RUMFORD — Interest in the midterm elections seems extraordinarily high, with Democrats running largely as a check on President Trump’s power while Republicans tout economic successes and stoke fears about immigration.

In states like Maine, there is a competitive race for governor, and dozens of House and Senate seats are up for grabs as well, not to mention a referendum and a series of bond questions.

But in many places, prospective voters are paying little attention to any of it. Tens of thousands in Maine, and millions nationwide, will not vote, especially in a midterm.

“I just don’t follow politics,” said Tom Currivan, 27, who works at the public library in Rumford, a mill town of about 5,500 residents in Oxford County. “I feel like whatever happens isn’t going to affect me either way, so I don’t bother voting.”

Among Maine towns with at least 5,000 residents – excluding college towns, which always have lower-than-average turnout – Rumford has seen the lowest voter turnout in each of the last two statewide elections, 54 percent in 2014 and 62 percent in 2016. Conversations with more than two dozen residents in late October revealed that there are many who have never voted or have checked out in recent years. The reasons for their disinterest varied but many had similar answers: My vote doesn’t matter. I don’t like any of the candidates. I don’t know enough about the issues. Things are too negative.

Dawson Walton, a personal trainer at the Greater Rumford Community Center, said he doesn’t plan to vote on Tuesday either.

“I feel like I’d rather be apolitical at the moment,” he said. “The machine is going to do what it’s going to do.”

Compared to other states, Maine is quite electorally involved. In the last midterm, Maine had the highest turnout of any state, about 58.5 percent of registered voters. In 2016, the state saw 73 percent turnout, trailing only Minnesota.

Still, there are pockets of disillusion, alienation and, sometimes, apathy.

“That surprises me because this seems like a place where people are engaged,” Town Clerk Beth Bellegarde said.

Mark Brewer, a political scientist at the University of Maine, said he thinks the current political climate is having an impact.

“It can work differently among different types of people,” he said. “People who tend to pay at least a minimal amount of attention, they might be more likely to vote. But if you’re a more tenuous participant, if you don’t always vote, you might be more likely to throw up your hands or tune out. There is a difference between apathy and alienation. Apathy is bad, but alienation is far worse.”

Lauren Bridges remembers being so excited to turn 18 so she could vote. She’s 33 now and those feelings are long gone.

“It just seems like politics is much more aggressive and unfair,” she said. “It’s about money, not support from people like me.”

MAGNIFIED SENSE OF ISOLATION

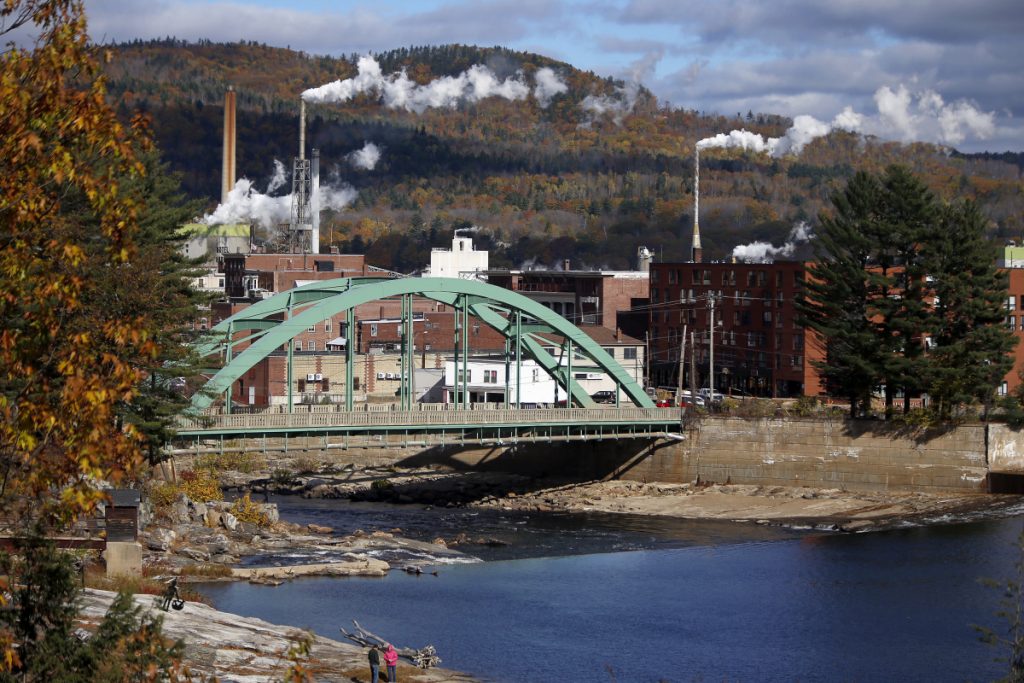

Rumford has been defined by its massive paper mill for several generations and it’s still the biggest presence in town. Traveling north on either side of the Androscoggin River, the steam from its stacks is visible first, followed by the distinct sulfuric scent.

Unlike some towns, the mill is still operating here, although it’s now on its third owner in less than five years and employs 600 people, about half what it did a decade ago. Anxiety remains about its future.

Linda-Jean Briggs, the town’s manager, said Rumford is trying to reinvent itself like any other mill town. She’s excited about the prospect of a new hotel, which would be the town’s first. She hopes it will bring even more interest in Black Mountain, a local ski and recreation area. Poland Spring is exploring the purchase of 100 acres that had once been set aside for an industrial park for a new bottling plant.

Among residents, though, there is still a feeling that the town’s fortunes are not on anyone’s minds outside Rumford. That sense of isolation seems to contribute to voter indifference, too.

Mary Ann Fournier, 28, works at the library part time but also has another job as registrar of voters. She’s passionate about voting but knows many in her age and peer group who couldn’t care less.

“It seems like the people I know need something to vote for or against,” she said, using same-sex marriage and marijuana legalization as examples. Candidates, Fournier said, don’t seem to draw as much interest.

Jodi Campbell used to feel that way. She didn’t vote, in fact had never even registered, until she was 32. That was 2008, the year Barack Obama was first elected.

“He sort of changed my mind about politics,” said Campbell, who works at the Deluxe Diner, a hole-in-the-wall on a quiet side street near downtown.

Campbell said she tries to vote in every election now.

Voter data shows that the older people get, the more likely they are to vote. People in their 60s or 70s will vote in any election, no matter what is on the ballot. Younger people, like Fournier said, often need a strong reason – something to vote for, or sometimes against. A polarizing or inspiring candidate.

Brewer said voting has to become habitual, and that takes time.

Maine has two things that make voting especially easy – absentee voting and same-day voter registration. That’s not true in other parts of the country.

But sometimes, voters avoid elections because they don’t feel like they know enough. Brewer recalled a scene recently when he was at the UMaine student union getting lunch. Three students passed by a table that had been set up to register voters. All three declined to stop. As they walked away, Brewer said, one of them asked another, “Are you going to vote?” and the woman replied, “Oh my God, no. I have no idea what’s going on.”

PARTISANSHIP INTENSIFYING

Rumford is one of the most heavily Democratic towns in the state in terms of registration. Democrats outnumber Republicans more than 2-to-1. But those numbers are misleading.

In the 2016 presidential election, Rumford was among the towns that saw the biggest swing from the 2012 election to 2016. Obama won Rumford 61-34. Four years later, Trump won the town by a 50-41 margin over Hillary Clinton.

This was true all over the country. Trump’s support was fortified in towns like Rumford, economically struggling communities of mostly white, mostly non-college-educated voters.

A lot of residents in these towns see the partisanship that has worsened since then as a turnoff.

Lou Marin, 46, said his biggest issue is with the two-party system, which has become increasingly tribal.

“If I say I’m a Republican, I have to believe in all these things automatically, but that’s not really how it works,” he said. The two parties are each drawn to power, Marin said, and he believes the old adage that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

“Everybody compromises their own morals, which means we don’t have any morals left,” he said of politicians.

The result, Marin said, is people voting on things that don’t matter. Whoever speaks the loudest gets the support. That doesn’t appeal to him.

Mark Moore, who lives in nearby Mexico, just across the river, said he doesn’t vote either. He said he can’t connect with politicians. They all seem like crooks.

“When I was a kid, it seems like John F. Kennedy was somebody who did good and he got killed,” said Moore, who is 58 and disabled.

Since then, he said, “I haven’t really found anyone I like.” Now, he doesn’t watch the news much. He’s not even sure who’s on the ballot this year.

‘THEY ARE ALL CROOKS’

But that lack of interest isn’t true of everyone who doesn’t plan to vote.

Walton, the trainer, pays close attention. He leans conservative, libertarian even, and follows issues closely. But he doesn’t feel like he’s at home with the Republican Party. He doesn’t think Trump is a conservative and has some colorful words for his governing style.

As an example of his independent streak, he said he would have voted for Bernie Sanders over Trump in 2016 because “at least Bernie believed in something. I didn’t agree with it, but I respected it.”

He said being political carries too much baggage. If he doesn’t vote, he doesn’t have to worry about defending or explaining his vote to anyone.

Currivan, the library worker, said he recently voted in June but that was for a specific reason. It was for the municipal budget that included, among other things, his salary at the library.

His co-worker, Fournier, the town voter registrar, keeps trying to convince him to take his vote more seriously. But Currivan said he doesn’t want to pay attention to what’s going on.

Maybe he’ll become a regular voter in the future. Maybe he’ll turn into Donny Ducas.

Ducas, a retired carpenter, said he hasn’t voted in 50 years. Not since Richard Nixon in 1968.

“I lost all faith after Nixon was caught and stepped down,” he said. “They are all crooks.”

It’s not that Ducas doesn’t see the value in voting. He thinks people should vote. He just can’t bring himself to do it.

“I guess I hold a grudge,” he said.

Comments are no longer available on this story