It’s hard to wrap your head around the idea that Dahlov Ipcar was still making art when she passed away last year, and that she had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939.

One of Maine’s best-known and best-loved artists, Ipcar (1917-2017) was the daughter of Marguerite and William Zorach, internationally prominent modernists perched near the top of the Maine pantheon. Ipcar also wrote and published 42 books, illustrating 34 of them herself, as well as many more for other authors.

While she grew up in the spotlight and found the stage early, Ipcar remains artistically evasive despite the ease with which anyone can recognize her images. Their pageantry blossoms with cartoon-like clarity, flat colors and solid-line drawing. They practically dance with the rhythms of boldly printed fabric. Her paintings, drawings, sculptures and prints, moreover, don’t seem to veer overly far from her illustrations. But Ipcar’s staying power resides less in what is easy to see in her work than in its depth and its propensity for looking at the dark edges of typically bright things.

Ipcar’s imagery is led by animals, knights, forests, jungles, moons and players from the age of chivalry. It’s easy to write off as fantasy for children, but Ipcar blends the logic of games with the irrationality of dreams, memory and the largely inaccessible mentalities of ourselves at much younger (and more idyllic) ages. Her sense of narrative is far more surreal than real. And she buries its engines like memories of an adult trying to recall what it was like to be child deep in fantasy play. There are no easy paths, no boundaries and certainly no platitudes.

Beautifully installed, “Blue Moons & Menageries” is smartly divided between the two levels of the Bates Museum of Art. Ipcar’s paintings are displayed on the main level, while her illustrations and prints fill the lower gallery. “Blue Moons” is particularly complete and remarkable because many of the works are now being exhibited publicly for the first time. We have seen some, most recently at Rachel Walls Fine Art in Cape Elizabeth, but many of the works are from private collections, including Ipcar’s own family. However well you think you know Ipcar, there is much you have never seen and may likely never have the chance to see again.

“Blue Moon Games,” 2006, oil on linen, 30 by 30 inches.

“Blue Moon Games” (2006), for example, is on loan courtesy of the Charles Ipcar family. It is part of the suite of “Blue Moon” paintings from which the exhibition takes its title, but this work also lays out the game and play logic that Ipcar follows to such artistic depth. This painting is a quilt-like, flat-patterned square field featuring game board systems: chess, backgammon and Chinese checkers (which, despite the name, is originally a German game called “Sternhalma”). Most notable about the choice of game boards is their geometrical orientation: Backgammon is linear but base six (the six units of each quadrant are based on the six sides of a die), Chinese checkers is hexagonal, and chess uses a 2D Euclidean “x, y” grid. The field is then filled with Ipcar’s regular players: zebras, rabbits, dogs, knights and a pair of women, one black and one white, who we imagine are the goddesses of night and day.

Stylistically, Ipcar is easy to spot. Yet her work is directly connected both to her parents’ thoroughly modernist painting and the more decorative branch of cubist tradition relating to artists such as Marc Chagall, Juan Gris and Georges Braque. The battle cry of the original cubism of Picasso and Braque could easily be said to be their breakdown of the word “journal” (French for “newspaper”) into “jour” (day) and “jou” (play) as it is partially seen in many paintings. Ipcar seems to have fully integrated this: She uses the newspaper logic of partitions as well as its flat (table) or upright (being read) orientation option. She takes the day/night distinction down a more dynamic yin-yang road. And then the idea of play fully activates her work in any medium.

It is with this idea of play that Ipcar’s work gets complex and almost strangely nuanced. She blends adult ideas about, say, history and systems. Adults play chess, for example, but they use fantasy terms like “queen” and “rook.” In “Ancient Battleground” (also a family picture), Ipcar shows a chess board in battle, and the rook (or “castle” to some) is an actual rookery with a crow flying from it to the battlefield. The knights ride horses and a pawn is accompanied by his dog.

Ipcar uses aspects of what we know about history, animals, our fragmentary understanding of exotic places such as rain forests or jungles. She blends our knowledge of games and storytelling with cognitive processes such as memory, fantasy and dreaming in uncanny and unresolved images akin to surrealism. But Ipcar, an accomplished chess player, will also deploy multiple systems strategically, or even allow the owner of a piece to make such a choice.

“Pastures of Memory,” 1962, oil on linen.

One of the “Blue Moon” suite, for example, is owned by a woman who prefers animals to people and so hangs the work at an angle with animals on top rather than the deities of night and day. And yes, Ipcar, often signs her work in multiple places at angles to play up this option: Some of the works are intended to be hung at any of eight directions.

This too relates to game board logic: Game boards are flat and intended to be seen from many angles.

Ipcar’s work, however, is also deeply personal and she works to convey a subjective experience to the individual viewer. “Pastures of Memory,” for example, is a field of flora and fauna transforming in and out of each other. But in the upper right quadrant is a small girl in a red top. Presumably, she is sitting in the pasture and what we are seeing are her fantasies, thoughts, memories and dreams about the experience. It could be autobiographical, but Ipcar lets us identify with the figure or see it as we choose.

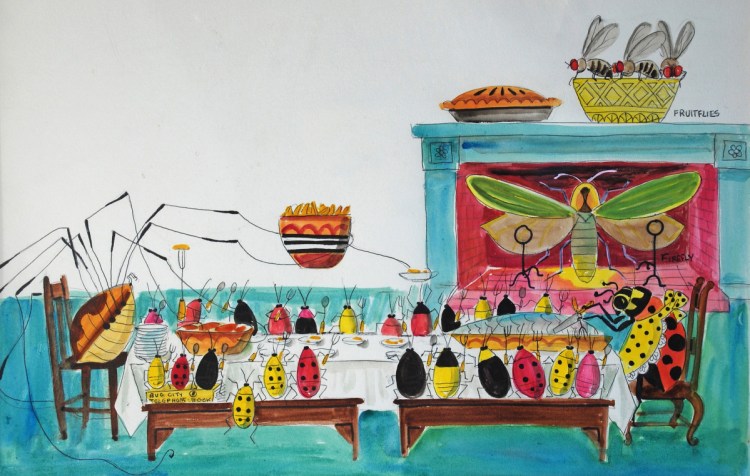

Ipcar’s books and illustrations comprise a large proportion of her reputation and output. For the most part, these match the complexity of the paintings and often go further in pressing a bit of darkness into the scene. Some are intentionally witty, such as her bug pictures with Daddy Long Legs at the head of his family table or the sweeping of a carpet beetle. Others are sweet, such as the pictorial ballad of Froggie, who successfully courted Ms. Mouse. Some are terrifying, such as the image of the sea monster, a giant squid whose legs appear as a swarm of snakes in a roiling ocean. Others still are merely dark: a cat at night by the road, a boy who catches ever larger and more terrifying fish, and so on.

But as we know from the Brothers Grimm, children’s stories often find power in their confrontations with dark forces. Ipcar is comfortable showing us cats on tables, game play or dreamed scenes of jungles. Within all of her works, however, is a sense of conflict. Sometimes, the conflict is between dreams and reality. At other times, it’s between opponents, or day/night, people/monsters, history/fantasy and so on. Her ability to draw from so many realms of memory, knowledge, fantasy and dreams is what makes Ipcar a unique narrative artist who accomplishments may never be matched again.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story