Badly hung over, the detective rises from a foldout couch in his office. He turns off the TV that has been on all night, dunks his head in ice water, shuffles into the kitchen and prepares a fresh coffee filter, only to realize he is out of grounds.

He opens his wastebasket. Spies yesterday’s filter. Hesitates . . . and fishes it out. He gulps from his mug with an expression of revulsion and resignation, imparting everything the viewer needs to know about his life. The rotten coffee is the least of his problems.

That opening scene, from the 1966 mystery film “Harper,” starring Paul Newman, is widely considered a masterpiece of screenwriting, revealing depths of character without a single word.

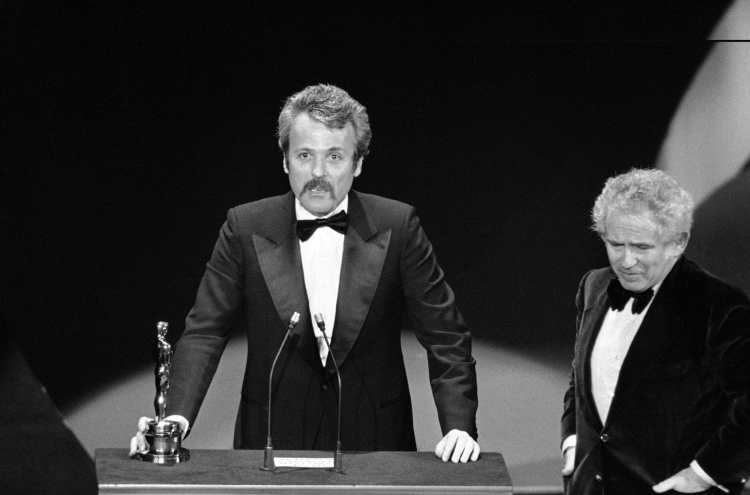

It was the work of novice screenwriter William Goldman, who went on to become a towering craftsman of the movies — winning Academy Awards for the convention-flouting western “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969) and the Watergate thriller “All the President’s Men” (1976) and adapting his fantasy-sendup novel “The Princess Bride” into a generational touchstone in 1987. He died Nov. 16 at 87 at his home in Manhattan of complications from colon cancer and pneumonia, his daughter Jenny Goldman said.

In a career spanning more than five decades, Mr. Goldman regarded himself as a novelist who just happened to write motion pictures. “In terms of authority,” he wrote in “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” his 1983 memoir and acid critique of show business, “screenwriters rank somewhere between the man who guards the studio gate and the man who runs the studio (this week).”

But his film legacy vastly overshadowed his best-selling and genre-crossing books. He became a phenomenal critical and commercial success in Hollywood, not least for his talent for indelible cinematic phrasemaking.

From “Butch Cassidy”: “Rules??! In a knife fight?”

From “All the President’s Men”: “Follow the money.”

From “The Princess Bride”: “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

From “Marathon Man,” his Nazi-conspiracy novel turned film, which contains the most terrifying dental sequence of all time: “Is it safe?”

With a rare exception of talents such as Billy Wilder, screenwriters had long tended toward obscurity. Mr. Goldman became one of the first authors to change that tradition when “Butch Cassidy” fetched what even he considered an outlandish $400,000 in a studio bidding war. It made him an instant celebrity, lionized and vilified.

“It got in all the papers, because nobody at this time knew anything about screenwriters — because all they knew is that actors made up all the lines and directors had all the visual concepts,” he told the Writers Guild Foundation. “And the idea of this obscene amount of money going to this [guy] who lives in New York who wrote a western drove them nuts. It was the most vicious stuff, and, when the movie opened, the reviews were pissy.”

The tale of inept bank robbers was a virtuosic takedown of the mythology surrounding the American West. Newman played the fast-talking outlaw Butch; Robert Redford, then a relative unknown, was cast as his sardonic partner in crime, Sundance.

Their tough-guy attitudes are played for laughs in a memorable cliff dive into a raging river. They need to make the leap to evade a posse, but Sundance confesses he can’t swim. “Are you crazy?” Butch chortles. “The fall will probably kill ya.”

Critics were slow to embrace the film — Pauline Kael’s review in the New Yorker ran with the headline “The Bottom of the Pit” — but audiences responded to its comically absurdist, anti-establishment tone. An interlude featuring Butch and a female companion riding a bicycle to the tune of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” became one of the most memorable sequences in 1960s cinema. The film cost $6.5 million to produce and generated more than $40 million, and it made Redford a breakout sensation.

Mr. Goldman collaborated with Redford on several more films, most notably but most unhappily “All the President’s Men,” based on the book by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein about the Watergate break-in and coverup that led to President Richard M. Nixon’s resignation.

Redford had purchased the rights to the book and hired Mr. Goldman to write the movie version. “It seemed, at best, a dubious project,” Mr. Goldman wrote in “Adventures in the Screen Trade.” “Politics were anathema at the box office, the material was talky, there was no action.”

Mr. Goldman looked upon the Watergate saga, with its inept conspirators, as something of a “comic opera.” He opened with the break-in by Nixon operatives at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, presenting the burglars as bumblers with the wrong set of keys.

Redford, who like the reporters regarded the affair as a grievous subversion of democracy, reportedly objected to the shaggy-dog approach, reminiscent of “Butch Cassidy.”

Many hands began operating on the script — a source of discontent for Mr. Goldman. He took credit for the movie’s unorthodox finale, which showed Woodward and Bernstein making an embarrassing mistake. Mr. Goldman believed that audiences, who would watch the film for the first time two years after Nixon resigned, would understand that the reporters, dogged but human, had been vindicated.

Mr. Goldman’s screenwriting career later soared under director Rob Reiner with “The Princess Bride” — a fractured fairy tale that winks at cliches of romance and swashbuckling adventure — and then “Misery” (1990), based on Stephen King’s novel about a popular writer held hostage and brutalized by a sociopathic fan. (Mr. Goldman helped write the 2015 Broadway play version starring Bruce Willis and Laurie Metcalf.)

Among other films, Mr. Goldman worked on the tongue-in-cheek western “Maverick” (1994); and “Absolute Power” (1997), adapted from David Baldacci’s best-selling suspense novel; and two further King adaptations, “Hearts in Atlantis” (2001) and “Dreamcatcher” (2003). For years, Mr. Goldman was one of the best-paid script doctors in Hollywood, reportedly making $1 million for four weeks’ work.

Mr. Goldman, who learned his trade from a screenwriting guidebook he bought in 1964 at an all-night bookstore in Times Square, abhorred film schools and auteur theory. In profanity-laced interviews, he repeated his mantras: “Screenplays are structure,” “stories are everything.”

“It’s not like writing a book,” he said to the publication Creative Screenwriting in 2015. “It’s not like a play. You’re writing for camera and audiences. One of the things which I tell young people is, when you’re starting up, go to see a movie all day long.”

“By the time the 8:00 show comes,” he continued, “you’ll hate the movie so much you won’t pay much attention to it. But you’ll pay attention to the audience. The great thing about audiences is, I believe they react exactly the same around the world at the same places in movies. They laugh, and they scream, and they’re bored. And when they’re bored it’s the writer’s fault.”

‘Nobody knows anything’

William Weil Goldman was born in Chicago on Aug. 12, 1931, and grew up in the suburb of Highland Park. His upbringing was tense, with a mother he described as hectoring and an alcoholic businessman father who committed suicide by overdosing on pills when Mr. Goldman was 15.

Movies were his escape, and his favorite was the 1939 adventure film “Gunga Din,” which featured a scene that inspired the cliff-leaping episode in “Butch Cassidy.” He entered Oberlin College in Ohio aspiring to write short stories but had ludicrously bad luck getting any published, even while serving as an editor of a campus literary magazine.

“I would anonymously submit my short stories,” he told the London Guardian. “When the other editors — two brilliant girls — would read them, they would say, ‘We can’t possibly publish this [rubbish].’ And I would agree.”

He graduated in 1952, spent two years in the Army, then received a master’s degree in English from Columbia University in 1956. While working toward a doctorate, he wrote his first novel in a three-week catharsis of pent-up fear that he would wind up as a high school English teacher in Duluth, Minn. — the only job offer he had waiting.

The resulting book, “The Temple of Gold” (1957), a coming-of-age story, impressed a prestigious publisher, Alfred A. Knopf. Other books followed at a furious clip, among them “Boys and Girls Together,” a 1964 bestseller about a group of struggling young adults in New York, and his Boston Strangler-like thriller “No Way to Treat a Lady,” published the same year and turned into a film in 1968 starring Rod Steiger as a psychopathic killer with a penchant for disguise.

Mr. Goldman adapted for film several novels, including Ira Levin’s suburban horror story “The Stepford Wives” (1975) and Cornelius Ryan’s World War II book “A Bridge Too Far” (1977). His screenplay for his 1974 novel “Marathon Man,” about a graduate student who stumbles on a nest of modern-day Nazis, became a hit 1976 film with Laurence Olivier as a dentist who drills into teeth as a method of torture. He also wrote the original script of “The Great Waldo Pepper” (1975), with Redford as a barnstorming pilot.

Mr. Goldman’s later books included the Hollywood casting-couch story “Tinsel” (1979), the Cold War science-fiction thriller “Control” (1982), and “Hype and Glory” (1990), a droll reflection on his service as a judge at the Cannes Film Festival and the Miss America Pageant.

His 30-year marriage to photographer Ilene Jones ended in divorce in 1991. In addition to his daughter, of Philadelphia, survivors include his domestic partner of 19 years, Susan Burden of Manhattan; and a grandson.

Another daughter from his marriage, Susanna Goldman, died in 2015. His brother, James Goldman, who won an Oscar for his screen adaptation of his play “The Lion in Winter” and wrote the book to Stephen Sondheim’s musical “Follies,” died in 1998.

In “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” with its gossipy behind-the-scenes look at the caprice of art and commerce, Mr. Goldman coined an enduring phrase in the Hollywood lexicon: “Nobody knows anything.” After decades in the business, he had come to see success and failure as a matter of chance.

He had his share of flops, such as “The Ghost and the Darkness,” a 1996 thriller about the hunt for two lions who kill railway workers in Africa. It was a taut story, starring Michael Douglas and Val Kilmer, and got strong reviews but played to empty theaters.

“If you can believe in the existence of evil, you can understand that story,” he told the Guardian in 2009. “Nobody wanted the lions to be that successful. We live in a Disney world. Maybe we miscast the lions.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story