Good news for moose: The overall population is up, but the number of car-moose collisions is trending down.

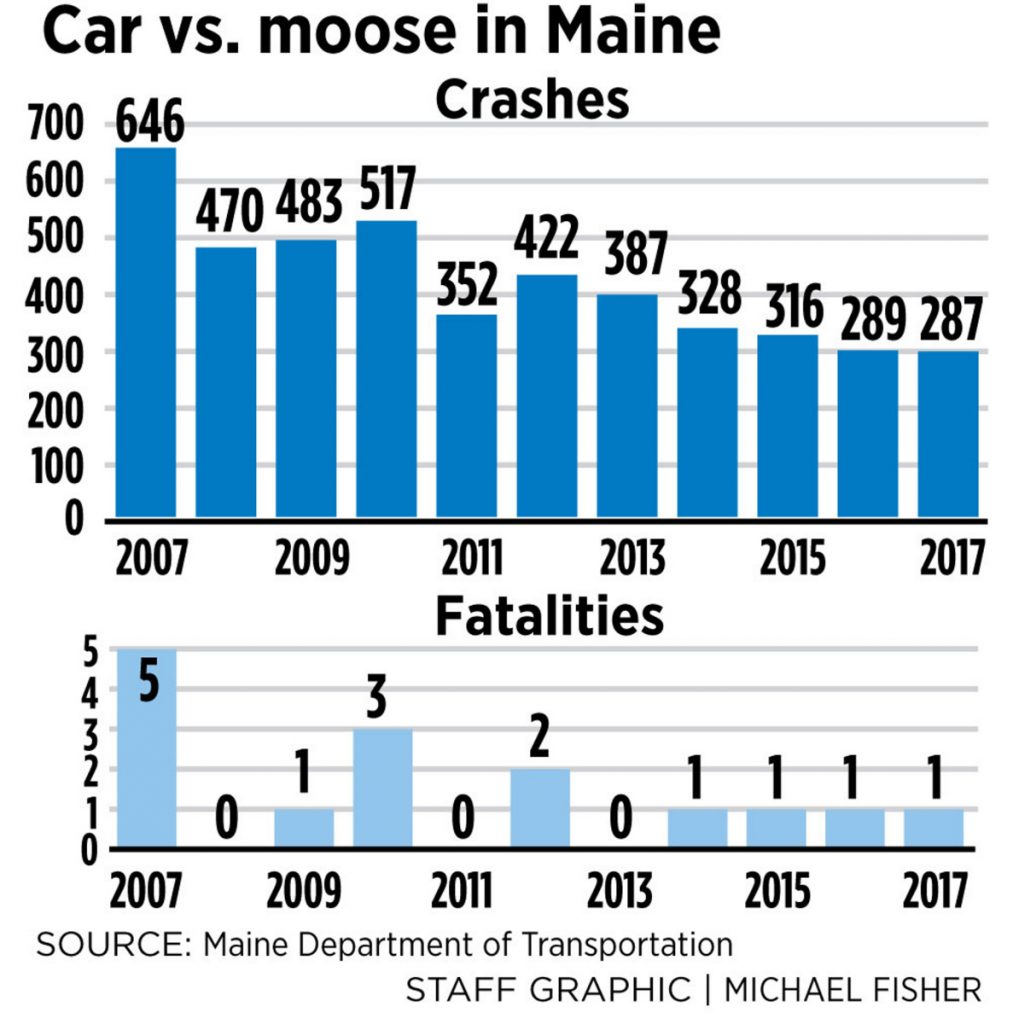

In 2017, there were 287 car crashes in Maine involving a moose, according to new data from the Maine Department of Transportation.

That’s less than half the 646 crashes 10 years earlier, in 2007, and down 32 percent from five years earlier, in 2012.

So far this year, there have been 158 car-moose crashes, continuing the downward trend.

But it can sure feel like an uptick when collisions are clustered in a certain place, one northern Maine lawmaker said.

“I’ve had six people just in my little circle that have hit one this summer,” said Sen. Troy Jackson, D-Allagash.

There are only about 250 people living in Allagash.

“There’s a stretch of highway (from lower Allagash) before you get to the main metropolis of Allagash that’s a 3- or 4-mile stretch. There have been four moose collisions in that little old stretch there just this summer,” Jackson said. “Which is really odd. We never used to see that there.”

Jackson had enough constituents complaining about moose collisions that he invited state officials up for a forum. Moose biologist Lee Kantar of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife walked them through some of the factors that guide moose behavior.

Kantar says long-term crash data indicate the number of collisions is down “significantly” over the last 15 to 20 years.

There isn’t a specific reason why that may be, he said, but there are certain things that are clearly factors. Visibility is a major factor – Maine DOT tracks how many accidents happen on a curve versus a straight road – and driver inattention.

Moose populations vary year by year, and probably aren’t a big factor, but there are some predictable reasons that explain why a moose is crossing the road.

Kantar said younger moose “tend to wander quite a bit” in the summer months – an idea borne out by data showing that most accidents happen in June.

A long-term study of collared moose that tracks their movements showed that some yearlings travel 100 miles over the course of just a few weeks, he said.

“Obviously in doing that, they’re going to be crossing roads,” he said.

There was one driver fatality last year, when a car hit a moose on Interstate 95 in the town of Howland in Penobscot County. Another 42 accidents caused some injury to drivers.

Because of the size of moose, any collision can be fatal or cause extensive damage. The Maine DOT website offers a list of tips for drivers, including the fact that while deer eyes will reflect headlights, moose are so tall, the eyes won’t be reflected in headlights, making them harder to see.

Moose, which travel in groups, are most active around dawn and dusk but also travel at night. In addition, drivers should note moose warning signs, which are located where there are known concentrations or a history of collisions.

And if a crash is unavoidable, officials say drivers can minimize the risk of driver injury by applying the brakes and steering straight, then letting up on the brakes just before impact to allow the front of the vehicle to rise slightly, and aiming to hit the tail end of the animal. That can reduce the risk of the moose striking the windshield and may increase the driver’s chance of missing the moose. Drivers should also duck to avoid windshield debris.

As in previous years, clusters of collisions happened along the I-95 corridor north of Bangor, Route 201 in Somerset County and along Route 11 and Route 1 in Aroostook County.

As for Jackson, he’s taking a practical approach to lower the risk of car versus moose. If re-elected, he’ll push for state funds to get the trees and grasses trimmed back from the highways.

“Ten or 15 feet on either side at least,” he said. “It gives you a chance to brake, instead of them just stepping right into your vehicle.”

Comments are no longer available on this story