven Allows” gives Hudson, both the movie star and the man, the kind of reassessment only time can allow. He improved as an actor yet never lost the fear that moviegoers would discover that their ideal leading man was only playing a role.

While he needed time and experience to hone his craft, pretending for the cameras came easy to handsome, Illinois-born Roy Fitzgerald. Escaping reality at the Winnetka movie theater was a must for the boy with an overprotective and domineering mother, a father who walked out on the family, and a stepfather who beat him. Childhood friends remembered Roy for many of the same qualities that made him a favorite with fellow actors and film crews: diligence, generosity, easygoing charm and fun-loving spirit.

Living a closeted life and trying to make it as an actor only added to his insecurities. With his new name, Hudson appeared in more than two dozen films under contract to Universal between 1948 and 1954. Eager to learn, he blossomed under the direction of Douglas Sirk, whose romantic tearjerkers “Magnificent Obsession” (1954) and “All That Heaven Allows” (1955) turned Hudson into a heartthrob at 30.

With the hugely successful epic “Giant” (1956), Hudson was an Oscar-nominated actor and soon Hollywood’s most popular star. Routine dramas followed until 1959’s “Pillow Talk” with Doris Day revealed Hudson’s knack for light comedy. He remained an audience favorite for several more years despite undistinguished movies. Imagine what might have been had Universal followed through on its original plan to cast Hudson as lawyer Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

All the while Hudson lived and loved on the down-low. A sham marriage around the time of “Giant” quelled the gossip for a time. Publicly, he played along with the fan magazine image of the happy if lonely bachelor trying to find the right woman when he was actually trying to find the right man. Promiscuity as well as meaningful relationships marked his private life. Had Hudson been a straight star, he may have been married several times and envied as a ladies’ man.

Griffin suggests that Hudson’s better performances – the paranoia classic “Seconds” (1966) being one example – came with roles in which he could identify with a character’s internal turmoil. Wisely, the writer explores Hudson’s films and TV shows without trying to make them more than what they were – generally average entertainments punctuated by occasional hits and many, many misses. (TV’s “McMillan & Wife” resuscitated his flagging career in the 1970s.) Like most other aging stars, Hudson struggled to find good roles as the wrinkles appeared. Alcohol and cigarettes took a toll on his health long before the AIDS diagnosis.

Given his generation’s intense homophobia and the 1950s communist witch hunt that ruined so many careers, it’s understandable that Hudson didn’t want to risk everything as a gay-rights pioneer. But he was indiscrete enough that his secret was widely known or assumed in Hollywood and elsewhere (FBI and police files suggest as much).

Griffin’s interviews and correspondence with many of Hudson’s co-stars – among them Doris Day and Carol Burnett – and many of his lovers show how protective they were of their warm, loyal friend. Had he lived into the next century, the abandoned and abused boy from Winnetka might have discovered a public ready to root for him to be who he really was.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story