In his first novel, “Hauling Through,” set in a midcoast lobstering community, Peter Bridgford gave us a lively story populated with colorful characters, most of whom would be readily recognizable to anyone who has spent time in a fishing village in Maine. In reviewing that book in these pages, I commented on the author’s pitch-perfect ear for dialogue and how it made the people, as well as Kestrel Cove itself, come alive on the page. I did, however, complain about one character’s constant need to make reference to the War Between the States.

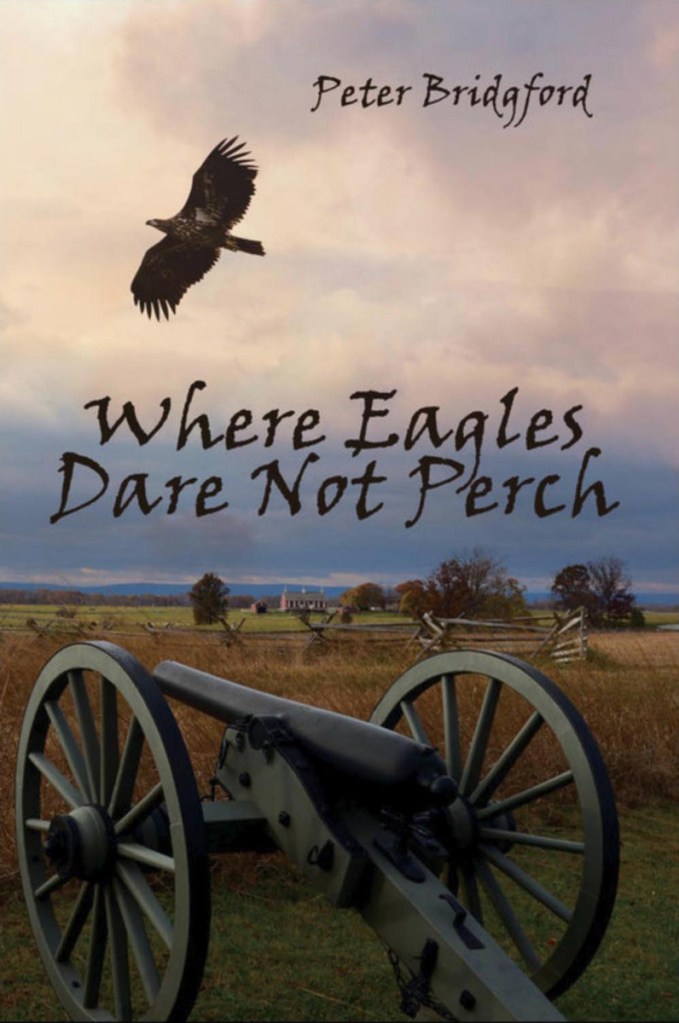

It’s a subject Bridgford knows a lot about, so it is not surprising that his second novel should take that calamity as its main theme. “Where Eagles Dare Not Perch” (the quote is from Shakespeare’s “Richard III”) is a very different book. To say that it is more like an ancient saga recognizes the grandness of its scope, but it also explains some of the story’s problems as a novel.

Actually, I am not at all sure that a novel (as we generally think of a novel) is what the author wished to write. It is more like a passion play, with outsized characters and a Homeric plot. The reader doesn’t get too far into the book before sensing that the story’s arc is that of a redemption myth, and probability be damned. For the most part, Bridgford carries it off with flying colors.

Readers are not likely to recognize any of the three protagonists. They are all severely damaged in their being. I cannot say psychologically damaged because they (two men and a woman) are resolutely pre-Freudian. To deal with unspeakable memories, a traumatized victim is told, “Lock them up and throw the key away so you’ll forget. You should never speak about it again!” Their creator has clearly dispensed with psychology altogether in favor of archetypes.

When we meet Zachary Webster, the Civil War has already turned him into a psychopath. His sweetheart, Catherine Brandford, is an innocent, if headstrong, young woman who is soon to be degraded. The third protagonist, Jedediah Stiller, is a tattoo-covered behemoth whom tragedy has turned from a gentle giant into a monster. When Zachary, on furlough from fighting for the Union, kills Jedediah’s younger brother for courting Catherine in his absence, the giant sets off to the war zone on a quest for a most unholy grail: to murder Zachary as painfully as possible. Realizing that it is her ill-considered actions that have set this train of events in motion, Catherine becomes a battlefield nurse and sets off after them.

Each is on their own pilgrimage, which quickly becomes a personal Calvary. Bridgford does not spare us much detail in the violence that is variously visited upon them. Their sufferings closely parallel each other. This is an epic where symmetry is more important than quotidian realism. Events pile on with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy.

Peter Bridgford

In the course of his tale, the author shows off some dazzling narrative technique. We see Zachary’s dehumanization through a remarkable series of conversations, one with Catherine, one with the corpse of his father (in the barn, waiting for the spring thaw to be buried), and one with some nosy neighbors who wish to be regaled with glorious deeds of valor. Another is the way Bridgford makes the reader’s feelings about Jedediah do a 180 and back as he becomes alternately pursuer and pursued.

Always looming over the personal tribulations is the juggernaut of the war, specifically the buildup to the bloody Battle of the Wilderness. Here Bridgford is in his element. The book is dedicated – as well as to his family – “to my former students at Breakwater School for encouraging me to turn one of my boring history lessons into an entire story and book.” I very much doubt they were boring.

Aside from his historical knowledge, Bridgford is a master of description, letting all our senses feel the “shouting men, creaking caisson axles, the constant snapping sounds of whips on oxen and mule teams, the hoofbeats of steeds bringing messages to and from headquarters.” His research never comes out as anything but a way to communicate a terrific story.

After all this, it is regrettable that the denouement is so unsatisfying. After having survived or inflicted violence ranging from rape, dismemberment and murder to cannibalism, the protagonists decide to forgive all and head West together. There was never any doubt that it would come to pass, but horrible acts have not been so lightly washed away since Candide finished his adventures by going off to cultivate his garden.

It’s a surprising and sad come-down for the story. But don’t let it stop you from enjoying the rest of “Where Eagles Dare Not Perch.”

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and the author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story