BERWICK — It was 1894 and Eleanor Pray found herself more than 6,000 miles from home, living on the shores of far eastern Russia and writing to her family in Maine about a life she never imagined she’d be living.

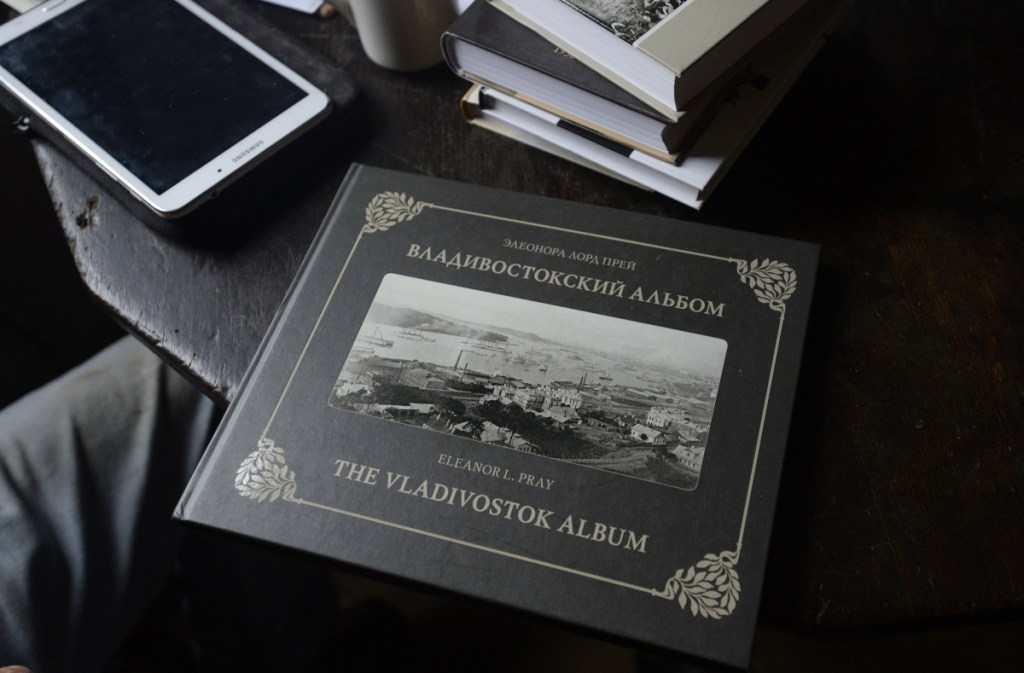

The thousands of letters she sent home to Berwick paint a picture of a farm girl from small-town Maine navigating her new bourgeois lifestyle and provide an astonishing record of life in Vladivostok from the time of Czar Alexander III to the early years of Stalin’s rule. And Pray’s letters and photographs, uncovered decades after her death by her granddaughter and now housed in the Library of Congress, have connected a small town on the Maine-New Hampshire border to a bustling Russian port city, where a bronze statue of Pray clutching a letter to her chest stands near her home of three decades.

The existence of Eleanor Pray – let alone her legacy of words and images – is not widely known in Berwick, but in Vladivostok she is celebrated for providing an opportunity for the city to rediscover a piece of its history that had been lost to war and the Russian Revolution.

“To have largely lost a history of a place, then to rediscover some of it in letters that were unearthed halfway across the world, that has been the source of profound and ongoing fascination by people in Vladivostok,” said Nina Maurer, the consulting curator at the Olde Berwick Historical Society. “People have found in this person a piece of their heritage that they thought was lost.”

The Arseniev State Museum in Vladivostok a decade ago opened an exhibit about the American woman that remains popular with visitors, and curators now hope to open a larger exhibit in the home where Pray once lived.

A group of curators from the Vladivostok museum visited Berwick last month to study Pray’s early life and the society she lived in before she moved to Russia as a young newlywed. With them was Birgitta Ingemanson, a retired college professor from Washington state who has compiled Pray’s letters into multiple books and is researching another about the “folks at home” in Berwick who read and saved the letters Pray sent them.

“To me, it’s a miracle all of this has taken place,” said Paul Boisvert, a Berwick resident and co-owner of the house where Pray grew up. “People in our town don’t know much about Eleanor Lord Pray and they need to.”

Paul and Pat Boisvert in front of the childhood home of Eleanor Lord Pray, who moved to Vladivostok, Russia, and wrote home thousands of letters documenting her time in the Russian Far East at the turn of the last century. Thursday, November 1, 2018. Staff photo by Shawn Patrick Ouellette

A NEW LIFE IN EAST SIBERIA

In the 1970s, Pray’s granddaughter, Patricia Dunn Silver, began going through her grandmother’s letters after her mother, Dorothy, asked if she’d like to see them before they were thrown out. The letters were jumbled together, but Silver pieced them into chronological order, matching pages from letters by the handwriting and color or design of the stationery.

Silver also began to uncover the previously untold tale of her grandmother.

Roxanna Eleanor Lord was born in 1868 and grew up in Berwick in a house she called Elm Wold, a tidy cape just uphill from the river separating the small farming town from neighboring Somersworth, New Hampshire.

As a young woman, she worked for seven years at a mill in Somersworth, crossing the river each day on a footbridge near her house. Eleanor Lord, nicknamed Aunt Roxy by family members, was 26 when she married Frederick “Ted” Pray and moved with him to Russia to work in the “American Store” owned by his sister and brother-in-law, Charles and Sarah Smith.

In the spring of 1894, the Smiths and Prays went to East Siberia together, traveling first by train across the United States to San Francisco, then by schooner to Japan and on to Vladivostok. In Russia, they were members of the well-to-do middle class.

Vladivostok is a port city on the Golden Horn Bay, not far from Russia’s borders with North Korea and China. The city, with a current population just over 600,000, is the homeport of the Russian Pacific Fleet and the country’s largest port on the Pacific Ocean. When Pray moved there, Vladivostok was still a remote outpost, some 7,000 miles east of Moscow and 16 hours ahead of Washington, D.C.

“It’s still astonishing for me to imagine a woman in the 1890s emigrating to a city on the far reaches of the Pacific. It was a frontier,” said Maurer, the Olde Berwick Historical Society curator. “Eleanor Pray discovered that she was in a privileged social situation in Vladivostok that she didn’t enjoy here.”

CHRONICLING LIFE, POLITICAL TURMOIL

From the first day of her journey, Pray wrote long letters to her family and friends in New England. Some letters were 40 or 50 pages long, describing in detail the meals she ate, the visits she had with new friends who had moved from all over the world to live in Vladivostok and, in time, the political turmoil that drastically altered the city she grew to love.

Eleanor Lord Pray, in black evening dress, 1898. The Maine native moved to Vladivostok, Russia, with her husband in 1894, when she was 26.

“A farm girl from Maine, Roxy Pray lived through great events and had the wherewithal to record them,” Silver wrote in a biographical sketch included in Ingemanson’s book of Pray’s letters. “In Vladivostok, she learned to speak several languages, read voluminously, and led a vibrant, cosmopolitan life very different from that of her provincial origins. She met generals, admirals, royalty and political leaders, and she danced to her heart’s content aboard the warships in the harbor. She also saw the vast destruction of people and property during the political turmoil of the time, and lost everything that she held dear in Vladivostok except her memories and her pride.”

Pray’s early letters home to Maine described navigating life in a new country. She wrote, too, of the beauty of the hills rising around Vladivostok, the way a ship “waltzed” across the nearly frozen Golden Horn Bay and of the simple joy of collecting mushrooms in an open field.

“Beyond Paris, Vladivostok is probably the most fascinating city on Earth at the moment. … We are so lucky to witness so many interesting things happening around us here and now in Vladivostok,” Pray wrote.

But by 1904, the Russo-Japanese War was in full swing and Pray’s letters home began to include descriptions of how life in Vladivostok was changing. In April of that year, Pray received an inquiry from the State Department in Washington about her safety.

“I was feeling particularly blue when it came and it just warmed my heart for I felt that Uncle Sam was watching over his own,” she wrote to her family.

Pray had once “long(ed) to live in war times,” she wrote in a 1905 letter home, but later turned against war because of its inordinate human cost.

At the start of World War I, Pray stood on a train platform to wave goodbye to German friends headed into exile. During political upheaval that began in 1914 and continued into the 1920s, many foreigners living in Vladivostok left the city to return home. Those who stayed, including the Prays, were uprooted from the lifestyle they had enjoyed.

Frederick Pray went to work for the U.S. Consulate in Vladivostok and, in 1918, closed the American Store. Soon thereafter, Eleanor Pray began work as a volunteer and treasurer with the Vladivostok chapter of the American Red Cross. After the death of her husband in 1923, Pray was left “a bourgeois lady trying to find her way in a socialist society,” Ingemanson said. Pray took tenants in her home, cooked frugal meals and went to work as a bookkeeper to support herself.

When the firm where she worked closed in 1930, Pray had no choice but to leave Vladivostok for Shanghai, China, where her daughter attended school and her sister-in-law Sarah worked as a dorm mother.

In one of her last letters from Vladivostok, Pray wrote about her farewell dinner, describing the bowls of snapdragons and white dahlias on the table, the cold salmon served for dinner and the lump in her throat at the idea of leaving it all behind.

“Here I am, sailing on and on, every turn of the screw taking me farther from the loved home of 36 years,” Pray wrote from aboard the SS Gleniffer as she left Vladivostok.

INTERNED BY JAPANESE IN WWII

Pray stayed in Asia for years after leaving Vladivostok. After the attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II, her family was interned in a Japanese prison camp. They were liberated in late 1943 and returned to the United States in an exchange of American and Japanese prisoners of war. Pray was ordered to take with her no personal documents, but she smuggled out a cache of letters in her corset.

Pray died in 1954 in Washington, D.C., at age 85. Her body was returned to New Hampshire to be buried alongside her husband and the Smiths in Somersworth.

Though she did not return to New England to live in her later years, Pray never lost sight of her roots or her love for Maine.

“Eleanor never relinquished her Yankee heritage,” said Pat Boisvert, one of the co-owners of the Lord house in Berwick. “She never lost her American spirit.”

In October, the Russian museum curators spent more than a week in the Berwick area taking a course with Ingemanson to learn more about Pray’s roots and Maine in the late 1800s. They listened to the Baptist hymns Pray enjoyed, visited places she described in letters, and studied Victorian traditions and American culture. They visited the house near the Salmon Falls River where Pray spent her early years and met with the locals who are now discovering a piece of their own town’s history through visits with Russians and the 3,200 letters Pray sent home.

The Arseniev State Museum’s exhibit about Pray has continued to be popular with visitors, who also use books of Pray’s letters and photos to explore the city. The house where Pray lived in Vladivostok is now an apartment building, but the museum wants to transform it into an exhibit that showcases life in the port city in the early 1900s.

“It’s human nature to find out what life was like 100 years ago,” said Anzhelika Petrick of the Arseniev State Museum. “(Pray) was just a common person and people really want to know how life was in the city.”

The Russian interest in Pray’s life is a source of ongoing fascination for Paul and Pat Boisvert, history buffs who bought the Lord house with friends Frank and Linda Underwood when it was at risk of being sold to a developer. At the time, they had never heard of Pray or her journey abroad, only becoming aware of Pray after receiving a letter from Ingemanson mailed to the Lord house seeking more information about the family that had lived there for generations.

Over the past three years, the Boisverts have delved into Pray’s history, even sending a trunk with Russian shipping labels they found in her childhood home to the Vladivostok museum.

“We’re trying to build bridges between us and the Russians,” Paul Boisvert said. “When something like this happens, especially at times like this, it’s nice to have a connection.”

Gillian Graham can be contacted at 791-6315 or at:

ggraham@pressherald.com

Twitter: grahamgillian

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story