WASHINGTON — President Trump tested the limits of his presidential authority and political muscle as he threatened Tuesday to cut off all federal subsidies to General Motors because of its planned massive cutbacks in the U.S.

Trump unloaded on Twitter a day after GM announced it would close five plants and slash 14,000 jobs in North America. Many of the job cuts would affect the Midwest, the politically crucial region where the president promised a manufacturing rebirth. It was the latest example of the president’s willingness to attempt to meddle in the affairs of private companies and to threaten the use of government power to try to force their business decisions.

“Very disappointed with General Motors and their CEO, Mary Barra, for closing plants in Ohio, Michigan and Maryland” while sparing plants in Mexico & China, Trump tweeted, adding: “The U.S. saved General Motors, and this is the THANKS we get!”

Very disappointed with General Motors and their CEO, Mary Barra, for closing plants in Ohio, Michigan and Maryland. Nothing being closed in Mexico & China. The U.S. saved General Motors, and this is the THANKS we get! We are now looking at cutting all @GM subsidies, including….

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 27, 2018

Trump’s tweets came a short time after National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow said the White House’s reaction to the automaker’s announcement was “a tremendous amount of disappointment, maybe even spilling over into anger.” Kudlow, who met with Barra on Monday, said Trump felt betrayed by GM.

“Look, we made this deal, we’ve worked with you along the way, we’ve done other things with mileage standards, for example, and other related regulations,” Kudlow said, referring to the recently negotiated U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement. “We’ve done this to help you and I think his disappointment is, it seems like they kind of turned their back on him.”

The White House rebuke appears to fly in the face of long-held Republican opposition to picking winners and losers in the marketplace. A day earlier, Trump issued a vague threat to GM warning it to preserve a key plant in the presidential bellwether state of Ohio, where the company has marked its Lordstown plant for closure.

“That’s Ohio, and you better get back in there soon,” he said.

It’s not clear precisely what action against GM might be taken, or when, and there are questions about whether the president has the authority to act without congressional approval.

Buyers of electric vehicles made by GM and other automakers get federal tax credits of up to $7,500, helping to reduce the price as an incentive to get more of the zero-emissions vehicles on the road. But GM is on the cusp of reaching its subsidy limit.

White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said she did not have any additional information on the president’s threat.

Trump has long promised to return manufacturing jobs to the United States and particularly the Midwest. At a rally near GM’s Lordstown plant last summer, Trump told people not to sell their homes because the jobs are “all coming back.”

In a statement Tuesday afternoon, GM tried to appease the Trump administration while at the same time justifying the decisions it announced Monday. “We appreciate the actions this administration has taken on behalf of industry to improve the overall competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing,” the statement said.

Many of the workers who will lose jobs if the plants close could transfer to another GM factory where production is being increased, spokesman Patrick Morrissey said. For instance, GM plans to add hundreds of workers at its pickup truck assembly plant in Flint, Michigan, Morrissey said. Workers also will be added at an SUV factory in Arlington, Texas.

But those expansions aren’t enough to accommodate all of the roughly 3,300 U.S. factory workers who could lose their jobs.

GM said it has invested more than $22 billion in U.S. operations since 2009, when it exited bankruptcy protection.

Trump has made direct negotiation with business leaders a centerpiece of his administration, including talks with defense contractor CEOs on bringing down prices on new systems, including the upcoming replacement to the aircraft that serves as Air Force One. He has never been shy about voicing his frustration with their decisions.

But Trump’s deal-making image is far from flawless. Three weeks after his election, Trump traveled to Indianapolis to announce a tax-incentive agreement partially reversing the closure of a Carrier factory, which was set to close, cutting about 1,400 production jobs.

Trump frequently criticized the closure plans during the 2016 campaign, and promised to prevent similar occurrences in the future. Under that deal, Carrier pledged to keep nearly 1,100 jobs in Indianapolis, including some 800 furnace production jobs it planned to cut with outsourcing. But about 550 jobs were still eliminated at the plant.

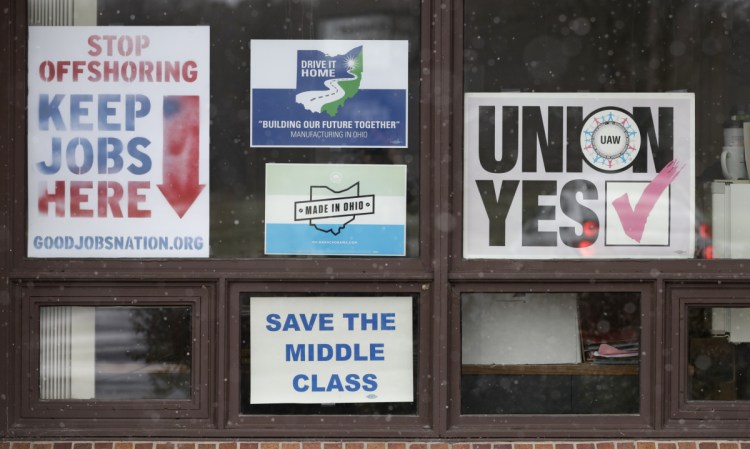

GM’s attempt to close the factories still has to be negotiated with the United Auto Workers union, which has promised to fight them legally and in collective bargaining.

The factory announcements likely represented GM’s opening bid in contract talks with the union that start next year, said Kristen Dziczek, vice president of labor and industry with the Center for Automotive Research, an industry think tank in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The factories slated for closure could get new products in exchange for items the company wants from the union, she said.

Keeping open a plant slated for closure is not without precedent for GM. In 2009, for instance, GM announced that it intended to close a huge assembly plant in Orion Township, Michigan, north of Detroit. But it later negotiated concessions from the union and reopened the plant to build the Chevrolet Sonic subcompact car. The factory is still in operation and now builds the Sonic and the Bolt electric car.

The reductions could amount to as much as 8 percent of GM’s global workforce of 180,000 employees.

The restructuring reflects changing North American auto markets as manufacturers continue to shift away from cars toward SUVs and trucks. In October, almost 65 percent of new vehicles sold in the U.S. were trucks or SUVs. That figure was about 50 percent cars just five years ago.

Jerry Dias, president of the Canadian trade union UNIFOR, said Tuesday that GM’s CEO had insulted the president of the United States and prime minister of Canada.

“If you are going to have a company that’s going to show us their middle finger then I think our government should show them our middle finger as well,” Dias said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story