Maine winters are notoriously cold. The first snow can fall as early as late October and some years, we’re lucky to see it gone by early May. The days are short and the nights are cold. Just imagine how much colder it must have seemed in the eighteenth century when our town was first settled.

New Marblehead, as Windham was called at the time, was considered wilderness. Settlers such as Thomas Chute and William Mayberry would have lived very rustically in log homes where the only source of heat was a large fireplace also used to their cook meals.

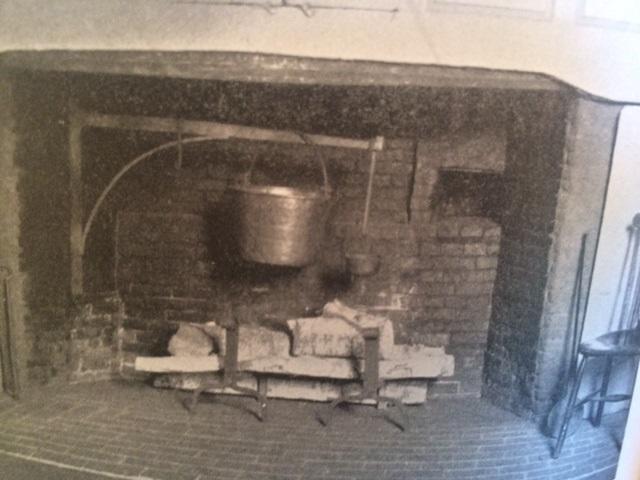

If they were lucky, the home would have had a beehive oven like the one that still graces the Parson Smith House today. Colonial cooks would rise before dawn to begin the baking process on their weekly “baking day.” On that day, the family meal would be a simple one consisting of stew or cold meats and pies. The cook would sweep the oven floor clean with a long-handled broom and then start a fire using pinecones and twigs for kindling. When the fire took hold, larger pieces of wood would be added and allowed to turn to ashes. This process took 3 to 4 hours and then baking would begin. Dense breads would be baked in the middle of the oven and light breads and cakes would be placed upfront. It was a hard day for the lady of the house, but at least it kept her warm on stormy winter days.

Besides doing the cooking, Colonial women would have been busy spinning; weaving; sewing; making soap, candles and baskets; cleaning; and tending animals used for food such as chickens and geese. In addition, the women would have cared for the children and acted as family physician – sickness was no stranger in the winter months.

The men of the house would have been out cutting and gathering wood for the fire and hunting for food for winter meals. Since most of these rugged pioneers were jacks-of-all-trades, they may have also spent winter days crafting furniture for their homesteads. New England farmhouses were scantily furnished and people were not that concerned with comfort, but a nice table and chairs and a warm bed were welcome in any household. The gentlemen also handled the family finances and as some were skilled tradesmen, they could add some income by selling the goods of their trades.

Occasionally, a special event would occur in the wintertime. These happy occasions, such as births or weddings, were a welcome call for festivity. Local townspeople may have been invited to the Old Tavern in the Center where innkeeper William Hanson would have offered fine spirits and pub fare to the family’s guests. It was a wonderful time to socialize, discuss politics and religion and possibly have a dance to the music of a local fiddler, much to the dismay of the more pious members of the community.

It was not an easy life for the founding families of our town. They lived through long winters that sometimes left them feeling isolated. There were gatherings at the taverns and at the fort, but life on the frontier was mostly spent on the farm with one’s own family. There were many a winter night where these families sat huddled by the fire making brooms, shelling nuts and telling tales. It made them a close-knit unit. And though outside it was cold, the comfort of their love kept them feeling warm.

Windham resident Haley Pal is an active member of the Windham Historical Society.

The fireplace in the Parson Smith House has a beehive oven, they type often used by colonial women. This photo comes from “A History of Windham Maine” by Frederick H. Dole.

Comments are no longer available on this story